Modal elements denoting emotion in minoritized languages. Educational personalization strategies, resources and experiences

4.2. MODAL ELEMENTS TO TRANSMIT EMOTION IN MINORITARIAN LANGUAGES. STRATEGIES, RESOURCES, AND EDUCATIONAL PERSONALIZED EXPERIENCES

It is necessary to encourage initiatives that allow is to give emotional resources to face situations where there is a backing down or a cognitive dissonance. Contexts in which not speaking Valencian does not ease communication and, furthermore, generates frustration and harms the self-esteem (Suay i Sanginés 2010).

Social networks are key to create an affection and solidarity connection towards the language. Speakers with a higher degree of commitment and availability can apply it through formulas, such as linguistic voluntary work, support in conversation groups or linguistic tandems. It is not necessary to be a member of a collective or association devoted to the language in order

Information extracted from Nicolás Amorós, M. (2019). Del conflicte lingüístic valencià als consensos del multilingüisme “autocentrat”. València: Universitat de València. Càtedra de Drets Lingüístics. (Quaderns d’Estudi). Online: https://www.uv.es/cadrelin/quartllibre.pdf

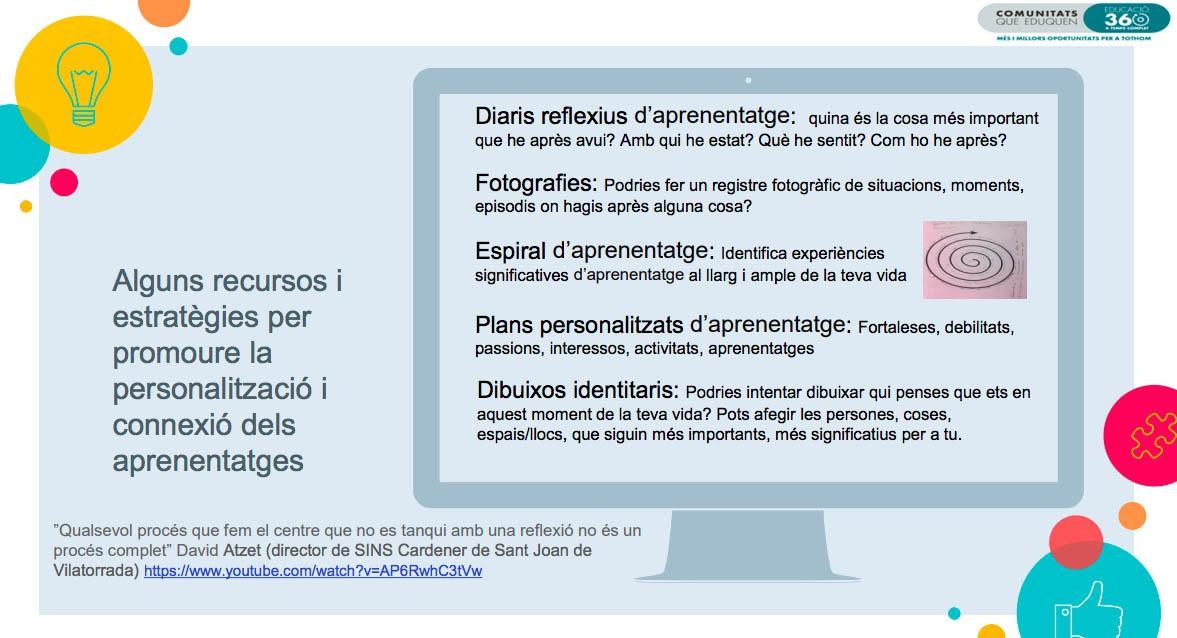

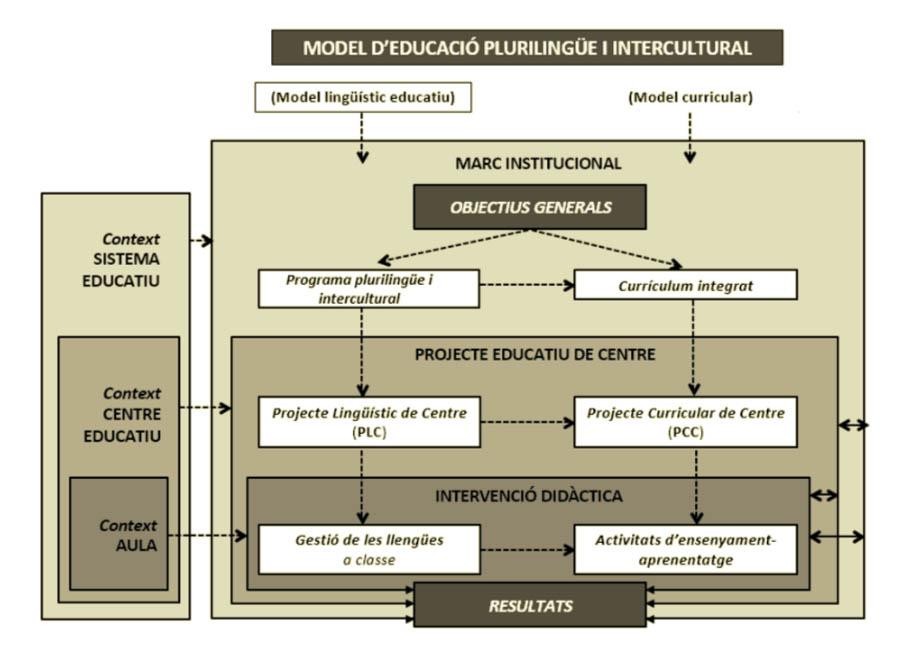

In the last decades, there have been significant changes in the parameters linked to learning: where, when, how, with whom and what we learn. These changes define a “a new learning ecology”, that is radically different to the one previously present in schools, and hence presents challenges and opportunities that require different educational actions, policies and practices. Customized learning contributes to the identarian construction process, since it helps the children to better understand who they are and offers them tools to understand the past, the current conditions, and the generation of future expectations and actions. Therefore, customization is defined by a series of resources, diversified and heterogeneous strategies aimed towards allowing the learner to find a sense and a personal value in everything they learn.

