Educational ecosystem: connection between agents, spaces and educational time

6.3. EDUCATIONAL ECOSYSTEM: CONNECTION BETWEEN AGENTS, SPACES AND EDUCATIONAL TIMELINE

The organization of the center as a communicative space is a condition for communication to become the nucleus from which verbal and non-verbal linguistic activities are meaningful. In the same vein, relations with other educational centers must be considered as enhancing exchanges that facilitate the realization of learning activities: school correspondence, research, camps, school exchanges… In addition, the center can organize language contexts of use that are diversified and meaningful for the participants. In this area it is very important that the PLCs properly organize the centers in the school zones to facilitate coordination between the different educational levels.

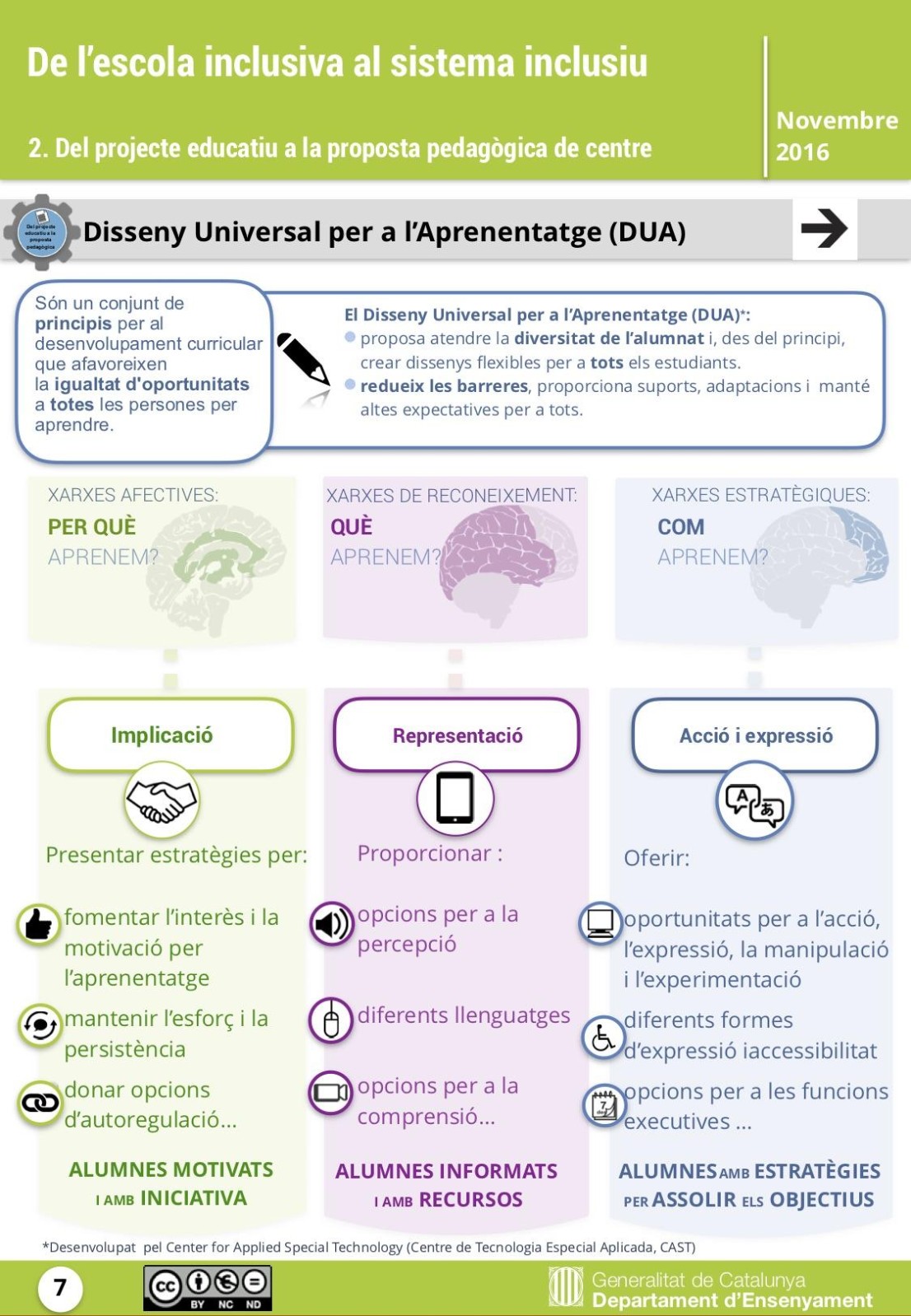

We cannot forget that one of the basic purposes of education is inclusion. Including students with different ways of learning, welcoming all students (whether they are immigrants or not), means changing the teaching methodology or classroom structures that must make interactions between peers and with the teaching staff, and restructure the spaces and time for learning taking into account the promotion of communication between those who educate and those who learn, that is to say, attend to all students, attend differentially to what is different, which also implies think about the organizational structures of schools. In line with what is proposed in this area, it is necessary to think about the relationships between the school, the families and the Parents Association, as much knowledge is grown through the impact that school tasks have at home, and especially by the domestic and cultural activities of the family: the ways of dealing with reading, the habits regarding the use of television or the media, visits to museums or outings to the cinema and the theatre. It is clear that the development of a coherent environment plan can play a role in this whole approach.

Actions that summarize possible proposals to help students progress are:

-

Organize spaces (times and places) for consultation with teachers, in which students who have difficulties should be helped to understand the causes and resources provided to overcome them (which is not the same as taking supplementary classes). It must be remembered that some students who have well-developed cognitive intelligence may have problems in other types of knowledge, whether emotional or social, which, on the other hand, are basic components of many skills.

-

Facilitate help between peers, so that some students help others and reflecting on the fact that at the same time they reinforce their knowledge (it is well known that a content is better understood when it has to be verbalized and explained to another .

-

