The minoritized language as a mechanism of inclusion

«Everyone is entitled to receive an education in the language proper to the territory where he/she resides» (Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights, Article 29/1)

An old legend says that a long time ago, there was a king who heard that in his country there lived a truly wise man. He was so wise, they said, that he could speak all the languages in the world. He knew the song of the birds and understood it as if he were one of them. He knew how to read the shape of the clouds and immediately understand their meaning. Any language he listened to, he could answer

without hesitation. He could even read the thoughts of men and women wherever they came from. The king, impressed by all the qualities that were attributed to him, called him to his palace. And the wise man came.

When he was there, the king asked him:

“Wise man, is it true that you know all the languages of the world?”

“Yes, Sir,” was the answer.

“Is it true that that you listen to the birds, and you can understand their song?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“That you know how to read the shape of the clouds?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“And, as I have been told, that you can even read people’s minds?”

“Yes, Sir.”

The king still had a last question…

The king looked at him as if defying him, as if testing him, and asked him the final question:

“In my hands, which are hidden behind my back, there is a bird. Wise man, answer me: is it alive or dead?”

The answer of the wise man was addressed to everybody. In our case, to everybody who has any responsibility in promoting linguistic rights, from the activist to the writer, from the teacher to the legislator. For that wise man, surprisingly, felt scared. He knew that, whatever the answer, the king could kill the bird. He looked at the king and remained silent for a long time. Finally, in a very serene voice he said,

“The answer, Sir, is in your hands.”

The wise man’s answer is for everyone. In our case, anyone who has responsibility in the promotion of linguistic rights, from militants to writers, from teachers to legislators.

The answer is in our hands.

Extracted from the Preface, by Carles Torner i Pifarré from the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights

Published by Multillengües.

4.1. THE MINORITARIAN LANGUAGE AS AN INCLUSION MECHANISM

Inclusive education evolved from Special Needs Education and its philosophy to counterbalance the exclusion and discrimination of children with disabilities. In a wider context, this debate only used the label “integration” to refer to groups with learning disadvantages, such as migrants, cultural and linguistic minorities, children or adults from a lower economic or social class, etc.

The debate concerning the educational reform and change that were needed to achieve a quality education for everybody have shown that the diversity challenge cannot be reduced to integrating a marginalized group of people. Rather, everyone must pursue and work towards the common objective of finding a holistic goal that guarantees equal opportunities and rights for everyone.

In this context, inclusive approaches are launched as a way of creating learning environments that allow learning processes, results and democratic, effective and sustainable results for everyone.

Plurilingual education and the resulting pedagogical approaches aim to respect and develop the linguistic repertoire of each student, so that they can use languages with different degrees of competence and adapted to different contexts (home, school, public, private, professional, etc.).

The concept of plurilingualism appeared for the first time within the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001). The approach was that the implementation of a plurilingual education would have a deep impact on the linguistic education, since it would foster a change from the ideal of “dominating” a foreign language to the perspective of developing linguistic abilities and competences that are unique to each student.

In the debate regarding quality education for everyone, the social aspect of plurilingual education has been pointed out. The awareness-raising activities towards the languages present in the classroom, but that are only seldom considered learning tools, are now considered as a powerful means to develop the learning among peers based on tolerance, respect, and knowing each other. Considering this dimension, plurilingual education is the perfect complement for the inclusive and intercultural components of the foreseen pedagogical focus.