We consider significant learning experiences the situations, practices or activities where the learner admits having learnt something and, furthermore, because they have impact, either positive or negative, they are organized hierarchically as particularly relevant, important and valuable.

It is necessary to find an agreement shared by all the agents, as well as the participation of the learner, which makes it easier for them to be involved. Therefore, for example, it is necessary to diversify school educational projects and activities, co-developed with territorial entities ,to offer the learner’s options to develop customized learning plans depending on the particular learning concerns, the needs, the interests, and the objectives.

It is therefore essential to offer children and youngsters the space and time to connect learning experiences ,to co-identify and co-create interests, to link them with the educational contexts, resources, and opportunity, which include actions shared between different educational bodies and agents within the community. The final goal is, hence, to connect educational agents spaces and times in a local educational ecosystem understood as a customized educational space.

Text Extracted from Esteban-Guitart, M. (2020) La personalització de l’aprenentatge: itineraris que connecten escola i comunitat. Educació 360.

Image extracted from Esteban-Guitart , M. (2018). Personalització de l’aprenentatge. Universitat de Girona.

PROPOSALS, IDEAS AND SUGGESTIONS TO RESPECT LANGUAGES

The first fundamental step, without which all other steps will be wrong, is the respect to all languages. The idea that all languages are the same, that there are no languages that are better than others, that there are no primitive or word-lacking languages, that there are no uneducated languages. This is something we should all understand. Turning our back to this reality is in the origins of many negations and concealments of the own language. If we do not have a more open-minded approach towards linguistic diversity, a respectful, interested approach, that appreciates this wealth and does not consider it a problem, it will be difficult to achieve anything. School, that is, a key part of our education, has, as usual, a lot to say about this. It is necessary to train teachers specifically and combatively against linguistic prejudices.

We must also propose a new linguistic order that overrides the identification of language and State, and whose main goal is building a world where diversity is possible. Often, linguistic planning is only a crazy race towards hegemony, meaning a suppression of all “rival” languages. We need to design a plan that guarantees survival without oppressing the others.

Extracted from Comellas, P. [et al.]. (2014). Què hem de fer amb les llengües de la immigració a l’escola? Un estudi de representacions lingüístiques a l’Anoia. Horsori.

WHY IS IT KEY TO EDUCATE IN THE NATIVE LANGUAGE?

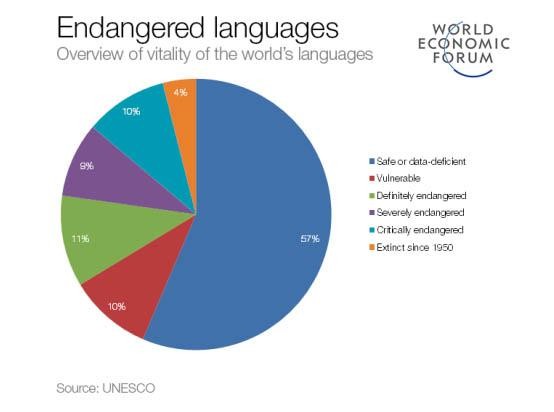

Languages, with their complex links to communication, identity, social integration and education, are strategic factors for the development of societies. Nevertheless, languages are increasingly endangered. In some cases, some are completely disappearing. When a language dies, not only does it disappear as a language, but also as a means to interpret the world and, therefore, all of humanity suffers a loss. According to UNESCO, there are currently around 3000 languages that are endangered and their destruction implies also a decrease of the rich world-wide cultural diversity network. It means the loss of countless traditions, memories, thought systems ,expressions, and many valuable resources that are necessary for a wealthier future.

Research shows that educating in the native language is a key factor for inclusion and quality learning, and that it also improved the learning and performance results. Every initiative towards promoting native languages implies not only a promotion of diversity and intercultural dialogue, but also a strengthening of cooperation, of knowledge societies that are integrative, and of the preservation of the cultural material and immaterial heritage.

According to United Nations, it is likely that more than 50% of the almost 7000 languages spoken in the world disappear in only a couple generations, and 96% of them are spoken by 4% of the population. Only a couple hundred languages have had the privilege to be included in educational systems and in the public domain, and less than a hundred are used in the digital world.

Text adapted from UNESCO (2022). “Why is mother language-based education essential”. International Mother Language Day.

Image extracted from Lingkon Serao/Shutterstock.com

BELIEFS SORROUNDING THE LEARNING-TEACHING OF LANGUAGES

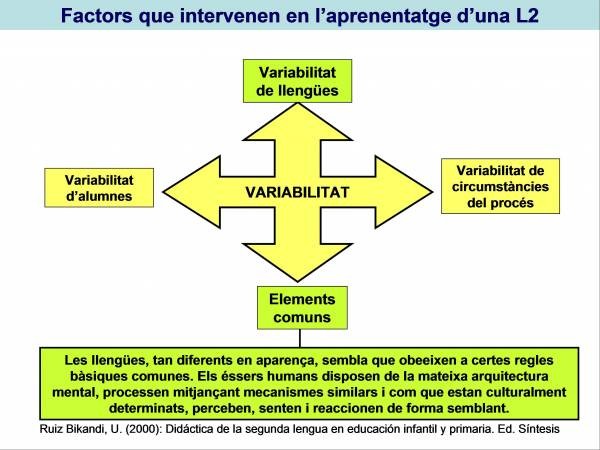

As Ruiz Bikandi (2000) states, the acquisition of an L2 can mean the acquisition of a second identity, the learning of a new culture, which might trigger that the own identity struggles and fears disappearing. On the other hand, certain elements, such as self-esteem, extroversion or introversion, anxiety degree, empathy or risk capacity affect the learning process. It seems obvious that linguistic acquisition and some attitudinal factors feedback on one another.