Give importance to the establishment of routines related to thinking and action strategies, an aspect that is not contradictory to personalizing them or developing creativity, as long as you reflect with the students on the reasons why they may be suitable and useful (metacognition). For example, what to think about or what steps to follow to write a narrative, to compare, to construct a graph to research or to critically read a text. Even so, once internalized, it will be important to encourage people to think about whether there are better itineraries and to create new ones, promoting that everyone finds their own paths.

-

Design, collect and use various didactic materials for the treatment of specific basic difficulties inside or outside the classroom: especially computer applications, games, simulations or others found on the network or that are manipulative. Avoid repetitive activities such as those that were done and that have not helped some students to learn significantly. There are students who learn better from certain types of activities and specific ways of communicating them, and some students prefer others. It’s worth diversifying.

-

Establish medium-term work contracts with some students, agreeing on the commitments of both parties – the student and his or her teacher and, even, with family members -, which specify well the proposals to progress (going much further beyond the traditional recommendations that “The student must work more, be more attentive, make more of an effort…”), and establishing periodic review mechanisms to assess possible progress.

-

For students with significant learning difficulties, coordinate the action with the specialist support teachers and come up with an action plan suitable to the needs and possibilities of each student. In this case, the assessment must be done in accordance with this individualized support plan.

-

Finally, it will be necessary to constantly create new ways of attending to all types of students, applying large doses of imagination in accordance with the available resources. Each center is different and there are no defined rules or pre-established formulas. We need to discard the rigidity that often results from the organizational and timetable structures of many centers and think of others that are more serviceable to all classes of students.

The objective established within the framework of UNESCO is that all students should complete Compulsory Secondary Education having reached an appropriate level – depending on personal characteristics – in each of the skills and, to achieve this, many current school practices and structures need to be rethought and reinvented.

One of them is related to grade repetition: all studies show (for example, those carried out based on the PISA assessments) that repetition falls mainly on students from disadvantaged social environments and only achieve results in a few cases.

Extracted from “Evaluation from an inclusive perspective” in Evaluating is learning