T

LANGUAGES IN TEACHING

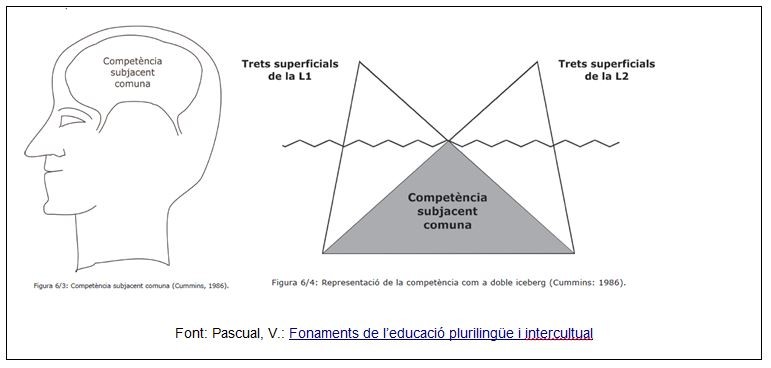

Plurilingual competence is not the result of adding competences in more than one language, but a different skill that allows people to use the linguistic repertoire of all the languages they know depending on their communicational needs. Until de 1970s, competence in different languages was considered to have to be gained separately, as if the brain had different warehouses for each of the languages. They also thought that teaching in an L2 was a disadvantage for the student. These conceptions defined the learning methods for second languages.

The approach changed when Cummins (1979) developed the “hypothesis for interdependent development,” according to which some skills in the use of languages, once the skills for Language A have already been developed, do not need to be learnt again to acquire the use of Language B, when this latter one is acquired afterwards. Hence, children with a development of the L1 did not have any difficulties in accessing immersion programs. Therefore, the success in bilingual education programs depends on the competence level acquired in the L1 by the children when they are first integrated in school.

Furthermore, Cummins talks about an educational approach, that is, the teachers’ attitude regarding linguistic skills for students and the expectations created regarding their linguistic learning, as key factors to turn the introduction of a second language into a positive experience.

Information extracted from Guasch, O. (2011): Les llengües en l’ensenyament. En Camps, A. (coord.). Llengua catalana i literatura. Complements de formació disciplinària. Graó.

To manage the citizens’ social multilingualism, there are certain challenges that need to be solved:

-

Regarding the plurilingualism among natives, it is necessary to review teaching practices to avoid that teaching languages in an endless loop of repetitions and badly-learnt concepts.

-

Regarding plurilingualism among non-natives, it is necessary to develop Catalan promotion policies, to give the right value to arriving languages, at least as far as the Administration can, and to assume that some segments of society will not integrate linguistically (tourists, immigrants on transit, elderly people, etc.)

Finally, these and other challenges can only be undertaken in the frame of a project that complies with two general condition. On one hand, it must be socially fair, that is, to consider that languages are above all a cultural capital that promotes social progress. Therefore, linguistic policies must be able to combine the objective towards social cohesion, resource distribution and the acknowledgement of differences. On the other hand, any linguistic policy that hopes to be successful must be sociolinguistically realistic. The history of linguistic policies is full of cases that show that when regulating the linguistic reality of a country it is as important to not be hasty as it is to avoid the temptation, almost inevitable among those who suffer, to get carried away by hopes and wishes.

Extracted from: Vila, F. X. (2016) Sobre la vigència de la sociolingüística del conflicte i la noció de normalitat lingüística. Treballs de Sociolingüística Catalana, núm. 26 , p. 199-217 DOI: 10.2436/20.2504.01.116 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/TSC

PLURILINGUAL COMPETENCES IN SCHOOL

When someone enters a school or high school, they must do so with their whole background, personal, cultural and linguistic. Once they are inside, we must pay attention to this background, because it is the basis on which we can build the learning process. There was a metaphor about this idea that clarifies a lot. The metaphor used –and still uses– the terms submersion and immersion. To submerge is to place under, while to immerse is to place inside. Submersion hides, immersion contextualizes. In the music classroom, on leaflets, when we consider what festivities we celebrate, etc., we cannot ignore the linguistic and cultural reality present in our school. Languages, just like cultures, must be visible, must be breathed in as soon as we enter the door.

Creating links is, in a way, protecting each other, filling out the empty space that exists between my world and worlds I know little about beyond mere stereotypes. There is no doubt that this emptiness must be filled with words, but also with what we know as sympathy, the ability to look for the space where experiences and feelings meet. Approaching others without allowing prejudices to blind you, with the will to break possible asymmetries that might exist, because they speak different from me, because they are not from here, because they do not know our habits, etc. Creating links implies what some authors call “de-centralizing oneself.” Others call it “expose oneself to difference.” And there are some who call it “reducing social distance.” We must be capable to go beyond ourselves and the way me and my people think and live in the world, so that we can join and get involved in a collective space. Creating links, because everyone needs to feel respected by the law, valued by society and loved by the group.