Research regarding language learning confirm that the motivation and the emotional factors are key. According to Guasch, Milián and Ribas (2006) it is convenient to consider the diversity of the expectations of an heterogeneous student body and their belief system in order to make progress in a more effective educational practice. Garcia Vidal (2018) points out that the learning process among students depends greatly on their motivation and personal abilities. The classroom is a space where we find students with very heterogeneous profiles and with a wide variety of learning styles. It is advisable to take multiple intelligences, affective education, attention to diversity, and individuality into consideration in order to i

Information extracted from Garcia Vidal, P. (2018). Com s’aprenen les llengües en Secundària. Perifèric.

LINGUISTIC AND SOCIOLINGUSITIC REFLECTION

Another task that allows for reflection are linguistic biographies or linguistic life stories. As Palou and Fons (2010: 260) explain: “Teachers can create contexts that allow promote reflection on the own linguistic repertoire. This metalinguistic and metacultural reflection can help to realize the potential that linguistic diversity always entails.”

Linguistic and sociolinguistic reflection is necessary to revert attitudes: raising awareness, the comprehension of the country’s sociolinguistic situation and the linguistic consequences that it has, exposing linguistic prejudices, etc. In this sense, it is convenient to combine a dose (not excessive) of objective and questioning information with a reflection on real or induced experiences.

Information extracted from Vila, F. X. Boix-Fuster, E. (eds.). (2019). La promoció de l’ús de la llengua des del sistema educatiu: realitats i possibilitats.UB.

LINGUISTIC USES IN MINORIZATION CONTEXTS

All communicational situation is a source of stress for humans (Sapolsky 2004), especially for the speakers of a minority language, who must face situations of linguistic uncertainty with each new social interaction (Suay i Sanginés, 2010). While speakers of dominant languages (DL) use their languages comfortably in every social situation and with all kinds of partners, the speakers of minority languages (ML) live in a completely different situation. We can differentiate three main categories of ML speakers depending on how they exert linguistic submission when they talk to a DL speaker:

a) Proactive: the start their interactions directly in the DL and only use their language when their partner has said that they are a speaker of this language;

b) Reactive: thy start speaking in the ML, and change to the DL when their partner identifies as a speaker;

and c) Resistant: they insist on speaking the DL, even if the speaker is not. It is not necessary to say that these behaviors have an origin and historical causes that have generated them and that admit well-founded psychological explanations.

In order to counteract the negative impact created by the well-known convergence rule of the dominant language, Suay (2019) proposes the Catalan Conservation Rule (CCR) defined as the attitude to continue speaking Catalan with everyone who is capable of understanding it. It is true that understanding a language is not always straightforward. As a matter of fact, one of the mains strengths of the imposition of Spanish or French in Catalan-speaking areas has been, and still is, the existing of monolingual speakers (in Spanish or French), who insist that they do not speak, or even understand, Catalan. Ignorance is hence difficult to counteract, and places the pressure on the minoritarian speaker, who is, in this case, the most capable, that is to say, the less ignorant one. Systematically speaking in Catalan, as long as communication is possible, is what we, as individual speakers, can do in order to contribute, partially regardless of the political situation of the moment, to the language’s well-being.

Information extracted from Suay, F. (2019). Com incidir sobre els usos lingüístics? Una perspectiva psicològica. En Vila, F. X. Boix-Fuster, E. (eds.) La promoció de l’ús de la llengua des del sistema educatiu: realitats i possibilitats.UB.

LINGUISTIC AND DIALECTAL DIGLOSSIA. LINGUISTIC DISCRIMINATION

The first one to define diglossia was the linguist A. Ferguson (1959), referring to a language and its variants. In this case, we call internal diglossia: “[…]a relatively stable linguistic situation where, beyond the dialects of a language, there is an extremely divergent superimposed variety, very standardized, used in literature and in school, but where no one uses the language in normal conversation.”

Later, sociolinguist J. Fishman applied the different use of languages in the same linguistic community. A language is used in formal and standard functions. This is what we call the prestige language, known as language A. The other language, the speaker’s own, is used in informal situations and is called language B. In this case, we use the term external diglossia.

If in a situation of contact languages there is diglossia, that is, if there is a hierarchy and non-majoritarian languages are displaced, many minoritarian languages (with few speakers) can become minority languages (the number of speakers is reduced further). However, people tend to increasingly acquired plurilingual competences and the societies have, as well, a population that is increasingly diverse and with multilingual communicative practices. In order to guarantee for all speakers that capacity to combine the knowledge and use of different languages there should be a justice-based plurilingualism.

Now, institutionally-based international actions in this sense are extremely weak as far as advancing towards equitable plurilingualism is concerned. Not even the realization that 90% of the world languages can disappear this century has made people aware of the urgent need to act at a major scale to avoid it. Some possible actions that could be taken are:

-

establish a constitutional frame that acknowledges linguistic diversity as a valuable human capital that multiplies relationship options, both in the cultural and the economical fields, and contributes to social cohesion;

-

acknowledge diversity and fight against inequality;

-

promote the knowledge of languages recently arrived to a territory regarding the cultural or economic links with the rest of the world;

-

develop plurilingual and intercultural competence;

-

maintain an open interlinguistic perspective: adaptation of loans and development of the linguistic creativity skills.