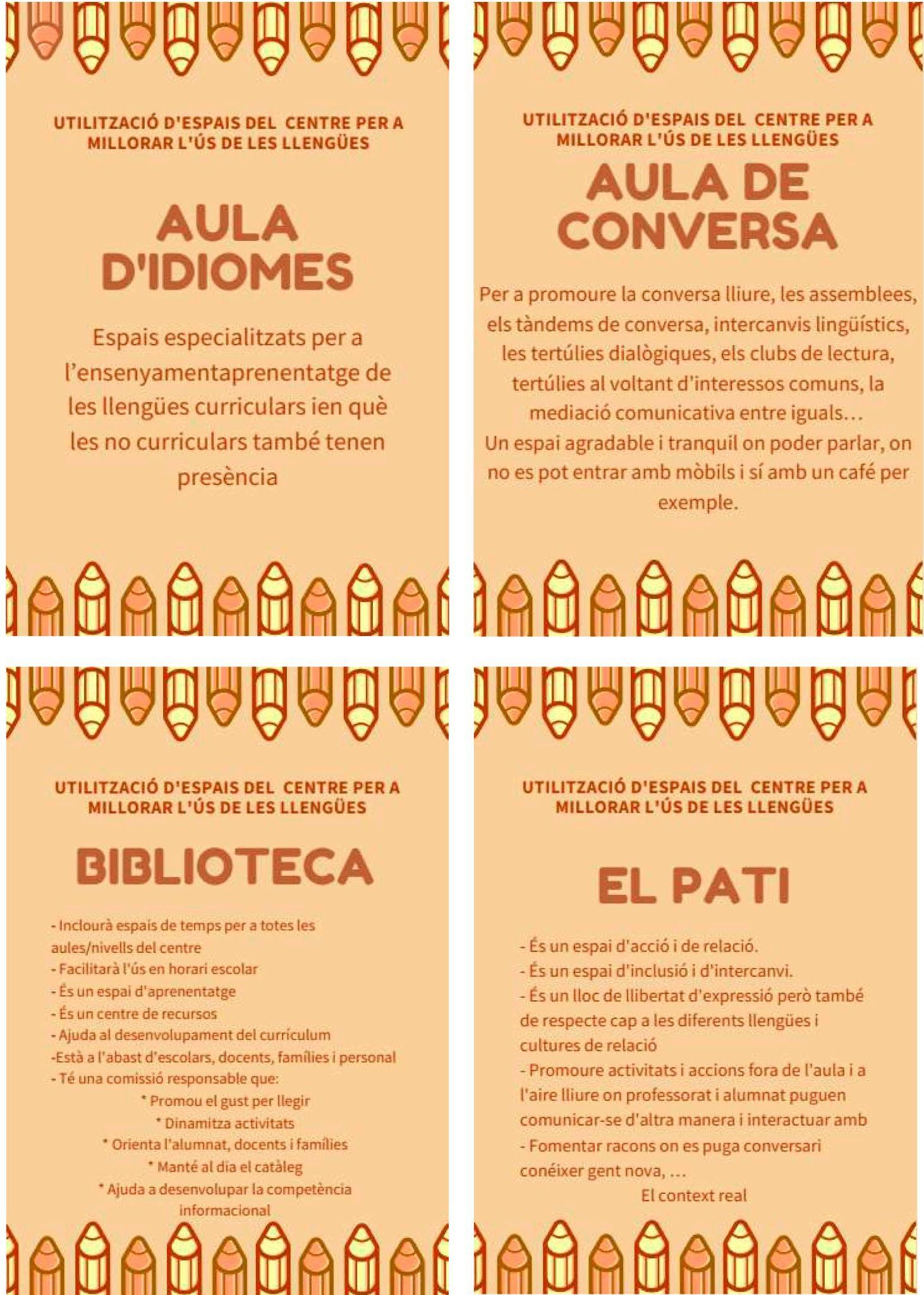

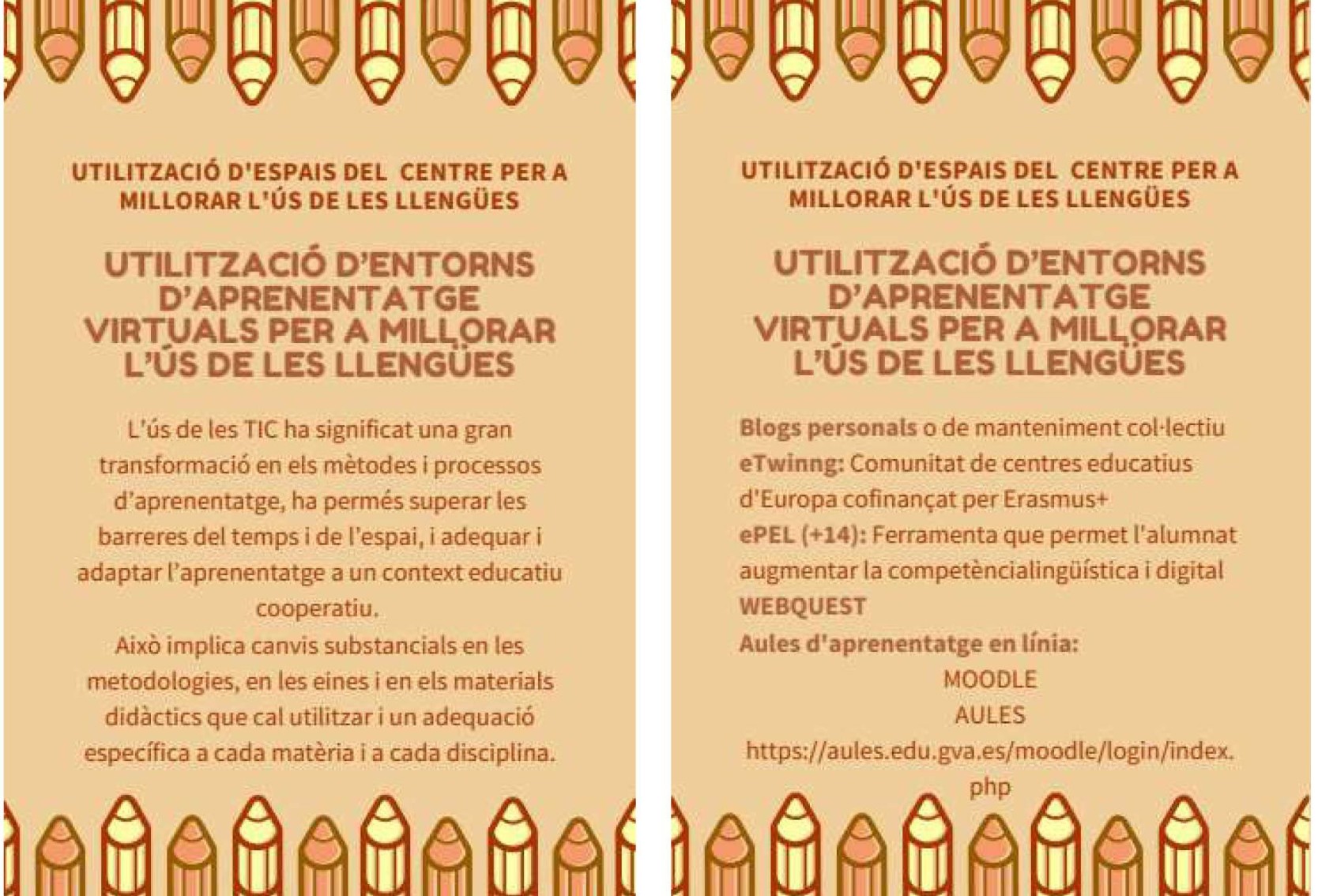

Proposal for the use of spaces in the center to improve the use of languages

Table 6: Use of spaces in the centre to improve the use of languages. Extracted from the Guide for the elaboration of the Language Plan of the Center of the Plurilingual Education Service.

LINGUISTIC ECOLOGY

The fundamental idea is the defense of linguistic diversity. In this sense, the contributions of M. Carme Junyent stand out, especially in the field of education, focused on the recognition, visualization and assessment of diversity (on a global and local scale) and on a critical mistrust towards planning mechanisms based on the power of the state (“the state, especially in its current conception, has been the force that has played the most in favor of linguistic homogenization” (1998: 67)). According to Junyent (1992: 10), “the future of Catalan cannot be separated from the future of all languages and especially all threatened ones. The preservation of linguistic heritage must be global for it to be plausible”. It is necessary to build a new linguistic order that breaks the binomial: one state – one language.

Additionally, we find the works of Jesús Tusón, also with a clear divulgative intention (especially, Tusón, 2004); also Comellas (2006); likewise, works such as Projecte ecolingüística, by Bernat Joan, in this case oriented towards European policies (Joan states the parallelism between threatened languages and species in danger of extinction). It should also be remembered that ecolinguistics, in the area of civic action, has a long history in the Catalan area, as evidenced by institutions such as Ciemen or Linguapax. In recent years, even a government entity, Linguamón, has been created, which is clearly oriented in this direction. Also in the academic field, institutions such as the UNESCO Chair in Languages and Education (directed by Joan A. Argenter), the Linguamón-UOC Chair in Multilingualism (directed by Isidor Marí) or the Threatened Languages Study Group (GELA) ( directed by M. Carme Junyent) focus their research on diversity.