Learning through contrast. Contrast, navigating between cultures and languages to learn, is not something we link to superposition, occasional actions, or impositions, but to a stimulus for personal growth. The difference is not an anecdote. The difference must be recognized in its identity and validity. It is right in this that speeches who talk about tolerance differ from those who aim towards plurilingualism. Tolerance is a concession and, hence, the approach is unidirectional; plurilingualism is acknowledgement, and there the approach is in both directions: the kid feels looked at by his teacher, and the teacher feels the eyes of the kid, eyes that demand comprehension. In the frame of plurilingual education, nothing and no one is alien, because there is a constant shift between all manners of feeling, doing and saying. Learning through contrast, because, when knowledge travel to unknown places, it is never the same upon its return.

Information extracted from: Palou Sangrà, J. i Fons Esteve, M. (coord.) (2019). La competencia plurilingüe a l’escola. Experiències i reflexions. Octaedro. https://octaedro.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/80184.pdf

We live in an increasingly multilingual and multicultural society, and schools must mirror this diversity. The challenge of plurilingual education is huge: to teach plurilingual people making sure that their education includes a minority language.

We can say that languages and cultures that are present in school were not taken into consideration. On the contrary, there is as separation between school content and linguistic areas, which provokes, for example, the repetition of concepts and the terminology variations regarding the same terms depending on diverse grammar traditions or theoretical reference frameworks. The plurilingual reality demands approaching metalinguistic reflection in a linked manner, comparing different phenomena depending on the languages spoken by the students. An integral approach to the languages to be learnt is a must so that linguistic theory can be treated as a whole towards improving educational techniques. This linguistic situation in schools should also be a taken as a chance to teach and learn, in general, and to teach and learn languages, in particular.

Linguistic borders do not often match territorial borders. As a matter of fact, multilingualism is frequent. It is strange to find a state where they only speak one language. The existence of a state with only one language is an exception, the most frequent situation being that diverse linguistic communities cohabitate inside a state. That has driven the different states to adopt different linguistic policies, aimed towards promoting the use of the chosen official language and erase all the other, or promote the use of all languages.

According to Nicolás (2021), in language didactics it is advisable to use neutral terms, with less connotations than native language, such as familiar language or first language(L1), in contraposition to second language or acquired language (L2). Furthermore, in the language teaching field in a plurilingual context and with territories with due official languages, as Bataller (2019) points outs, there is a difference between L1 and L2, that have an official status, and FL, with no official status. In our particular sociolinguistic situation, there is an obvious difference between what we define as second languages. While some are truly foreign languages (English, French, etc.), Catalan or Castilian, depending on the case, are languages that are present, in a broader or smaller degree, among our students, even if one, and only one, is their first language, and, from those two, only one, Catalan, is the language of their country. We must add that, instead of using the term foreign language (FL), we use the term additional language (AL), which is the one we learn after acquiring speech through our first language.

Linguistic and cultural diversity, so definitory of the 21st century, has driven the interest in learning languages in multilingual contexts. Boix and Vila (1998) consider monolinguistic the model used by states that choose a single variety as national language. They believe there are other two models: the plurilingual model, that accepts in different degrees the citizens’ linguistic diversity, and the control model, that allows subordinate groups a changing degree of collective autonomy, with a delegation of linguistic policies, but always within the limits marked by the dominant group, so that the subordinate group needs to adapt its values and rules to the majoritarian one.

The linguistic immersion program is an educational model that partakes in the so-called enrichment models (Fishman, 1976) and that is a totally bilingual program. Etymologically, the word immersion is related to swimming, to completely surround oneself with water and, in this case, to completely surround oneself, in a natural, specific and controlled manner, with the language that one wants to learn, to make one’s own. It is the acquisition of a new language in special circumstances, that do not oppose the 1928 principles of the Luxembourg Office or the UNESCO principles. Linguistic immersion is not a reaction to the destruction of a language. Rather, it aims for a greater equality and, especially, a means of possessing – or giving the means to possess – a language that was previously alien, totally or partially.