We can see this in dissemination and information campaigns for linguistic equality in posters or videos, such as “Linguistic equality is …” from the Linguistic Policy Service in the Universitat de València.

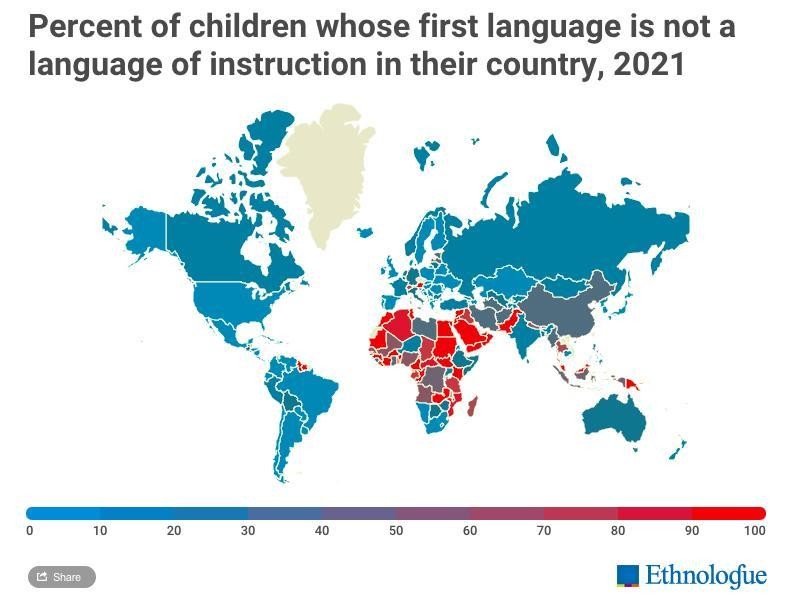

Just as there are no reasons to discriminate human beings, there are no reasons to discriminate languages. Even if the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights states that «Everyone is entitled to receive an education in the language proper to the territory where he/she resides» (Article 29/1), the data in the Ethnologue show that 35% of the children in the world start their education in a language they are not familiar with.

L

“Valencian-speakers are increasingly devoted to reporting attacks on their language.”

Natxo Badenes, president of Escola Valenciana, in an interview in Les notícies del matí in À punt (lValencian regional TV) (3-12-2021)

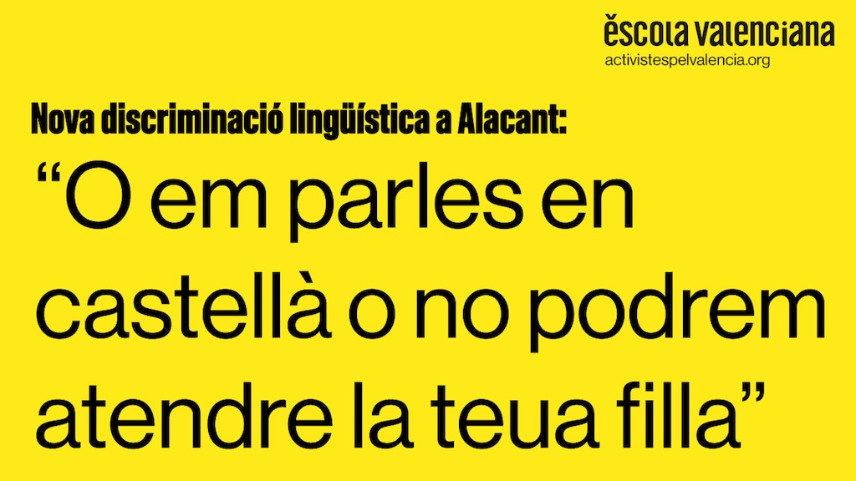

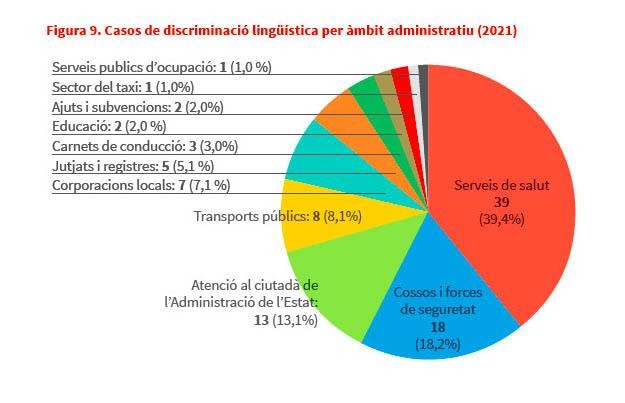

On the other hand, linguistic discrimination cases are frequent. The institution Escola Valenciana has reported many of these cases, like a family who complained about the treatment they received by a clerk in a health center in Alicante, who refused to engage with them unless they spoke in Castilian.

Image extracted from the news: Escola Valenciana denuncia una nova discriminació lingüística a Alacant: «O em parles en castellà o no podrem atendre la teua filla» (Vilaweb, 25-9-22)

This family explains the “absolute vulnerability” that they felt, when the worker snapped at them “If you don’t speak to me in Spanish, we cannot treat your daughter.” Furthermore, they say “it is not acceptable that you have to choose between having your daughter treated or expressing yourself in your native language.” Escola Valenciana points out that this is not an isolated case. The health system suffers an alarming situation, since it accumulates 1 out of every 3 reports to their Linguistic Rights Office.

Escola Valenciana offers their resources to every person who needs them, so that no linguistic breach remains unanswered, and informs that, when there is a complaint, like in this case, the institution will report to the Ombudsman, the Linguistic Rights Office of the Generalitat and the relevant institution, in this case, the Ministry of Health.

In the linguistic section in the journals La Veu, ARA and Vilaweb you can find more examples of reports.

Chart extracted from Tena, V. (2022): Discriminacions lingüístiques de rècord. El Temps.

