European regulations

2.2 EUROPEAN REGULATIONS

“All languages are the expression of a collective identity and of a distinct way of perceiving and describing reality and must therefore be able to enjoy the conditions required for their development in all functions,”

Article 7, Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights

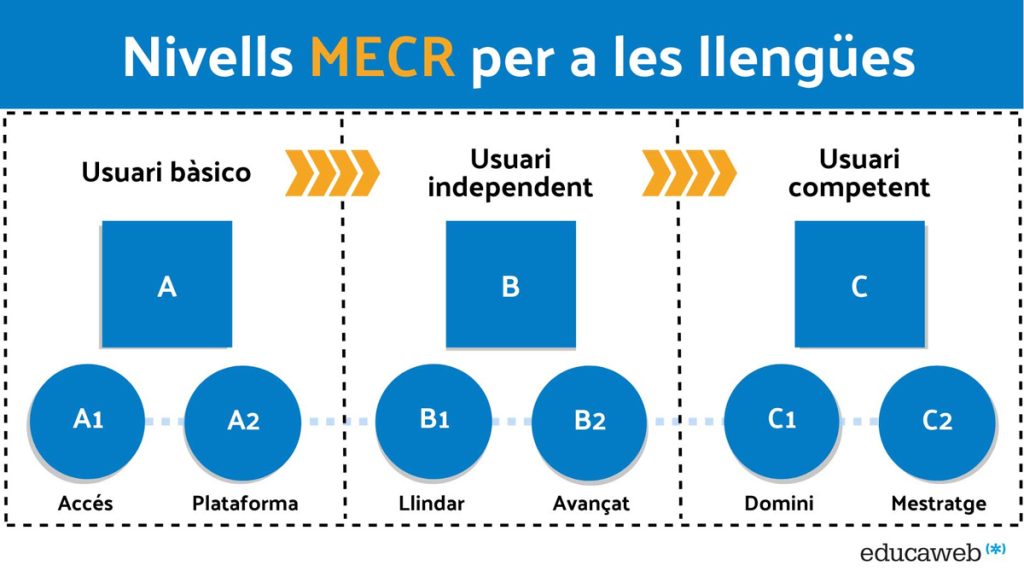

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) is a part of the linguistic policy guidelines of the European Union (EU) based on the motto “united in diversity.” The Council of Europe recommends since 2001 its use to the member States. The 1992 Treaty on the European Union (TEU) in its third Chapter already established that they will fully respect “the responsibility of the Member States for the content of teaching and the organization of education systems and their cultural and linguistic diversity” and the Treaty on the Functioning (TFEU in its 2016 consolidated version), in article 165.2, specifies that they would “develop education, particularly through the teaching and dissemination of the languages of the Member States.”

Image 2: CEFR levels. From Educaweb

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, approved in 1992, proposes the learning of minoritarian languages and its use in different fields of relationship between the citizens and the institutions of the different countries. The Charter is an international convention or treaty that has been ratified by the Spanish government and that, as per article 96 of the Constitution, is now integrated in the Spanish code of law. It is the base on which the protection and enhancement of all regional or minoritarian traditional languages in Europe can be organized, since each of the languages partakes in the European linguistic diversity, and all of them contribute “to the maintenance or development of cultural wealth in Europe.”

Image 3: Cover of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The Charter is the only legally binding international treaty devoted exclusively to the protection and promotion of regional and minority languages. So far, the Charter includes around 80 languages from over 200 linguistic communities.

In the ratification instrument, Spain declares that regional or minoritarian languages are “languages that are considered official in the self-government statutes in the Basque Country, Catalonia, Balearic Islands, Galicia, Valencia and Navarra” and those that “self-government status protect and shelter in the territories where they are traditionally spoken.”

The Charter has two kinds of agreements:

1.The ones included in Part II that affect all regional or minoritarian languages of a particular country and that contain a list of objectives and principles that the State must base its policies, legislation and practices on.

2. The ones included in part III, where the State has to choose “on demand” a particular number (at least, 35).

Part IV of the Charter regulates the control mechanism of these agreements. As per the procedure defined in the Charter itself to assess the compliance with its provisions, the governments of the member States that have ratified it must periodically send a report on the measures taken for its compliance. This report, as well as the reports sent periodically by other non-governmental institutions devoted to the promotion and dissemination of these languages, the additional information that can be requested and, if it is the case, the information obtained in situ by observers and delegate experts, helps the Committee of Experts defined in article 17 of the Charter to publish its own assessment report and the recommendations that it then presents to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.