It is an L2 learning program, aimed for the students within the majoritarian language and culture .Its objectives are bilingualism and biculturalism. The students keep L1 because of the way it is treated in school and for the support and status it has outside the school, but learn L2 through a natural, non-forced process, using the language as a learning tool in the different subjects. These programs have a high degree of success, because academic success is equivalent to the one achieved by students learning in the L2, but they acquire a better competence in L2. They promote added bilingualism because it, to the knowledge of their own language and culture, they add another one.

According to the Plurilingualism Law, teachers must adapt their teaching programs to the goals defined by the Center’s Linguistic Project (CLP), using integral language and content learning, plural approaches or active methodologies as the methodological reference that prioritizes the students’ role, that must be placed in the heart of the educational process, while promoting the use of the language.

Information extracted from Martí Climent, A. (2022). Projecte docent. Desenvolupament d’habilitats comunicatives en contextos multilingües. UV.

MODELS AND DIDACTICAL INTERVENTION

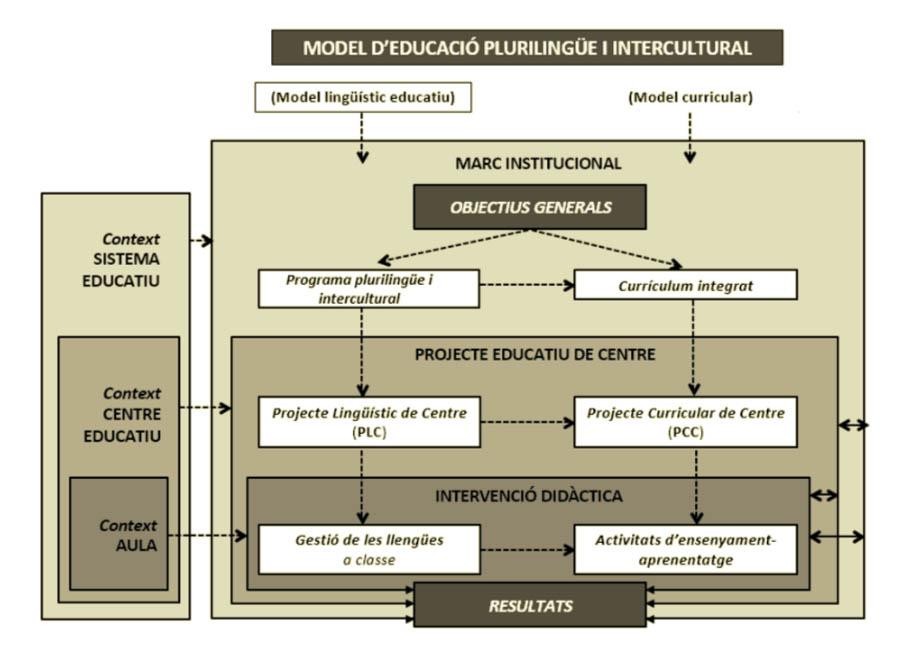

As we saw in the plurilingual and intercultural teaching model, the education system has three levels: the Institutional Framework, that establishes the objectives, the organization in just one plurilingual and intercultural program, and the official integrated curriculum; the Center’s educational project, through which the teachers, within the limits defined by the Institutional Framework, organize the teaching and the teaching use of languages, the normalization of the social and institutional uses of Valencian, and the promotion of Valencian in the relationship with parents and the environment; and the Didactic Intervention in the classroom, that manages the use of languages in class, and the planification and execution of the learning and teaching activities.

The results of the educational system, therefore, do not depend only on the Didactical Intervention, that is, on the work in class that teachers and students do, but also on the joint influence of the different levels. Any attempt to assess the students’ performance must consider them all, and analyze each level’s influence in the results.

Figure 1: Structure of the Plurilingual and Intercultural Educational Model (Baldaquí i Pascual, 2021)

Beyond the forecasts of a plurilingual learning program, what is important is how we apply it, that is, how it really reflects in the classrooms. In truth, it is the classroom teachers that must face the most complex problems: the need to teach the same curriculum to a diverse group of students, the attitude, that more or less negative attitude of the families and the students towards the use of the minoritarian language as a teaching and learning tool, the lack of knowledge of the teaching languages by part of the students, the inappropriate teaching materials for a plurilingual teaching, etc. And always taking inclusion into consideration, trying that each student achieves their full potential regardless of their starting point. To allow that, in these circumstances, this group of heterogeneous students reaches their curricular goals and that they become aware of the advantages and possibilities that knowing Valencian might mean, that they acquire optimal competences, and that it states their will to communicate normally in this language, whether it is their L1 or not, implies making decisions in two fields, in the language management in the classroom and in the didactic planning and actions.