VULNERABLE LANGUAGES

Diversity is frequently considered a problem. Most languages in the world are very vulnerable nowadays. An important portion of them will disappear during the next few decades, but this is no spontaneous process. It is due to a uniformization process that causes suffering, and that is a symptom of the propension towards domination and exclusion, and the lack of ability to cohabit with diversity.

T

Text extracted from Comellas Casanova, P.2021 «Llengües vulnerables: la diversitat lingüística en perill». Compàs d’amalgama, Núm. 4, p. 44-48. https://raco.cat/index.php/compas/article/view/392781

4.2. ELEMENTS MODALITZADORS QUE DENOTEN EMOCIÓ A LES LLENGÜES MINORITZADES. ESTRATÈGIES, RECURSOS I EXPERIÈNCIES DE PERSONALITZACIÓ EDUCATIVA

Caldria potenciar aquelles iniciatives que ens poden fornir recursos emocionals per a fer front a les situacions de claudicació o dissonància cognitiva. Contextos en què deixar de parlar valencià no facilita la comunicació i a més provoca frustració i lesiona l’autoestima (Suay i Sanginés 2010).

Les xarxes de relació social són bàsiques per a crear una trama d’afecció i solidaritat envers la llengua. Els parlants amb més grau de compromís i disponibilitat poden aplicar-hi per mitjà de fórmules com el voluntariat lingüístic, el suport als grups de conversa o els tàndems lingüístics. Però no cal formar part de cap col·lectiu o associació que faça explícita l’adhesió a la llengua per a contribuir-hi d’una manera o altra. La clau es troba en la voluntat i en la capacitat de participar en el canvi d’actituds. En efecte, es tracta de contribuir positivament a l’erradicació dels prejudicis que impedeixen avançar en l’ús del valencià. En les dècades centrals del segle passat, Kurt Lewin, un psicòleg alemany radicat als Estats Units a causa de la persecució nazi, va posar les bases de la psicologia social científica. Lewin va estudiar els requisits i les fases que regulen el canvi d’actituds en els grups socials. Partia de la premissa que només es podia comprendre bé una realitat social si es pretenia canviar-la. Així va diferenciar tres estadis en tot procés de canvi. En el primer, que ell anomenava de descongelació, calia desmantellar les creences i les pràctiques que es consideraven inadequades. Era l’estadi més ardu, atés l’arrelament dels hàbits quotidians. En un segon estadi, les certituds del vell sistema s’enfonsaven, cosa que creava malestar i confusió. El tercer estadi s’encetava quan començaven a cristal·litzar noves conviccions i pautes de conducta. Lewin en deia recongelació i comportava un aprenentatge dolorós, per tal com calia interioritzar i reestructurar pensaments, actituds, emocions i percepcions nous, que substituïen els caducs. L’observació de Lewin tenia una utilitat pràctica. Els Estats Units havien entrat en guerra contra les potències feixistes. A la reraguarda, les dones es van incorporar de manera molt activa a l’esforç bèl·lic. Lewin va observar que les dones s’hi implicaven molt més quan participaven en grups de discussió que debatien sobre les noves directrius i valors que volia impulsar el govern. Si només rebien instruccions, encara que fos en xarrades formals divulgatives, els resultats no eren tan bons. Calia que s’hi implicassen, que mirassen d’experimentar les novetats i de compartir informació entre elles.

Informació extreta de Nicolás Amorós, M. (2019). Del conflicte lingüístic valencià als consensos del multilingüisme “autocentrat”. València: Universitat de València. Càtedra de Drets Lingüístics. (Quaderns d’Estudi). En línia: https://www.uv.es/cadrelin/quartllibre.pdf

LA PERSONALITZACIÓ DE L’APRENENTATGE

En les últimes dècades hi ha hagut canvis significatius en els paràmetres vinculats a l’aprenentatge: on, quan, com, amb qui i què aprenem. Aquests canvis caracteritzen una “nova ecologia de l’aprenentatge” radicalment diferent de la que va sostenir l’educació escolar i planteja reptes i oportunitats que requereixen actuacions, polítiques i pràctiques educatives diferents. La personalització educativa contribueix al procés de construcció identitària, en la mesura que ajuda a l’infant a entendre millor qui és i l’ofereix pautes de comprensió del passat, de les condicions presents, així com la generació d’expectatives i actuacions futures. En definitiva, la personalització es caracteritza per un conjunt de recursos, estratègies, oportunitats diversificades i heterogènies encaminades a que l’aprenent pugui donar sentit i valor personal a allò que aprèn.

S’entén per experiències significatives d’aprenentatge aquelles situacions, pràctiques o activitats on l’aprenent reconeix haver après alguna cosa i, a més, pel seu impacte, sigui positiu o negatiu, les jerarquitza com a especialment rellevants, importants, valuoses.

És necessari que hi hagi compromís compartit dels diferents agents, així com participació de l’aprenent, la qual cosa facilita la seva implicació. Així doncs, per exemple, s’ha de diversificar els projectes i activitats educatives escolars, co-realitzades amb entitats del territori, per oferir a l’aprenent possibilitats de desenvolupar plans personalitzats d’aprenentatge en funció de les inquietuds, necessitats, interessos i objectius d’aprenentatge particulars.

Per tant, és imprescindible oferir als infants i joves espais i temps per connectar les experiències d’aprenentatge, per co-identificar i co-crear interessos, per vincular-los amb contextos, recursos i oportunitats educatives que incorporin actuacions compartides entre diferents entitats i agents educatius de la comunitat. En definitiva, per connectar agents, espais i temps educatius en un ecosistema educatiu local, en tant que espai de personalització educativa.

