Language usage level and statistics

2.3. USAGE AND STATISTICS

Legal

In Catalonia, País Valencià (Comunitat Valenciana) and the Balearic Islands, Catalan is present in the self-government status as the language of the territory and is the official language together with Castilian. Furthermore, in Catalonia, in the Aran Valley, it cohabits with Occitan, called Aranese, and also recognized as official language.

Image 7: Map of the Catalan linguistic spread from the web of Institut Ramon Llull. Què és el català i on es parla

Each regional parliament has approved specific linguistic laws:

- In Catalonia, Llei 1/1998, January 7th, about linguistic policy.

- In the Comunitat Valenciana, Llei 4/1983, November 23rd, regarding the use and teaching of Valencian.

- In the Balearic Islands, Llei 3/1986, April 29th, of linguistic normalization of the Balearic Islands.

- In the Western Strip, Llei 3/1999, March 10th, regarding Cultural Heritage of Aragon.

- In Northern Catalonia, the law regarding the use of French, Llei Toubon (1994).

- In Alguer, Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche (1999).

- In the Principality of Andorra, according to the Constitució de 1993 Catalan is the only official language.

Information from Institut Ramon Llull: Què és el català i on es parla

Regarding the acknowledgment to the European Union, some agreements have been established, according to which anyone can address the European Commission, the Council of Ministers or the Ombudsman in Catalan. Also, the European Parliament, in 1990, decided to include a Catalan version of the basic texts and resolutions of the EU.

The proposed concept is linguistic availability, understood as the possibility that the citizens have to use a territorial language in the public services at a state level, to assess if the States are fulfilling (or not) the national rules and the international political compromises that are binding of developing a linguistic policy regarding the different languages.

Beyond the Constitution, that includes five references to the State languages, but that regulates linguistic officiality only in article 3, there is a wide variety of dispositions that force the Administration and other public bodies to develop a linguistic policy that guarantees a public service in territorial languages beyond Castilian. These linguistic obligations stem both from the Supreme Court’s case law and from the national rules and regulations and the international political compromises ratified by the State.

The Spanish State can be distinguished by being of the most linguistically diverse States in Europe. Around 45% of the population lives in territories where a language different to Castilian Spanish is spoken. In eleven out of the seventeen regions of the State and in both autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla there are territorial languages present (Brohy et al., 2019). That does not mean that 45% of the population speaks a territorial language frequently, but that almost half of the State population lives in traditionally multilingual contexts. We must the consider as well immigration languages.

When we analyze the data, we see that in the State there are around thirteen million people (around 30% of the population) that talk a territorial language different to Castilian, while Castilian is spoken by around forty-six million people. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of territorial linguistic diversity.

ECMLR has an assessment tool that allows for a follow-up. A committee of independent experts writes periodical tracking reports on the degree of compliance of the obligations regarding territorial languages (so-called regional or minority in the reports). This is called a monitoring cycle. More than two decades after the ECMLR was ratified by the State, we still find systematic and continuous breaches in the obligations by the Administration, though they are legally binding. In Spain, the following languages are used: Amazigh, Ceutan Arabic, Aragonese, Asturian, Basque, Calo, Catalan/Valencian, Galician, Leonese and Portuguese. The situation of some of these languages is still to be defined, according to the Charter.