In order to achieve the objectives of the Plurilingualism Law, Baldaquí and Pascual (2021) propose an educational plurilingual and intercultural model that is self-centered, a model of bare minimums to advance in the construction of a Valencian school that must:

a) turn Valencian into the core of the linguistic and learning planning;

b) adopt a particular perspective, a Valencian one, on the curriculum;

and c) promote favorable attitudes towards Valencian and its use as a the daily language.

Information extracted from Baldaquí, J. M. i Pasqual, V. (2021). Gestió de les llengües en entorns educatius multilingües: una perspectiva valenciana. Revista de Llengua i Dret, Journal of Language of Law, 75, 64-84. https://doi.org/10.2436/rld.i75.2021.3588

TOWARDS A COMPTENCE-ORIENTED LEARNING OF ADDITIONAL LANGUAGES

The approach in additional languages didactics that is on the base of the Common European Framework of Reference defends the need to formulate learning objectives regarding competences. Competences specify what students must be capable to do when they complete the different phases of the learning process.

In this approach, the new methodologies put the learning in the center of the process, instead of the learning subjects, while they place the students as the main character and responsible for their own process. From this point of view, we must emphasize the need to understand the learning of the additional language as capacitation, instead of understanding it only as instruction.

The promotion of plurilingual competence becomes key, because it refers to the ability – inherent to all bilingual and plurilingual speakers – to interlink languages: the individual does not stack these languages and cultures in different drawers, in airtight containers. On the contrary, they develop communicational competences that are fostered by all linguistic knowledge and experiences. Languages relate to one and other and interact in the students’ mind.

Information extracted from: Esteve, O.; Vilà, M. (2018): Cap a l’aprenentatge competencial de llengües addicionals. Articles de Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura. 78. Graó.

In order to interpret both the advances and the difficulties of the students who are learning and in order to furnish a customized learning experience, teachers should consider the particularities of the learning process of an additional language in an academic context:

- Complex: has abundant intermediate processes, several routes and causes.

- Gradual: it implies to fit in shapes, meanings and uses.

- Non-lineal: when the acquired knowledge is restructured, there are falls and moments of apparent standstills.

- Dynamic: learning factors and strategies change during the process.

- Non-influenceable: students learn certain contents when they are ready for them, that is, in a particular stage of their learning.

- Irregular: not everyone learns at the same speed or reaches the same level.

- Social: interactions between L1 and L2 speakers or those between L2 speakers are key to develop the learning process.

- Mobilization of previous knowledge and experiences: learners formulate, more or less consciously, hypothesis of how to articulate what they want to say and they check them with they interact with other speakers.

- Open to improvement through the appropriate educational action: students who receive a formal learning in the language and engage in thinking and interaction process that are controlled do not fossilize wrong versions of their interlanguage. Rather, they can evolve towards an acquisition of L2. It is important to point out that, according to research, the systematic and immediate correction does not seem productive at all. We must avoid working the language following morphological lists and paradigms, and, on the contrary, must articulate significant and contextualized activities in broad didactic processes and that make sense for the speakers.

These particular characteristics of the initial learning of a language must not lose sight that, even if specific supports are needed, it is also key that the students participate in standard classrooms from the first moment and advance to learn both languages and contents in areas and subjects.

Information extracted from ADCL – Didàctica del català com a segona llengua per a l’alumnat nouvingut. Gencat.cat

EDUCATION IS A CONVERSATION

In education we assist every day to a conversation between the school culture and the students’ culture, between the world of adulthood and the world of childhood, adolescence, and youth. For this reason and with the object to make sure that this conversation does not turn into a monologue by teachers, it is convenient that academical culture (the curriculum and especially the activities that are performed in the classroom) opens to the analysis and reflection on the reference cultures of children present in pedagogical institutions and, therefore, takes into consideration of languages, cultural habits and the ways in which language is used, turning education into an intercultural dialogue between teachers and students, where learning would be built with what they already know, what they can already do and who they are when they come into the classroom.