Text extret d’Esteban-Guitart, M. (2020) La personalització de l’aprenentatge: itineraris que connecten escola i comunitat. Educació 360.

Imatge extreta d’Esteban-Guitart , M. (2018). Personalització de l’aprenentatge. Univesitat de Girona.

PROPOSTES, IDEES, SUGGERIMENTS PER RESPECTAR LES LLENGÜES

El primer pas, l’imprescindible, aquell sense el qual tots els altres es donaran en fals, és el respecte per totes les llengües. La idea que totes les llengües són iguals, que no hi ha llengües millors que d’altres, que no hi ha llengües primitives i/o mancades de paraules, que no hi ha llengües d’incultura. Aquesta idea tots l’hauríem de tenir interioritzada. Perquè el desconeixement d’aquesta realitat és a l’origen de moltes negacions, de moltes ocultacions de la pròpia llengua. Sense una mirada més oberta cap a la diversitat lingüística, una mirada respectuosa, interessada, que valori aquesta riquesa i no pas que la consideri un problema, serà difícil arribar enlloc. I l’escola, és a dir, una part substancial de l’educació que rebem, hi té, com sempre, molt a dir. És per això que cal una formació del professorat explícitament combativa contra els prejudicis lingüístics.

I cal també proposar un nou ordre lingüístic que superi la identificació de llengua i estat i que tingui com a objectiu central la construcció d’un món on sigui possible la diversitat. Sovint la planificació lingüística no ha estat res més que una mena de cursa frenètica cap a l’hegemonia, una hegemonia que pressuposava l’eliminació de totes les llengües “adversàries”. Ens cal inventar una planificació que garanteixi la pervivència sense esclafar els altres.

Extret de Comellas, P. [et al.]. (2014). Què hem de fer amb les llengües de la immigració a l’escola? Un estudi de representacions lingüístiques a l’Anoia. Horsori.

PER QUÈ L’EDUCACIÓ EN LA LLENGUA MATERNA ÉS ESSENCIAL?

Els idiomes, amb la seua complexa imbricació amb la comunicació, la identitat, la integració social i l’educació, són factors d’importància estratègica per al desenvolupament de totes les societats. No obstant això, pesa sobre les llengües una amenaça cada vegada més gran. En certs casos, algunes estan desapareixent completament. Quan una llengua mor, no sols desapareix un idioma, sinó també una manera d’interpretar el món, i conseqüentment, tota la humanitat n’ix perjudicada. Segons la UNESCO, en l’actualitat hi ha aproximadament 3000 llengües en perill de desaparició i amb aquesta destrucció minva també la rica xarxa mundial de diversitat cultural. D’aquesta manera es perden nombroses tradicions, records, modalitats de pensament, d’expressió i molts recursos valuosos que són necessaris per a aconseguir un futur més ric.

Les investigacions demostren que l’educació en la llengua materna és un factor clau per a la inclusió i un aprenentatge de qualitat, i que també millora els resultats de l’aprenentatge i el rendiment escolar. Tota iniciativa de promoure la difusió de les llengües maternes serveix no només per a impulsar la diversitat i el diàleg intercultural, sinó també per a enfortir la cooperació, la construcció de societats del coneixement integradores i la preservació del patrimoni cultural material i immaterial.

Segons les Nacions Unides és probable que més del 50% dels quasi 7000 idiomes que es parlen en el món desapareguen en unes poques generacions i el 96% d’aquests són la llengua parlada del 4% de la població mundial. Només uns pocs centenars d’idiomes han tingut el privilegi d’incorporar-se als sistemes educatius i al domini públic, i menys d’un centenar s’utilitzen en el món digital.

Text adaptat de UNESCO (2022). “Por qué la educación en la lengua materna es esencial”. Dia Internacional de la lengua materna.

Imatge extreta de Lingkon Serao/Shutterstock.com

CREENCES SOBRE L’ENSENYAMENT-APRENENTATGE DE LLENGÜES

Tal com afirma Ruiz Bikandi (2000), l’adquisició d’una L2 pot significar d’adquisició d’una segona identitat, aprendre una nova cultura, per la qual cosa la pròpia identitat pot sentir-se angoixada i amb por de desaparéixer. D’altra banda, aspectes com l’autoestima, extraversió o introversió, el grau d’ansietat, l’empatia i la capacitat d’assumir riscos influeixen en l’aprenentatge. Sembla evident que el domini lingüístic i alguns factors actitudinals es retroalimenten.

Els estudis sobre l’aprenentatge de llengües confirmen que la motivació i els factors afectius són fonamentals. Segons Guasch, Milián i Ribas (2006) és convenient tenir en compte la diversitat d’expectatives d’un alumnat heterogeni i les seues creences per avançar en una pràctica educativa més efectiva. Garcia Vidal ((2018) remarca que l’aprenentatge de l’alumnat depén en gran manera de la motivació i l’aptitud personal. L’aula és un espai on podem trobar estudiants amb perfils bastant heterogenis i amb una gran diversitat d’estils d’aprenentatge. La consideració de les intel·ligències múltiples, l’educació emocional, l’atenció a la diversitat i individualitzada és, per tant, recomanada per a millorar l’aprenentatge.

Informació extreta de Garcia Vidal, P. (2018). Com s’aprenen les llengües en Secundària. Perifèric.

TASQUES DE REFLEXIÓ LINGÜÍSTICA I SOCIOLINGÜÍSTICA

Els alumnes més conscienciats són els més insegurs des del punt de vista lingüístic. Resulta molt rellevant reflexionar sobre les raons d’aquesta inseguretat, analitzar els comentaris en què es manifesta o els prejudicis que amaga. Per aquest motiu, es proposen tasques que desperten la crítica i que, posteriorment, en permeten una aplicació pràctica i real. Per acabar, amb l’excusa de fer una fotografia sociolingüística del barri d’on són o on viuen els alumnes, hauran d’elaborar un estudi de caràcter sociolingüístic que inclourà una entrevista quantitativa i una altra de qualitativa realitzada a alguns individus triats a l’atzar (centres, comerços, vianants). L’entrevista donarà dades relacionades amb les variables considerades (edat, relació amb les llengües, usos declarats, actitud, etc.), però també els farà experimentar les reaccions dels entrevistats davant un desconegut que s’hi adreça en català.