Information extracted from Comellas Casanova, Pere. (2011) «Ecologia lingüística». Treballs de sociolingüística catalana, 21, p. 65-72.

6.3. ECOSISTEMA EDUCATIU: CONNEXIÓ ENTRE AGENTS, ESPAIS I TEMPS EDUCATIU

L’organització del centre com a espai comunicatiu és una condició perquè la comunicació esdevinga el nucli a partir del qual les activitats lingüístiques verbals i no verbals siguen significatives. En aquesta mateixa línia caldrà considerar les relacions amb altres centres educatius com a potenciadores d’intercanvis que faciliten la realització d’activitats d’aprenentatge: correspondència escolar, recerques, colònies, intercanvis escolars… A més, el centre pot articular contextos d’ús lingüístic diversificats i amb sentit per als participants. En aquest àmbit és molt important que els PLC organitzen adequadament els centres de les zones escolars per facilitar la coordinació entre els diferents nivells educatius.

No es pot oblidar que una de les finalitats bàsiques de l’ensenyament és la inclusió. Incorporar alumnes amb diferents maneres d’aprendre, acollir tot l’alumnat (vinga o no de la immigració), vol dir canviar la metodologia de l’ensenyament o les estructures de l’aula que han de fer possibles les interaccions entre iguals i amb el professorat, i reestructurar els espais i el temps per aprendre tenint en compte l’afavoriment de la comunicació entre qui educa i qui aprèn, és a dir, atendre tot l’alumnat, atendre diferencialment el que és diferent, la qual cosa implica també plantejar-se les estructures organitzatives dels centres escolars. En coherència amb el que es planteja en aquest àmbit, caldrà pensar en les relacions entre l’escola i les famílies i les AMPA, perquè molts coneixements són causats pel ressò que tenen a casa les tasques escolars i sobretot per les activitats domèstiques i culturals de la família: les maneres de tractar la lectura, els hàbits respecte a l’ús de la televisió o els mitjans de comunicació, les visites als museus o les sortides al cinema i al teatre. És evident el paper que pot tenir en tot aquest plantejament l’elaboració d’un pla d’entorn coherent.

Accions que resumeixen propostes possibles per ajudar l’alumnat a avançar són:

-

Organitzar espais (temps i llocs) per a la consulta al professorat, en els quals s’hauria d’ajudar tant l’alumnat que té dificultats a entendre’n les causes i proporcionar-li recursos per superar- les (que no és el mateix que fer classes de “reforç” o de “recuperació”), com el que pot anar més enllà i descobrir nous camps per aprofundir. Cal recordar que alguns alumnes que tenen ben desenvolupada la intel·ligència de tipus cognitiu, poden tenir problemes en altres tipus de sabers, sigui de tipus emocional o social, que, d’altra banda, són components bàsics de moltes competències.

-

Facilitar l’ajuda entre iguals, de manera que uns alumnes ajudin els altres i reflexionant entorn del fet que al mateix temps reforcen el seu coneixement (és ben sabut que un contingut s’entén millor quan s’ha de verbalitzar i explicar a un altre.

-

Donar importància a l’establiment de rutines relacionades amb estratègies de pensament i d’acció, aspecte que no és contradictori a personalitzar-les ni a desenvolupar la creativitat, sempre que es reflexioni amb l’alumnat sobre les raons per les quals poden ser idònies i útils (metacognició). Per exemple, en què s’ha de pensar o quins passos s’han de seguir per escriure una narració, per comparar, per construir un gràfic, per investigar o per llegir críticament un text. Així i tot, un cop interioritzades, serà important estimular a pensar en si hi ha millors itineraris i crear-ne de noves, promovent que cadascú trobi els seus propis camins.

-

Dissenyar, recollir i utilitzar materials didàctics diversos per al tractament de dificultats específiques bàsiques dins o fora de l’aula: especialment aplicacions informàtiques, jocs, simulacions o d’altres que es troben a la xarxa o que siguin manipulatius. Evitar activitats repetitives com les que s’han fet quan es va introduir el contingut objecte de regulació i que no han servit a alguns alumnes per aprendre significativament. Hi ha alumnat que aprèn millor a partir d’un tipus d’activitats determinades i de maneres concretes de comunicar-les, i d’altres en prefereixen unes altres. Convé diversificar.