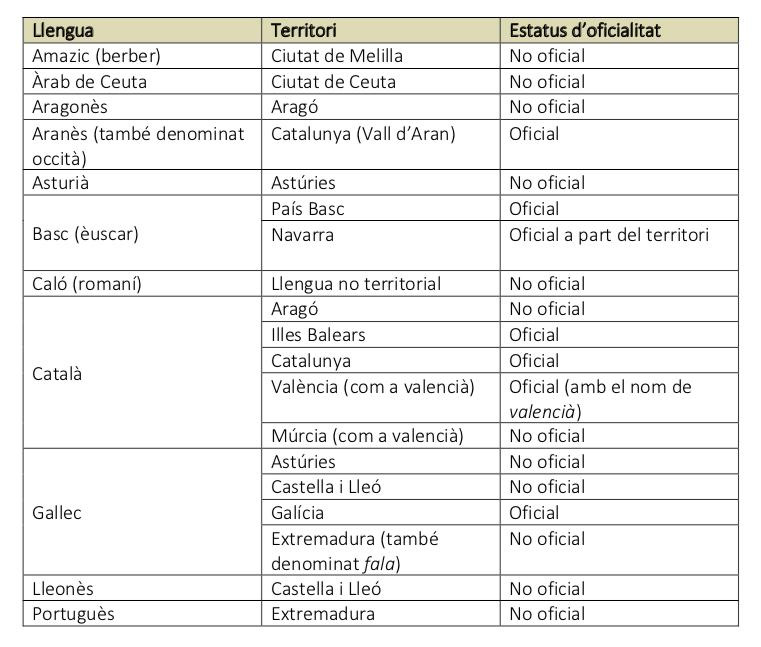

Chart 1. Languages, territories and officiality situation

Chart from Claudine BROHY, Vicent CLIMENT-FERRANDO Aleksandra OSZMIANSKA-PAGETT i Fernando RAMALLO (2919). Carta Europea de les llengües regionals o minoritàries. Activitats a l’aula. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

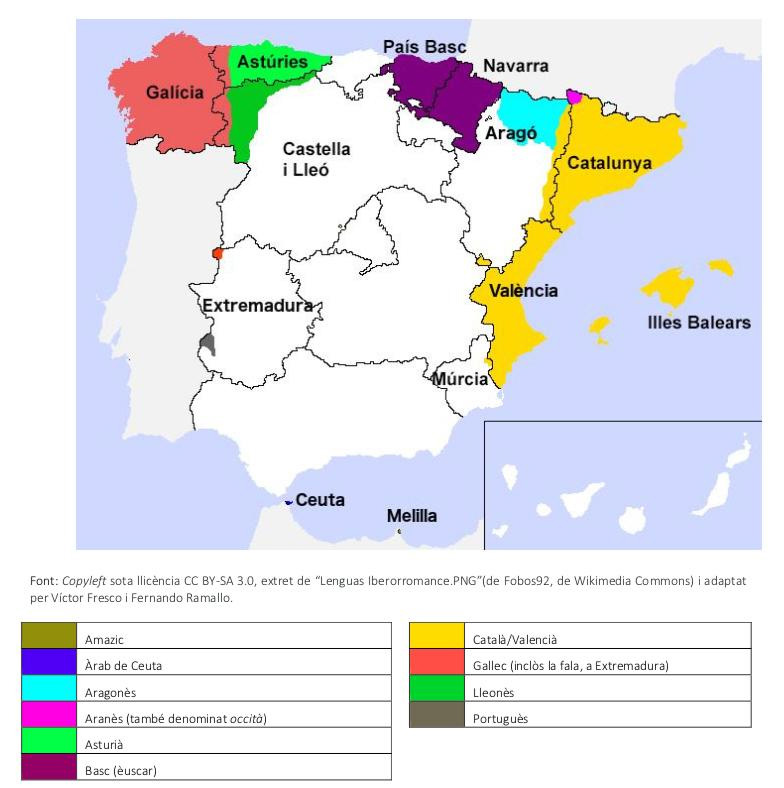

As we can see in the map below, minoritarian languages are spoken in eleven of the seventeen regions in Spain and in both autonomous cities, Ceuta, and Melilla. As a matter of fact, around 45% of the population in Spain lives in a territory with an indigenous minoritarian language. That does not mean that almost half of the Spanish population frequently speaks a minoritarian language, but that an important proportion of the population lives in a bilingual or monolingual context.

Image 8: The languages of the State (Adapted from Brohy et al., 2019)

International compromises of the State regarding co-official languages

In 2001, the State ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) of the Council of Europe, the only international legally binding tool devoted to the protection of the so-call regional or minority languages, after what the State is obliged to promote the territorial languages. Many authors consider the State ratification of the ECRML positively. As Climent Ferrando put it, “with the ECRML, regional or minority languages were integrated into the European political agenda. Until that moment, there was no international legal instrument devoted exclusively to these languages” (2018: 2). For the linguistic communities of the State, the ECRML “led to an initial optimism that allowed to advance towards a legal frame of linguistic pluralism in the State” (Castellà, 2018: 96).