Since 2002, the Spanish government has presented five reports, the last of which corresponds to the period 2014-2016.

-

Ratification instrument of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages as published in the BOE

-

Text of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

-

Explanatory report for the ECRML

-

5th report of the Committee of Experts for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) and its application in Spain

-

Recommendations of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the application on the ECRML

-

Report of the Committee of Experts to assess the recommendations of immediate action contained in the 5th report of the Committee of Experts of the ECRML

-

Website of the Council of Europe with information on the ECRML

In article 7 we find the twelve general principals to be applied to all languages (Puig 2002,206-207):

(1) “The recognition of the regional or minority languages as an expression of cultural wealth.

(2) The respect of the geographical area of each regional or minority language.

(3) The need for resolute action to promote regional or minority languages in order to

safeguard them.

(4) The facilitation and/or encouragement of the use of regional or minority languages, in speech and writing, in public and private life;.

(5) The maintenance and development of links, in the fields covered by this Charter, between groups using a regional or minority language and other groups in the State employing a language used in identical or similar form, as well as the establishment of cultural relations with other groups in the State using different languages.

(6) The provision of appropriate forms and means for the teaching and study of regional or minority languages at all appropriate stages.

(7) The provision of facilities enabling non-speakers of a regional or minority language living in the area where it is used to learn it if they so desire.

(8) The promotion of study and research on languages.

(9) The promotion of appropriate types of transnational exchanges for regional or minority languages used in identical or similar form in two or more States.

(10) The Parties undertake to eliminate any unjustified distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference relating to the use of a regional or minority language and intended to discourage or endanger the maintenance or development of it.

(11) The Parties undertake to promote, by appropriate measures, in favor of minority languages with the objective to promote equality between their speakers and the rest of the population, considering its particular situation, and not considering it an act of discrimination regarding the speakers of more frequently used languages.

(12) The respect, understanding and tolerance towards minoritarian languages must count among the education and training objectives in the country, stimulating the media to pursue the same objective.”

In most States in the European Union more than one language is spoken and the protection and official recognition varies despite the regulations established by the European Charter of Regional and Minority Languages. In this contest, Catalan should not be considered a minoritarian language. Data place it in a position remarkably similar to Swedish, Greek or Portuguese in Europe, all of them languages that are fully acknowledged because they are State languages.

Therefore, if we compare the main minoritarian languages in the EU, Catalan is in the first position when considering the number of speakers. We can say that, despite being a medium-sized language when we think of the number of speakers, Catalan is a minoritized language.

.

-

Language

Speakers

1. Catalan 9,118,000

2. Galician 2,420,000

3. Occitan 2,100,000

4. Sardinian 1,300,000

5. Basque 683,000

6. Gaelic 508,000

7. Frisian 400,000

8. Friulian 400,000

9. Luxembourgian 350,000

10. Breton 180,000

11. Corsican 125,000

Total EU: 49,000,000

Minoritarian languages in the EU and number of speakers. Source: Intercat.cat-Lingcat

Linguistic rights

In 1996 The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights stated that a basic principle: linguistic rights are, at the same time, individual and collective, because the language is established and made available within a community, even though it is used individually.

Linguistic law is a field within legal knowledge that is devoted to the study of questions stemming from the existence of several languages that share a common territory and that intends to define the frame of how they are studied and used.

Image 4: Cover of The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights (1998) Comitè de Seguiment de la Declaració Universal dels Drets Lingüístics. Diputació de Barcelona

Linguistic rights are established in The Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights, that states the equality with no distinction between official and non-official, national, regional or local, majoritarian or minoritarian, and modern or archaic languages. Linguistic Law includes the right to be acknowledged as member of a linguistic community, to use the language in private and public, to use the name of the language, the right to engage socially with other members of the linguistic community, and the right to sustain and develop the own culture.