The language pedagogy must be able to conjugate the estimation of linguistic diversity in the classroom (languages, register, styles, sociolects, geographical dialects…) and the criticism to cultural prejudices that are often observed in some languages, their speakers and their uses (especially regarding languages and the uses that the students with the native language in unfavorable and vulnerable environments). The goal is to allow children to become familiar with other ways of talking, with other oral and written genres, with other language registers, with other communicative environments and with other cultures that are alien to their daily environment, so that they can ensure the right that students have to know how to do other things with words in changing communicational situations.

COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE AND CULTURAL CAPITAL

Linguistic education must foster the communicational emancipation of the students, that is, their communicational competence to promote the use of the right language levels depending on each context and communicational situations (including public contexts or formal interaction situations), without underestimating the original ways of speech, that are absolutely legitimate, consistent and efficient in their informal and familiar environments. Only as long as the ways they use the language are valued and loved in the classroom, with no prejudices or contempt (and no normative obsession), students will understand the sese of what they are learning through the contrast between their daily uses of the language and the social uses of the languages that are a must in other contexts, different form the family and cultural environment they live in. In the end, communicational competence is not only the main objective of linguistic education. It is also, and foremost, a cultural capital of undeniable value in our societies.

Information extracted from: Lomas, C.; Jurado, F. (2021): Llengua de l’alumnat, llengua de l’escola. Articles de Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura. 91. Graó.

«Tota persona té dret a rebre l’ensenyament en la llengua pròpia del territori on resideix» (Declaració Universal de Drets lingüístics, Article 29/1)

Conta una antiga llegenda que, temps era temps, hi havia un rei que va sentir dir que al seu país vivia un savi autèntic. Tan savi, deien els rumors, que parlava tots els llenguatges del món. Sabia escoltar el cant dels ocells i els entenia com si fos un d’ells. Sabia llegir la forma dels núvols i comprendre immediatament el seu sentit. Qualsevol llengua que sentís, responia sense vacil·lar. Fins i tot llegia el pensament dels homes i les dones vinguessin d’on vinguessin.

El rei, impressionat per tants mèrits com se li atribuïen, va fer cridar aquell home savi al seu palau. I el savi hi va fer cap.

En tenir-lo al davant, el rei s’afanyà a preguntar-li:

–És cert, bon home, que sabeu totes les llengües del món?

–Sí, Majestat –va ser la resposta.

–És cert que escolteu els ocells i n’enteneu el cant?

–Sí, Majestat.

–Que sabeu llegir la forma dels núvols?

–Sí, Majestat.

–I, tal com m’han dit, és cert que fins i tot llegiu el pensament de les persones?

–Sí, Majestat.

El rei encara tenia una última pregunta…

El rei va mirar-lo desafiadorament, com si el volgués posar a prova, i li llançà l’última pregunta:

–A les meves mans, que tinc ara amagades a l’esquena, hi tinc un ocell, home savi. Respon-me: és viu o és mort?

Aquell savi, de forma inesperada, va tenir por. Sabia prou bé que, fos quina fos la seva resposta, el rei podia matar l’ocell. Va mirar el rei i s’estigué en silenci una llarga estona. Al capdavall, amb veu molt serena, va dir:

–La resposta, Majestat, és a les vostres mans.

La resposta del savi s’adreça a tothom. En el nostre cas, a tothom que tingui cap responsabilitat en la promoció dels drets lingüístics, des del militant fins a l’escriptor, des de la mestra fins al legislador.

La resposta és a les nostres mans.

Extret del pròleg de Carles Torner i Pifarré de la Declaració Universal de Drets Lingüístics

Publicat per Multillengües.