-

Establir contractes de treball a mitjà termini amb alguns alumnes, pactant els compromisos d’ambdues parts —de l’alumnat i del seu professor o professora i, fins i tot, amb familiars—, que concretin bé les propostes per avançar (anant molt més enllà de les tradicionals recomanacions que “ha de treballar més, estar més atent, esforçar-se més…”), i establint mecanismes de revisió periòdics per valorar els possibles avenços.

-

Per als alumnes amb dificultats d’aprenentatge importants, coordinar l’acció amb el professorat de suport especialista i plantejar un pla d’actuació adequat a les necessitats i possibilitats de cada alumne. En aquest cas, l’avaluació s’ha de fer d’acord amb aquest pla de suport individualitzat.

-

Finalment, caldrà inventar constantment noves maneres d’atendre a tota mena d’alumnes, aplicant grans dosis d’imaginació d’acord amb els recursos disponibles. Cada centre és diferent i no hi ha regles definides ni receptes preestablertes. Cal deslliurar-nos de la rigidesa que sovint comporten les estructures organitzatives i horàries de molts centres i pensar en d’altres que estiguin més al servei de tota classe d’alumnat

L’objectiu establert en el marc de la UNESCO és que tot l’alumnat hauria de finalitzar l’Educació Secundària Obligatòria havent arribat a un nivell idoni —en funció de les característiques personals— en cadascuna de les competències i, per aconseguir-ho, cal repensar i reinventar moltes de les pràctiques i estructures escolars vigents.

Una d’elles es relaciona amb la repetició de curs: tots els estudis demostren (per exemple, els realitzats a partir de les avaluacions PISA) que la repetició recau sobretot en alumnes d’ambients socials desafavorits i només milloren els resultats en casos comptats.

Extret de “L’avaluació des d’una mirada inclusiva” en Avaluar és aprendre

Proposta d’utilització d’espais del centre per a millorar l’ús de les llengües

Quadre 6: Utilització d’espais del centre per a millorar l’ús de les llengües. Extret de la Guia per a l’elaboració del Projecte lingüístic de centre Servei d’Educació Plurilingüe.

ECOLOGISME LINGÜÍSTIC

La idea fonamental és la defensa de la diversitat lingüística. En aquest sentit, destaquen les aportacions de M. Carme Junyent, especialment en l’àmbit de l’ensenyament, centrades en el reconeixement, la visualització i la valoració de la diversitat (a escala global i local) i en una desconfiança crítica cap als mecanismes de la planificació basats en el poder de l’estat («l’estat, especialment en la seva concepció actual, ha estat la força que més ha jugat a favor de l’homogeneïtzació lingüística» (1998: 67)). Per a Junyent (1992: 10), «el futur del català no es pot deslligar del futur de totes les llengües i molt especialment de totes les amenaçades. La preservació del patrimoni lingüístic ha de ser global perquè sigui plausible». Cal construir un nou ordre lingüístic que trenqui el binomi un estat – una llengua.

En aquesta mateixa línia diversòfila trobem els treballs de Jesús Tusón, igualment amb una clara voluntat divulgativa (especialment, Tusón, 2004); també Comellas (2006); igualment, treballs com Projecte ecolingüística, de Bernat Joan, en aquest cas orientat cap a les polítiques d’àmbit europeu (Joan explota el paral·lelisme de llengües amenaçades i espècies en perill d’extinció). Cal recordar, també, que l’ecologisme lingüístic en el vessant d’acció cívica té un llarg recorregut en l’àmbit català, com ho demostren institucions com Ciemen o Linguapax. Els darrers anys, fins i tot s’ha creat una entitat governamental, Linguamón, que s’orienta clarament en aquesta direcció. També en l’àmbit acadèmic institucions com la Càtedra UNESCO de Llengües i Educació (dirigida per Joan A. Argenter), la Càtedra de Multilingüisme Linguamón-UOC (dirigida per Isidor Marí) o el Grup d’Estudis de Llengües Amenaçades (GELA) (dirigit per M. Carme Junyent) centren la seva recerca en la diversitat.

Informació extreta de Comellas Casanova, Pere. (2011) «Ecologia lingüística». Treballs de sociolingüística catalana, 21, p. 65-72.