Image 5: extracted from Decàleg dels Drets lingüístics del valencià [El Tempir]

You can check this on-line: Decàleg per a ser lingüísticament sostenible

European Network to Promote Linguistic Diversity

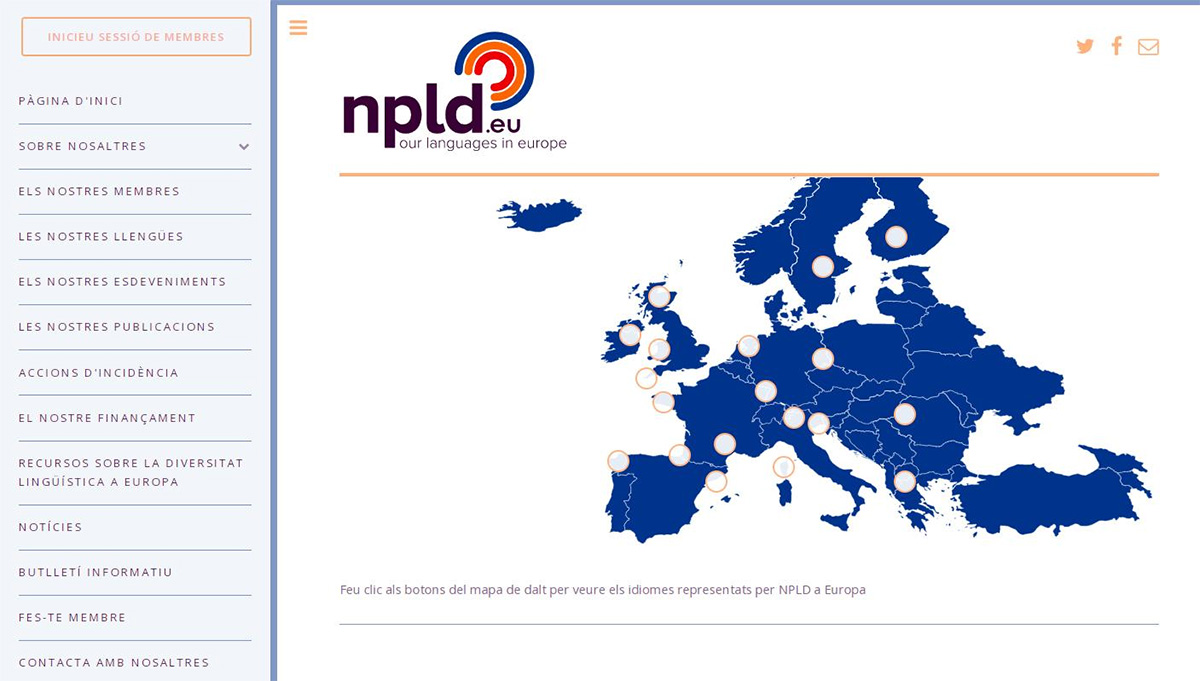

The Network to Promote Linguistic Diversity (NPLD) is a network that integrates regional and national governments, universities, and associations that work in linguistic policies and planification.

Image 6: Web of the European Network to Promote Linguistic Diversity

The main goal of the NPLD is to create an awareness regarding the importance of linguistic diversity, a common value for all Europeans that requires support and promotion from the main European institutions. In this sense, the NPLD works closely with the Commission, the Parliament and the Council of Europe, and acts as link between institutions and the regional department specialized in linguistic promotion, to link them together in order to exchange good practices and successful experiences.

On February 12th, 2016, the Directorate-General for Linguistic Policies and Multilingualism informed the Council of the inclusion of the Generalitat Valenciana as a full member of the NPLD.

Linguistic policies

Siguan, M. in L’Europa de les llengües (1995) has classified linguistic policies of the European member States in five types:

(1) Monolingualism in practice and as an objective: Portugal, Germany, France, Italy and Greece. There are obvious nuances. Italy has a certain degree of linguistic autonomy. Germany recognizes the Frisian and Danish minorities, while France and Greece have been so absurdly Jacobin that they have ratified, or rather, torpedoed, the European Charter of Regional and Minority Languages.

(2) Protection of minorities. The United Kingdom and the Netherlands give a certain acknowledgement to their Gaelic and Frisian minorities, respectively.

(3) Linguistic autonomy. Spain, for example, recognizes non-Castilian languages officially in their respective regions.

(4) Linguistic federalism. In the central government bodies the languages of all citizens are equality represented. Dutch and France in Belgium, and Italian, German, Romansh (secondarily) and French in Switzerland. However, each one of the areas is monolingual.

(5) Institutional bilingualism. Everywhere, both in central bodies and in some of the regional or local authorities, there is bilingualism. This happens in Ireland, Luxembourg, and Finland.

Official linguistic philosophy

“Europe should be a space where no language requires guardianship or protection in order to exist. It should be an area in which the different languages spoken there could develop freely, driven only by those who use them maturely and responsibly.” (Argemí 1996,17).