State-EU bilateral agreements (2005-2009)

En 2004, the State signed the Memorandum for the acknowledgement in the European Union for all official languages in Spain. It demanded the acknowledgement of all the languages in the State within de EU in three fields: written communications from the citizens to institutions, oral interventions of political representatives, and the official publishing of Union texts. The State did not assume the derived costs (Mir, 2006; Pons-Parera, 2006). The State co-official languages did not become official in the EU. They were included in a new linguistic category, “additional languages.”

The creation of this “additional languages” category opened the door for the first time, albeit limitedly, to a real acknowledgment, through binding administration agreements, that went beyond the generical acknowledgment of the EU’s respect to linguistic diversity (Climent-Ferrando, 2016). In the period between 2005 and 2009, six agreements were signed with different institutions, as well as a proposal of linguistic uses in the European Parliament.

It is obvious that, while the linguistic availability of co-official languages seems appropriate as far as the oral usage in the Committee of Regions and the Council, we cannot state that the same happens with written linguistic usage, that are framed in what we call “symbolic politics,” giving a false sense of the development of linguistic policy in co-official languages in the EU.

The State still has not made available approvable and coherent data regarding the number of speakers of their languages and their territorial distribution. This lack of data has been repeatedly reported by experts of the Council of Europe and also by the reporter of the United Nations for minorities, that stresses that in every public policy, like the linguistic policy, it is key to have data available in order to apply the necessary steps: “Spain does not systematically collect disaggregated data on its population’s languages […]. This approach does not result in the precise information on the population that is necessary to design better-targeted, effective and evidenced-based government policies and programs.”

We have observed that there is a lack of real display of linguistic policies from the State, as we can see in the small number of public services fully offered in a co-official language or, in other words, a low linguistic availability. There is a lack of continuous political action, seen in the lack of actions from the public body that should be the one to deploy the State’s linguistic policy, the Council of Co-official languages. We have also established that the State has conceptualized multilingualism as a reality that is foreign to the State itself. Nevertheless, we also have to admit that there is a change in the trend, though reduced and only rhetorical, since the State, for the first time, admits the lack of action, of sensibility and of data, and gives then a series of recommendations. It remains to be seen if these intentions go beyond political rhetoric, and are translated into concrete actions, so that the languages of 30% of the population and 45% of the territory are conceptualized and considered from a state perspective. In short, the State must transition to the residual and symbolic management of its multilingualism towards a multilingualism conceptualization as a State policy.

Extract from “El multilingüisme: una qüestió d’Estat? L’avaluació de la política lingüística de l’Estat espanyol a través del concepte disponibilitat lingüística.” Vicent Climent-Ferrando Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Treballs de Sociolingüística Catalana, núm. 32 (2022), p. 53-80 DOI: 10.2436/20.2504.01.188 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/TSC

2.3. ÚS I ESTADÍSTIQUES

Marc legal

A Catalunya, al País Valencià (Comunitat Valenciana) i les Illes Balears, el català és declarat pels respectius estatus d’autonomia com a llengua pròpia del territori i hi és la llengua oficial juntament amb el castellà. A més, a Catalunya, a la Vall d’Aran conviu amb l’occità, que rep el nom d’aranès, també reconegut com a llengua oficial.

Què és el català i on es parla

Cada parlament autònom ha adoptat lleis lingüístiques específiques:

-

A Catalunya, la Llei 1/1998, de 7 de gener, de política lingüística.

-

A la Comunitat Valenciana, la Llei 4/1983, de 23 de novembre, d’ús i ensenyament de valencià.

-

A les Illes Balears, la Llei 3/1986, de 29 d’abril, de normalització lingüística de les Illes Balears.

-

A la Franja de Ponent, la Llei 3/1999, de 10 de març, del Patrimoni Cultural Aragonès.

-

A la Catalunya del Nord, la llei relativa a l’ús de la llengua francesa, Llei Toubon (1994).

-

A l’Alguer, Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche (1999).

-

Al Principat d’Andorra, d’acord amb la Constitució de 1993 el català és l’única llengua oficial.