Una altra eina que permet la reflexió són les biografies lingüístiques o relats de vida lingüística. Com expliquen Palou i Fons (2010: 260): “Els docents poden crear contextos en els quals es promogui la reflexió sobre el repertori lingüístic propi. Aquesta reflexió metalingüística i metacultural pot ajudar a prendre consciència del potencial que sempre comporta la diversitat lingüística. “

La reflexió lingüística i sociolingüística és necessària per a revertir actituds: la conscienciació, la comprensió de la situació sociolingüística del país i les conseqüències lingüístiques que açò té, el desemmascarament de prejudicis lingüístics, etc. En aquest sentit, convé que es combine una dosi (no excessiva) d’informació objectiva i crítica amb la reflexió feta sobre experiències reals o induïdes.

Informació extreta de Vila, F. X. Boix-Fuster, E. (eds.). (2019). La promoció de l’ús de la llengua des del sistema educatiu: realitats i possibilitats.UB.

USOS LINGÜÍSTICS EN CONDICIONS DE MINORITZACIÓ

Tota situació comunicativa és una font d’estrès per als humans (Sapolsky 2004), i ho és, d’una manera especial, per als parlants d’una llengua minorada, que afronten situacions d’incertesa lingüística en cada nova interacció social (Suay i Sanginés, 2010). Mentre que els parlants de llengües dominants (LD) solen usar amb total comoditat els seus idiomes en qualsevol situació social i amb tot tipus d’interlocutors, els parlants de llengües minoritzades (LM) viuen una situació molt diferent. Es poden distingir tres grans categories de parlants de LM en funció de com exerceixen la submissió lingüística quan es troben davant d’un parlant de LD:

a) Proactius: directament inicien les seues interaccions en la LD, i només usen el seu idioma quan l’interlocutor s’ha identificat com a parlant d’aquest idioma;

b) Reactius: inicien en la LM, i canvien a la LD quan l’interlocutor s’identifica com a parlant d’aquesta;

i c) Resistents: s’esforcen per seguir parlant en la LD, malgrat que l’interlocutor no en siga parlant. No cal dir que aquestes conductes tenen uns orígens i unes causes històriques, que les han generades, i que admeten explicacions psicològiques ben fonamentades.

Per tal de contrarestar l’impacte negatiu exercit per la coneguda norma de convergència a la llengua dominant, Suay (2019) proposa la norma de manteniment del català (NMC) definida com l’actitud de continuar parlant en català amb tot aquell que estiga capacitat per a entendre’ns. És cert que això d’entendre un idioma no és sempre una qüestió diàfana. De fet, una de les fortaleses més importants de la imposició de l’espanyol o el francés als territoris de llengua catalana ha estat, i és, el manteniment de bosses de parlants monolingües (en espanyol o en francés), que sempre poden al·legar ignorància del català, i fins i tot incomprensió. La ignorància es converteix així en una força difícil de contrarestar, que col·loca tota la pressió sobre el parlant minorat, que és, dels dos, el més capacitat, és a dir, el menys ignorant. Parlar sistemàticament en català, mentre la comunicació és possible, és allò que els parlants individuals podem fer per tal de contribuir, amb una certa independència de la situació política del moment, al benestar de la llengua.

Informació extreta de Suay, F. (2019). Com incidir sobre els usos lingüístics? Una perspectiva psicològica. En Vila, F. X. Boix-Fuster, E. (eds.) La promoció de l’ús de la llengua des del sistema educatiu: realitats i possibilitats.UB.

DIGLÒSSIA LINGÜÍSTICA I DIALECTAL. LA DISCRIMINACIÓ LINGÜÍSTICA

El primer a definir la diglòssia fou el lingüista A. Ferguson (1959) i va referir-se a l’ús d’una llengua i les seves variants. En aquest cas, s’anomena diglòssia interna: “[…] situació lingüística relativament estable en què, a més dels dialectes d’una llengua, hi ha una varietat superposada molt divergent, molt estandarditzada, utilitzada en la literatura i l’escola, però que ningú no empra com a llengua de conversa ordinària”.

Més tard, el sociolingüista J. Fishman l’aplica al diferent ús de les llengües en una mateixa comunitat lingüística. Una llengua és usada per a funcions formals i estàndard; aquesta és la llengua de prestigi anomenada llengua A (alta). L’altra llengua, la pròpia, es fa servir en situacions informals i s’anomena llengua B (baixa). En aquest cas parlem de diglòssia externa.

Si en una situació de llengües en contacte existeix diglòssia, és a dir, hi ha aquesta jerarquització i es desplaça les llengües que no són majoritàries, moltes llengües minoritàries (amb pocs parlants) poden convertir-se en minoritzades (es reduïx encara més el nombre de parlants). Ara bé, cada vegada les persones tendeixen més a adquirir una competència plurilingüe i les societats tenen, també, una població lingüísticament més diversa amb unes pràctiques comunicatives més multilingües. Per tal de garantir a tots els parlants la capacitat de combinar el coneixement i l’ús de diverses llengües hauria d’haver-hi un plurilingüisme basat en la justícia.