If we take a look at the European Commission leaflet (2004) and the linguistic policy report presented to the European Parliament (2005), we find the EU philosophy in linguistic policies: to actively promote the peoples’ freedom to write and speak in their own language.

The Commission’s multilingualism policy has three objectives:

(a) encourage the learning of languages and linguistic diversity in society

(b) foster a healthy multilingual economy (sic)

(c) give access to the citizens to the European Union laws, procedures, and information in their own language.

The Union claims to respect minority and regional languages (articles 20 and 21 in the 200 Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union). Three possible situations are considered:

(a) Regional settlements, totally or partially, in one or several States (Basque, Breton, Catalan, Frisian, Sardinian, Gaelic).

(b) Minorities in a State, that are official and completely “normal” (German in Denmark, Danish in Germany).

(c) Non-territorial languages (Yiddish or Romani).

We notice that the languages derived from new migrations (Turkish, Kurdish Arabic, Berber…) are not included, even if they might have more speakers than indigenous languages, as is the case of Arabic. As Marí (2006,124-5) states, we can clearly see two rationalities in the EU. On one hand, citizens are particularly worried about the effects that the integration in the EU have or will have on the pre-existing linguistic diversity. On the other, the leaders seem more devoted to identifying the issues and implications of the European linguistic diversity for the integration process. Marí has also summarized really well how the European linguistic policy is neither systematic nor global nor explicit (Marí 2006, 125- 6).

One or more languages can work as interlanguages, but should not systematically substitute local languages: what the local language can take care of should not be taken care of by the more global language (Bastardas 2005). We must ultimately find an ecological vision of linguistic diversity management: we can only manage what we know and are concerned about (10 tesis… 2000, and Informe…2005). Let us repeat the epigraphs of the 10 thesis for a plausible future for languages and cultures:

(1) Languages are both systems to interpret reality and means of communication.

(2) Languages evolve depending on the adaptation of the linguistic communities to new circumstances

(3) Universal linguistic diversity is a positive fact.

(4) Situations when there is linguistic contact are positive when ruled by linguistic ethic criteria.

(5) All languages are equally worthy.

(6) Plurilingual education is a complement to the search of linguistic self-esteem.

(7) Each and every language is a human heritage.

(8) Linguistic security is a condition to democratic participation.

(9) The acknowledgement of linguistic diversity is one of the conditions for peace.

(10) The protection of linguistic diversity is an option in favor of a more plural and harmonic world.

Europe, therefore, can refute the myth of Babel that has made many people believe that linguistic diversity was a curse. Europe can prove that equality in rights does not necessarily mean equality in traits (sameness). This struggle for respect, acknowledgement and even encouragement of diversity must be used as well to improve the dialogue with new diversities that come from outside Europe.

Europe has always been a plural entity, a complex melting-pot of people and identities (Bauman 2006). Realizing this helps us accept with no distrust the diversity that comes from outside Europe, due to human movements that are particularly intense today, but that have always existed. States, regions, cities, and the Union must work to render possible that this diversity becomes a real opportunity for everyone.

Albert Bastardas (2005) has presented basic principles for sustainability in an ecological concept of linguistic diversity. Two are very well know (personality and territoriality) and two are new (functional competence and subsidiarity). At an international scale, both Will Kymlicka and Alan Patten (2003) and Philippe van Parijs (2011) have dealt with the universal principles of justice in the management of linguistic and cultural diversity.

As far as principles are concerned, there are significant coincidences. Beyond the minimum marked by formal equality between linguistic communities and the speakers that coexist in a common territory, it is logical that there are supremacy criteria for the speakers of a linguistic community in their historical habitat and that historical situations that are unfairly unfavorable compel to the use of compensatory measures, of positive action or positive discrimination (equality, since Aristotle, is treating equally what is equal and compensating inequalities in order to recover balance).

Sadly, international actions with an institutional character in this sense are extremely weak and are mostly limited to declarations with no effective results. There is no perspective of seeing an advance towards an equitable world-wide plurilingualism in the United Nations’ agreements, the UNESCO declarations or the actions taken by the European Union (that seemed about to lead an world-wide process of this time in a certain moment in time). Not even acknowledging that 90% of the languages in the world could disappear in this century has raised awareness of the urgent need to act at a global scale to avoid it.