Informació extreta de l’Institut Ramon Llull: Què és el català i on es parla

Pel que fa al reconeixement a la Unió Europea, s’han establert acords pels quals qualsevol persona es pot adreçar en català a la Comissió Europea, al Consell de Ministres o al Defensor del Poble en català. També, el Parlament Europeu l’any 1990 va resoldre incloure una versió catalana dels textos i resolucions fonamentals de la UE.

Es proposa el concepte disponibilitat lingüística —entès com la possibilitat de la ciutadania d’utilitzar una llengua territorial en els serveis públics estatals— per avaluar en quina mesura l’Estat (in)compleix les disposicions normatives nacionals i els compromisos polítics internacionals jurídicament vinculants de desplegar una política lingüística relativa a les llengües de l’Estat.

Més enllà de la Constitució, que inclou cinc referències a les llengües de l’Estat, però que regula l’oficialitat lingüística només a través de l’article 3, existeixen tot un seguit de disposicions jurídiques que obliguen l’Administració General de l’Estat (AGE) i els organismes públics a desenvolupar una política lingüística que garanteixi un servei públic en llengües territorials a banda del castellà. Aquestes obligacions lingüístiques provenen tant de la jurisprudència del Tribunal Constitucional com dels preceptes normatius nacionals i dels compromisos polítics internacionals ratificats per l’Estat.

L’Estat espanyol es caracteritza per ser un dels estats lingüísticament més diversos d’Europa. Al voltant del 45% de la població viu en un territori en què es parla una llengua territorial diferent del castellà. A onze de les disset comunitats autònomes de l’Estat i a les dues ciutats autònomes de Ceuta i Melilla es parlen llengües territorials (Brohy et al., 2019). Això no significa que el 45% de la població de l’Estat parle una llengua territorial de manera freqüent, sinó que gairebé la meitat de la població de l’Estat resideix en contextos tradicionalment multilingües. A això, caldria afegir-hi les llengües de la immigració.

L’anàlisi de les dades ens indica que a l’Estat hi ha aproximadament tretze milions de persones —un 30% de la població total— que parlen una llengua territorial diferent del castellà, mentre que el castellà és parlat per uns quaranta-sis milions de persones. La figura 1 il·lustra la distribució de la diversitat lingüística territorial.

La CELRoM disposa d’un instrument d’avaluació que permet fer-ne el seguiment. Un comitè d’experts independents redacta els informes de seguiment periòdics sobre el grau de compliment de les obligacions en matèria de llengües territorials (anomenades regionals o minoritàries als informes). És el que es coneix com a cicle de seguiment. Més de dues dècades després de la ratificació per part de l’Estat de la CELRoM, es detecten encara incompliments sistemàtics i continuats en les obligacions a l’AGE, que són jurídicament vinculants. A Espanya s’usen les següents llengües: amazic, àrab de Ceuta, aragonès, aranès, asturià, basc, caló, català/valencià, gallec, lleonès i portuguès. La situació d’algunes d’aquestes llengües segons la Carta encara està per definir.

Quadre extret de Claudine BROHY, Vicent CLIMENT-FERRANDO Aleksandra OSZMIANSKA-PAGETT i Fernando RAMALLO (2919). Carta Europea de les llengües regionals o minoritàries. Activitats a l’aula. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

Com es pot observar al mapa següent, les llengües minoritàries es parlen en onze de les disset comunitats autònomes d’Espanya, i en les dues ciutats autònomes de Ceuta i Melilla. De fet, al voltant del 45% de la població a Espanya viu en un territori en el qual es parla una llengua minoritària autòctona. Això no vol dir pas que quasi la meitat de la població d’Espanya parli una llengua minoritària de manera freqüent; tanmateix, indica que un percentatge destacable de la població es troba en un context bilingüe o monolingüe d’una manera o d’una altra.