Si volem que totes les llengües puguen tenir els mateixos drets és lògic que hi haja uns criteris de primacia per als parlants d’una comunitat lingüística en el seu hàbitat històric i que les situacions històriques injustament desfavorables disposen de mesures compensatòries, d’acció afirmativa o discriminació positiva. La igualtat, des d’Aristòtil, és tractar igualment allò que és igual i compensar les desigualtats a fi de reequilibrar-les.

Ara bé, les accions internacionals de caràcter institucional en aquest sentit són extremament febles per avançar cap al plurilingüisme equitatiu. Ni tan sols el reconeixement que el 90 % de les llengües del món pot desaparèixer al llarg d’aquest segle ha fet prendre consciència de la necessitat urgent d’actuar a gran escala per a evitar-ho. Algunes mesures que es podrien prendre serien:

-

establir un marc constitucional que reconega la diversitat lingüística com un capital humà valuós que multiplica les capacitats de relació, tant en l’àmbit cultural com en el món econòmic i per a la cohesió social

-

reconéixer la diversitat i combatre la desigualtat

-

afavorir el coneixement de les llengües arribades recentment a un territori de cara a les relacions culturals o econòmiques amb la resta del món

-

desenvolupar la competència plurilingüe i intercultural

-

mantenir una perspectiva interlingüística oberta: adaptació de manlleus i desenvolupament de capacitats de creativitat lingüística.

Destaquen campanyes de difusió i informació per la igualtat lingüística en cartells i en vídeo com “Igualtat lingüística és…” del Servei de Política Lingüística de la Universitat de València.

De la mateixa manera que no hi ha motius per discriminar els éssers humans, tampoc no hi ha motius per discriminar les llengües. Tot i que la Declaració Universal de Drets lingüístics reconeix que «Tota persona té dret a rebre l’ensenyament en la llengua pròpia del territori on resideix» (Article 29/1), les dades d’Ethnologue mostren que un 35 % de nens del món comencen la seva educació en una llengua que no els és familiar.

La llengua és, per definició, un factor de cohesió o també pot ser de discriminació social. La psicologia social distingeix, en aquest context, dos tipus de motivacions per a l’aprenentatge de l’idioma: les motivacions integratives (o simbòliques), que es refereixen a l’interés dels parlants per incorporar-se a un grup lingüístic; i les motivacions instrumentals, que van dirigides a les possibilitats de promoció i èxit socioeconòmic que ofereixen les llengües. Les polítiques lingüístiques exitoses -com les d’Israel, per exemple- són el resultat de combinar creativament aquesta fèrtil ambivalència. El cas irlandès, contràriament, és un exemple de simbolització de la llengua al marge dels seus usos reals. La República d’Irlanda és un Estat europeu amb una sola llengua nacional: l’anglès. L’emfàtica declaració constitucional («La llengua irlandesa, com a llengua nacional, és la primera llengua oficial d’Irlanda») no ha evitat que el gaèlic sigui un idioma residual socialment i geogràficament.

“Els valencianoparlants estan cada vegada més decidits a denunciar els atacs a la llengua”

Natxo Badenes, president d’Escola Valenciana, en una entrevista a Les notícies del matí

d’À punt (3-12-2021)

D’altra banda, els casos de discriminació lingüística solen ser habituals. L’entitat Escola Valenciana ha denunciat molts d’aquests casos, com el d’una família que es queixa del tracte rebut per una administrativa d’un centre de salut d’Alº acant, la qual es va negar a atendre’ls fins que no li parlaren en castellà.

Imatge extreta de la notícia: Escola Valenciana denuncia una nova discriminació lingüística a Alacant: «O em parles en castellà o no podrem atendre la teua filla» (Vilaweb, 25-9-22)

Aquesta família explica la situació «d’absoluta vulnerabilitat» en què es van trobar, quan la treballadora els va etzibar «o em parles en castellà o no podrem atendre la teua filla». A més, assevera que «no és admissible que et facen triar entre que atenguen la teua filla o poder-te expressar en la teua llengua». Escola Valenciana assenyala que aquesta no és una situació aïllada. L’àmbit sanitari viu una situació alarmant, ja que concentra 1 de cada 2 vulneracions recollides a l’Oficina de Drets Lingüístics de l’entitat.

Escola Valenciana posa a disposició de qualsevol persona que ho necessite els seus recursos perquè cap vulneració lingüística quede sense resposta i informa que davant de qualsevol queixa, com en aquest cas, l’entitat s’adreça al Síndic de Greuges, l’Oficina de Drets Lingüístics de la Generalitat i la institució corresponent: la Conselleria de Sanitat, en aquest cas.

En la secció de discriminació lingüística dels diaris La Veu, ARA i Vilaweb es troben més exemples de denúncies.

Gràfic extret de Tena, V. (2022): Discriminacions lingüístiques de rècord. El Temps.

LLENGÜES VULNERABLES

La diversitat sovint s’ha considerat un problema. La gran majoria de llengües del món són avui molt vulnerables. Una part important desapareixerà les pròximes dècades, però no es tracta d’un procés espontani, sinó provocat per un projecte uniformitzador que provoca patiment i que és símptoma de la propensió a la dominació i a l’exclusió i de poca capacitat de conviure amb la diversitat.

El perill que desapareguin centenars de llengües com a resultat d’una imposició és que pot minar l’autoestima, convertir les persones en vulnerables, generar autoodi. A més, és símptoma d’un món en què la diversitat es veu com un problema o fins i tot com una ofensa. No cal esborrar una llengua per adquirir-ne una altra. La vulnerabilitat de la diversitat lingüística és la vulnerabilitat d’un món que no és capaç de conviure sense renunciar a la diversitat.

Text extret de Comellas Casanova, P.2021 «Llengües vulnerables: la diversitat lingüística en perill». Compàs d’amalgama, Núm. 4, p. 44-48. https://raco.cat/index.php/compas/article/view/392781