Text extract from Boix-Fuster, Emili (2006): «El plurilingüisme europeu: una introducció». LSC– Llengua, societat i comunicació, 2006, Núm. 4, p. 6-18.

https://raco.cat/index.php/LSC/article/view/5173

2.2 REGULACIONS EUROPEES

“Totes les llengües són l’expressió d’una identitat col·lectiva i d’una manera distinta de percebre i de descriure la realitat, per tant, han de poder gaudir de les condicions necessàries per al seu desenvolupament en totes les funcions.”

Article 7, Declaració Universal dels Drets Lingüístics

El Marc Comú Europeu de Referència de les Llengües (MCER) s’inclou en les directrius de política lingüística de la Unió Europea (UE) que se sustenta en el lema “unida en la diversitat”. El Consell d’Europa recomana des del 2001 el seu ús als països membres. El Tractat fundacional de la UE (TUE) de 1992, en l’article 3 ja estableix que es “respectarà la riquesa de la seva diversitat cultural i lingüística” i en el Tractat de funcionament (TFUE, versió consolidada en 2016), a l’article 165.2, puntualitza que caldrà difondre i potenciar l’aprenentatge de les diferents llengües dels estats membres.

La Carta Europea de les Llengües Regionals o Minoritàries (CELROM), aprovada el 1992, proposa l’ensenyament de les llengües minoritzades i poder-les fer servir en els diferents àmbits de relació entre la ciutadania i les institucions del país en qüestió. La Carta és una convenció o tractat internacional, ratificat per l’Estat espanyol, que d’acord amb el que estableix l’article 96 de la Constitució, ha passat a formar part de l’ordenament jurídic espanyol. Pretén ser la base sobre la qual es puga organitzar la protecció i el foment de totes les llengües regionals o minoritàries tradicionals d’Europa, ja que cada llengua forma part de la diversitat lingüística d’Europa i totes aquestes contribueixen «al manteniment i al desenvolupament de les tradicions i la riquesa culturals d’Europa».

La Carta és l’únic conveni internacional legalment vinculant destinat exclusivament a la protecció i la promoció de les llengües regionals i minoritàries. Fins avui, a la Carta s’hi inclouen al voltant de 80 llengües de més de 200 comunitats lingüístiques.

En l’instrument de ratificació Espanya declara que s’entenen per llengües regionals o minoritàries les «llengües reconegudes com a oficials en els estatuts d’autonomia de les comunitats autònomes del País Basc, Catalunya, Illes Balears, Galícia, València i Navarra»; i aquelles que «els estatuts d’autonomia protegeixen i emparen als territoris on tradicionalment es parlen».

La Carta té dos grups de compromisos:

1. Els que s’inclouen en la part II, que afecten totes les llengües regionals o minoritàries d’un estat i que contenen una llista d’objectius i principis en què l’Estat ha de basar les seues polítiques, la seua legislació i les seues pràctiques.

2. Els que s’inclouen en la part III, dels quals l’Estat n’ha de triar «a la carta» un nombre determinat (almenys, 35).

La part IV de la Carta regula el mecanisme de control dels compromisos. D’acord amb el procediment que la mateixa Carta preveu per avaluar el compliment de les seues disposicions, els governs dels estats membres que l’han ratificada han d’enviar periòdicament un informe sobre les mesures preses per al seu compliment. Aquest informe, juntament amb els informes que amb la mateixa periodicitat lliuren altres institucions no governamentals dedicades al foment i la difusió d’aquestes llengües, les ampliacions d’informació que sol·liciten i, si escau, la informació obtinguda in situ pels observadors i experts delegats, serveix al Comité d’Experts previst a l’article 17 de la Carta per emetre el seu informe d’avaluació i la proposta de recomanacions que presenta al Comité de Ministres del Consell d’Europa.

Des de 2002 l’Estat espanyol ha presentat cinc informes l’últim dels quals correspon al període 2014-2016.

-

Instrument de ratificació de la Carta Europea de les Llengües Regionals o Minoritàries publicat al BOE

-

Text de la Carta Europea de les Llengües Regionals o Minoritàries

-

Informe explicatiu de la CELROM

-

5è informe del Comité d’Experts de la Carta Europea de Llengües Regionals o Minoritàries (CELROM) sobre la seua aplicació a Espanya

-

Recomanacions del Consell de Ministres del Consell d’Europa als estats membres sobre l’aplicació de la CELROM

-

Informe del Comité d’Experts d’avaluació de les recomanacions d’acció immediata contingudes en el 5è informe d’avaluació del Comité d’Experts sobre la CELROM

-

Lloc web del Consell d’Europa amb informació sobre la CELROM

En l’article setè trobem els dotze principis generals que s’han d’aplicar a totes les llengües (Puig 2002,206-207):

(1) “El reconeixement de les llengües com a expressió de la riquesa cultural.