Els compromisos internacionals de l’Estat respecte a les llengües cooficials

El 2001, l’Estat ratificava la Carta Europea de Llengües Regionals o Minoritàries (CELRoM) del Consell d’Europa, l’únic instrument internacional jurídicament vinculant dedicat a la protecció de les llengües dites regionals o minoritàries a partir del qual l’Estat es compromet a promoure les llengües territorials de l’Estat. Són nombrosos els autors que consideren positiva19 la ratificació estatal de la CELRoM. Tal com afirma Climent-Ferrando, «amb la CELRoM, les llengües regionals i minoritàries passaven a formar part de l’agenda política europea. No existia fins aleshores cap instrument jurídic internacional exclusiu relatiu a aquestes llengües» (2018: 2). Per a les comunitats lingüístiques de l’Estat, la CELRoM «suposà un inicial optimisme per avançar cap a un règim jurídic de pluralisme lingüístic a l’Estat» (Castellà, 2018: 96).

Els acords bilaterals Estat-UE (2005-2009)

El 2004, l’Estat signava el Memoràndum per al reconeixement a la Unió Europea de totes les llengües oficials a Espanya, a través del qual demanava el reconeixement de les llengües de l’Estat a la UE en tres àrees: les comunicacions escrites dels ciutadans amb les institucions, les intervencions orals dels representants polítics i la publicació oficial dels textos comunitaris. L’Estat n’assumiria els costos derivats (Mir, 2006; Pons-Parera, 2006). Les llengües cooficials de l’Estat no passaven a ser oficials a la Unió Europea, sinó que eren catalogades amb una nova categoria lingüística: «llengües addicionals».

El fet de crear la categoria «llengües addicionals» obria la porta per primera vegada, tot i que de manera limitada, a un reconeixement efectiu, palès a través d’acords administratius vinculants, que anaven més enllà de reconeixements genèrics europeus sobre el respecte de la UE a la diversitat lingüística (Climent-Ferrando, 2016). Durant el període 2005-2009, es van signar sis acords amb diferents institucions, juntament amb una proposta d’usos lingüístics al Parlament Europeu.

Es constata que mentre que la disponibilitat lingüística de les llengües cooficials sembla adequada pel que fa als usos orals al Comitè de les Regions i al Consell, no podem afirmar el mateix dels usos lingüístics escrits, que s’emmarquen més en el que anomenaríem symbolic politics, en la falsa impressió de desenvolupament d’una política lingüística de les llengües cooficials a la UE.

L’Estat continua sense disposar de dades homologables i coherents sobre el nombre de parlants de les seves llengües o sobre la distribució territorial. Aquesta manca de dades ha estat denunciada repetidament pels experts del Consell d’Europa i també pel relator de les Nacions Unides per a les minories, que posa l’èmfasi que en qualsevol política pública —com és la política lingüística— és crucial disposar de dades per poder adoptar les mesures necessàries: «Spain does not systematically collect disaggregated data on its population’s languages […]. This approach does not result in the precise information on the population that is necessary to design better-targeted, effective and evidenced-based government policies and programmes».

Hem observat una manca de desplegament real de la política lingüística de l’Estat, evidenciat amb la baixa xifra de serveis públics oferts plenament en una llengua cooficial, o, dit en d’altres paraules, una baixa disponibilitat lingüística; hem detectat una manca d’acció política continuada en el temps, evidenciada amb l’absència d’accions per part de l’entitat pública destinada precisament a desplegar la política lingüística de l’Estat, el Consell de les Llengües Cooficials, i hem constatat l’existència d’una conceptualització del multilingüisme per part del mateix Estat com a realitat aliena al mateix Estat. Amb tot, cal dir que observem un cert canvi de tendència —encara prudent, emmarcat en el camp retòric— en què, per primera vegada, l’Estat reconeix la manca d’acció, de sensibilització i de dades i proposa un seguit de recomanacions. Caldrà analitzar si aquestes intencionalitats van més enllà de la retòrica política i es tradueixen en accions concretes perquè les llengües del 30% de la població i del 45% del territori passin a ser conceptualitzades i tractades des d’una òptica estatal. En definitiva, perquè l’Estat faci la transició de la gestió residual i simbòlica del seu propi multilingüisme cap a una conceptualització del multilingüisme com a política de l’Estat.

Extret de “El multilingüisme: una qüestió d’Estat? L’avaluació de la política lingüística de l’Estat espanyol a través del concepte disponibilitat lingüística”. Vicent Climent-Ferrando Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Treballs de Sociolingüística Catalana, núm. 32 (2022), p. 53-80 DOI: 10.2436/20.2504.01.188 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/TSC