(2) El respecte de l’àrea geogràfica de cada llengua.

(3) La necessitat d’una acció resolta de foment de les llengües amb el fi de salvaguardar-les.

(4) L’obligació de facilitar i encoratjar l’ús oral i escrit de les llengües en la vida pública i privada.

(5) El manteniment i desenvolupament de relacions en els àmbits de la Carta entre els grups que usen una llengua idèntica o semblant, i de relacions culturals amb els altres grups de l’estat que usin llengües diferents.

(6) La provisió de les formes i els mitjans adequats per a l’ensenyament i l’estudi de les llengües a tots els nivells necessaris.

(7) La provisió de mitjans que permetin l’aprenentatge de la llengua als no parlants, que resideixin en l’àrea on aquesta és parlada.

(8) La promoció d’estudis i investigacions sobre les llengües.

(9) La promoció d’intercanvis transfronterers per a les llengües parlades de manera idèntica o semblant en dos o més estats.

(10) L’eliminació de tota distinció, exclusió, restricció o discriminació que tingui per objecte desanimar o posar en perill el manteniment i desenvolupament d’una llengua.

(11) La consideració que l’adopció de mesures especials a favor de les llengües minoritàries amb l’objectiu de promoure la igualtat entre els seus parlants i la resta de la població, tenint en compte les seves situacions peculiars, no es podrà considerar un acte de discriminació en relació amb els parlants de les llengües més esteses.

(12) El respecte, la comprensió i la tolerància envers les llengües minoritàries han de figurar entre els objectius de l’educació i la formació impartides en el país, estimulant els mitjans de comunicació a perseguir el mateix objectiu”.

A la majoria dels estats de la Unió Europea s’hi parla més d’una llengua amb un molt divers grau de protecció i de reconeixement oficial malgrat el que estipulen les disposicions de la Carta Europea de les Llengües Regionals i Minoritàries. En aquest marc, la situació del català no s’hauria de considerar com una llengua minoritària. Les dades la situen en una posició molt similar al suec, el grec, el portugués a Europa, unes llengües que compten amb un ple reconeixement perquè són la llengua de l’estat.

Alhora, si comparem les principals llengües minoritàries a la UE, el català se situaria en la primera posició pel que fa al nombre de parlants. Podem dir, que tot i ser una llengua mitjana pel que fa al nombre de parlants, el català és una llengua minoritzada.

|

Llengua |

Parlants |

|

1. Català 9.118.000 2. Gallec 2.420.000 3. Occità 2.100.000 4. Sard 1.300.000 5. Eusquera 683.000 6. Gal·lès 508.000 |

7. Frisó 400.000 8. Friülés/furlà 400.000 9. Luxemburgués 350.000 10. Bretó 180.000 11. Cors 125.000 Total UE: 49.000.000 |

Llengües minoritàries de la UE i nombre de parlants. Font: Intercat.cat-Lingcat

Drets lingüístics

El 1996 la Declaració Universal dels Drets Lingüístics afirmava un principi bàsic: els drets lingüístics són alhora individuals i col·lectius, perquè la llengua es constitueix i es fa disponible en el si d’una comunitat, encara que siga usada individualment.

El dret lingüístic és una especialitat del saber jurídic que té com a objecte d’estudi les qüestions derivades de l’existència de diverses llengües en un mateix territori i que s’ocupa de definir-ne el marc d’aprenentatge i ús.

Els drets lingüístics s’estableixen en la Declaració Universal dels Drets Lingüístics, on es proclama la igualtat sense distincions entre llengües oficials i no oficials; nacionals, regionals i locals; majoritàries i minoritàries, o modernes i arcaiques. El dret lingüístic inclou el dret a ser reconegut com a membre d’una comunitat lingüística, a l’ús de la llengua en privat i en públic, a l’ús del propi nom, el dret de relacionar-se i d’associar-se amb altres membres de la comunitat lingüística d’origen i el dret de mantenir i desenvolupar la pròpia cultura.

![Imatge 5: extreta del Decàleg dels Drets lingüístics del valencià [El Tempir]](https://titlenet.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/img05.jpg)

Podeu consultar aquest catàleg en línia: Decàleg per a ser lingüísticament sostenible

Xarxa Europea per a la Diversitat Lingüística

La Xarxa Europea per a la Diversitat Lingüística (NPLD, en les sigles en anglés) és una xarxa que compta, entre els seus membres, amb governs estatals i regionals, universitats i associacions que treballen en el camp de la política i la planificació lingüístiques.

L’objectiu principal de la NPLD és crear consciència sobre la importància de la diversitat lingüística, un valor comú de tots els europeus que necessita el suport i la promoció de les màximes institucions europees. Per aquest motiu, la NPLD treballa estretament amb la Comissió, el Parlament i el Consell d’Europa i fa de pont entre les institucions i els departaments regionals especialitzats en la promoció lingüística, relacionats també entre si amb la finalitat d’intercanviar bones pràctiques i experiències reeixides.

El 12 de febrer de 2016 la Direcció General de Política Lingüística i Gestió del Multilingüisme va informar el Consell de la incorporació de la Generalitat Valenciana com a membre de ple dret de la NPLD.

Polítiques lingüístiques

Siguan, M. en L’Europa de les llengües (1995) ha classificat les polítiques lingüístiques dels estats europeus en cinc tipus:

(1) El monolingüisme com a pràctica i com a objectiu: Portugal, Alemanya, França, Itàlia i Grècia. Evidentment hi ha matisos. Itàlia té un cert grau d’autonomia lingüística, Alemanya reconeix les seves minories frisona i danesa, mentre que França i Grècia han estat tan furibundament jacobins que han ratificat ridículament – o millor dit, han torpedinat- la Carta Europea de les Llengües regionals i minoritàries.

(2) La protecció a les minories. El Regne Unit i Holanda donen un cert reconeixement a les seves minories gal·lesa i frisona respectivament;

(3) L’autonomia lingüística. Espanya, per exemple, reconeix oficialment les llengües no castellanes en les respectives autonomies.

(4) El federalisme lingüístic. En els òrgans centrals de l’estat estan representades de manera igualitària totes les llengües dels ciutadans, neerlandès i francès en el cas belga, i italià, alemany, romanx (de manera secundària) i francès en el cas helvètic. En canvi, en cada zona hi ha monolingüisme.

(5) Bilingüisme institucional. Arreu, tant en els òrgans centrals com en alguns dels òrgans regionals o locals hi ha bilingüisme. és el que succeeix a Irlanda, Luxemburg i Finlàndia.

La filosofia lingüística oficial

“Europa hauria de ser un espai en què cap llengua no hagués d’esperar ser tutelada o protegida per existir; hauria de ser una àrea en què les diverses llengües que es parlen es desenvolupessin lliurement, amb l’única força dels qui les usen d’una manera madura i responsable” (Argemí 1996,17).

Si examinem el fulletó de la Comissió Europea (2004) i l’informe de política lingüística presentat al Parlament Europeu (2005) trobem la filosofia de la UE en política lingüística: promoure activament la llibertat dels seus pobles a parlar i a escriure en la seva llengua.

La política de multilingüisme de la Comissió té tres objectius:

(a) fomentar l’aprenentatge d’idiomes i la diversitat lingüística a la societat

(b) promoure una economia multilingüe sana (sic)

(c) donar accés als ciutadans a la legislació, als procediments i a la informació de la Unió Europea en el propi idioma.

La Unió proclama el seu respecte per les llengües minoritàries i regionals (articles 20 i 21 de la Carta dels drets fonamentals de la Unió Europea 2000). Es tenen en compte tres situacions:

(a) Enclavaments regionals, totalment o parcialment, en un o diversos estats (basc, bretó, català, frisó, sard, gal·lés)

(b) Minories en un estat, que són oficials i completament “normals”, en un altre (alemany a Dinamarca o Itàlia, danès a Alemanya)

(c) Llengües no territorials (ídix, romaní)

Observem que no s’inclouen les llengües de les noves migracions (turc, kurd, àrab, berber…) tot i que poden tenir més parlants que les llengües autòctones, per exemple, l’àrab. Podem constatar, seguint Marí (2006,124-5), dues lògiques en la construcció lingüística de la UE. D’una banda, els ciutadans estan preocupats sobretot en els efectes que té i tindrà la integració europea sobre la diversitat lingüística existent. D’altra banda, els dirigents semblen més preocupats en els inconvenients i les implicacions que comporta la diversitat lingüística europea per al procés d’integració. També Marí ha resumit molt bé com la política lingüística europea no és ni sistemàtica, ni global, ni explícita (Marí 2006, 125- 6).

Una o més llengües poden funcionar com a interllengües, però no haurien de substituir sistemàticament les llengües locals: el que pugui fer la llengua local que no ho faci la llengua més global (Bastardas 2005). Cal, en definitiva, una visió ecològica de la gestió de la diversitat lingüística: sols gestionarem allò que coneixem i ens preocupa (10 tesis… 2000, i Informe…2005). Recordem els epígrafs de les 10 tesis per a un futur plausible de les llengües i de les cultures:

(1) Les llengües són, a la vegada, sistemes d’interpretació de la realitat i mitjans de comunicació.

(2) Les llengües evolucionen en funció de l’adaptació de les comunitats lingüístiques a circumstàncies noves.

(3) La diversitat lingüística universal és un fet positiu.

(4) Les situacions de contacte lingüístic són positives quan es regeixen per criteris d’ètica lingüística.

(5) Totes les llengües són iguals en dignitat.

(6) L’educació plurilingüe és complementària de la invitació a l’autoestima lingüística.

(7) Cada una de les llengües és patrimoni de la humanitat.

(8) La seguretat lingüística és una de les condicions de la participació democràtica.

(9) El reconeixement de la diversitat lingüística és una de les condicions de la pau.

(10) La protecció de la diversitat lingüística és una opció a favor d’un món plural i harmònic.

Europa, en definitiva, pot rebatre el mite de Babel que ha fet creure a molta gent que la diversitat lingüística era una maledicció: Europa pot demostrar que la igualtat de drets (equality) no ha de voler dir necessàriament igualtat de característiques (sameness). Aquesta lluita pel respecte, reconeixement i fins i tot encoratjament de la diversitat ha de servir també per millorar el diàleg amb les noves diversitats que ens arriben de fora d’Europa.

Europa sempre ha estat una realitat plural, una complexa amalgama de pobles i identitats (Bauman 2006). Adonar-nos d’això ens fa acceptar sense recels la diversitat que ve de fora, fruit d’uns moviments humans que són especialment intensos en l’actualitat, però que han existit sempre. Els Estats, les Regions, els Municipis i la Unió, han de vetllar per fer possible que aquesta diversitat esdevingui una oportunitat real per a tothom.

Albert Bastardas (2005) ha exposat uns principis bàsics per a la sostenibilitat en un concepte ecològic de la diversitat lingüística: dos de ben coneguts (el de personalitat i el de territorialitat) i dos de nous (el de suficiència funcional i el de subsidiarietat). A escala internacional, tant Will Kymlicka i Alan Patten (2003) com Philippe van Parijs (2011) s’han ocupat dels principis universals de justícia en la gestió de la diversitat lingüística i cultural.

En aquest terreny de principis hi ha coincidències significatives. Més enllà dels mínims de la igualtat formal entre les comunitats lingüístiques i els parlants que coexisteixen en un mateix marc, és lògic que hi haja uns criteris de primacia per als parlants d’una comunitat lingüística en el seu hàbitat històric i que les situacions històriques injustament desfavorables disposin de mesures compensatòries, d’acció afirmativa o discriminació positiva (la igualtat, des d’Aristòtil, és tractar igualment allò que és igual i compensar les desigualtats a fi de reequilibrar-les).

Lamentablement, les accions internacionals de caràcter institucional en aquest sentit són extremament febles i es limiten gairebé a declaracions sense resultats efectius. No hi ha perspectives que avancin cap al plurilingüisme mundial equitatiu ni els acords de les Nacions Unides, ni les declaracions de la UNESCO, ni les actuacions de la Unió Europea (que en algun moment semblava que podia liderar un procés mundial d’aquest tipus). Ni tan sols el reconeixement que el 90 % de les llengües del món pot desaparèixer al llarg d’aquest segle ha fet prendre consciència de la necessitat urgent d’actuar a gran escala per a evitar-ho.

Text extret de Boix-Fuster, Emili (2006): «El plurilingüisme europeu: una introducció». LSC– Llengua, societat i comunicació, 2006, Núm. 4, p. 6-18. https://raco.cat/index.php/LSC/article/view/5173