4.1. LA LLENGUA MINORITZADA COM A MECANISME D’INCLUSIÓ

L’educació inclusiva va evolucionar a partir de les Necessitats Educatives Especials i la seua filosofia per contrarestar l’exclusió i la discriminació dels nens amb discapacitat. En un context més ampli, aquest debat es va plantejar sota l’etiqueta “integració” dirigit a altres grups d’aprenentatge desfavorits com els migrants, les minories culturals i lingüístiques, els nens o adults de baix estatus econòmic o social, etc.

Les discussions sobre la reforma i el canvi de l’educació necessàries per aconseguir una educació de qualitat per a tothom han deixat clar que el repte de la diversitat no es pot fer front només amb els esforços d’integració del col·lectiu marginat. Més aviat, tots han de perseguir i treballar cap a l’objectiu comú d’adoptar un enfocament holístic que garanteixi la igualtat d’oportunitats i drets per a tothom.

En aquest context, s’estan promovent enfocaments inclusius com una manera de proporcionar entorns d’aprenentatge que permetin processos d’aprenentatge, resultats i resultats democràtics, efectius i sostenibles en benefici de tots.

L’educació plurilingüe i els plantejaments pedagògics resultants tenen com a objectiu respectar i desenvolupar el repertori lingüístic de cada aprenent que permeta al parlant utilitzar llengües amb diferents graus de competència i adaptades als diferents contextos (casa, escola, públic, privat, professional, etc.).

El concepte de plurilingüisme es va elaborar per primera vegada en el Marc europeu comú de referència per a les llengües (Consell d’Europa, 2001). Es va assenyalar que la implantació de l’educació plurilingüe tindria un impacte profund en l’educació lingüística en passar de l’ideal de “dominar” una llengua estrangera a la perspectiva de desenvolupar les habilitats i competències lingüístiques individuals úniques de l’aprenent.

En el context de la discussió sobre l’educació de qualitat per a tothom s’ha destacat l’aspecte social de l’educació plurilingüe. Les activitats de conscienciació dirigides a les llengües presents a les aules però que normalment no es consideren objectes d’aprenentatge s’estan considerant com un mitjà potent per desenvolupar l’aprenentatge entre iguals basat en la tolerància, el respecte i el coneixement mutu. En vista d’aquesta dimensió, l’educació plurilingüe complementa idealment els components inclusius i interculturals dels plantejaments pedagògics previstos.

La necessitat que els ciutadans europeus desenvolupen competències interculturals ha estat àmpliament reconeguda per les autoritats educatives i els professionals de l’ensenyament. En el Llibre blanc del Consell d’Europa sobre el diàleg intercultural (2008) s’assenyala que les actituds, el comportament, els coneixements i les habilitats rellevants en contextos interculturals no s’adquireixen com a efecte secundari del desenvolupament de les competències lingüístiques, sinó que s’han de situar explícitament en el context educatiu.

LES LLENGÜES EN L’ENSENYAMENT

La competència plurilingüe no és la suma de la competència en més d’una llengua, sinó una capacitat diferent que permet a les persones utilitzar el repertori lingüístic de totes les llengües que coneixen segons les seves necessitats comunicatives. Fins als anys setanta es considerava que la competència en diverses llengües s’havia d’assolir per separat, com si en el cervell hi hagués magatzems separats per a cadascuna de les llengües. També semblava que escolaritzar-se en una L2 representava un desavantatge per a l’alumne. Aquestes concepcions determinaven els mètodes d’aprenentatge de segones llengües.

El plantejament va canviar quan Cummins (1979) va elaborar la “hipòtesi del desenvolupament interdependent”, segons la qual algunes habilitats d’ús de les llengües, una vegada s’han desenvolupat en una llengua A, no han de ser apreses de nou per a l’ús d’una llengua B, adquirida amb posterioritat a la primera. Així, els nens i les nenes amb un desenvolupament de la L1 no tenien cap dificultat per a accedir als programes d’immersió. Per tant, l’èxit dels programes d’educació bilingüe està en funció del nivell de competència desenvolupat en la L1 pels escolars en el moment d’iniciar l’escolarització.

A més, Cummins es refereix al tractament educatiu, és a dir, a l’actitud del professorat respecte dels coneixements lingüístics dels alumnes i a les expectatives que es creen respecte del seu aprenentatge lingüístic com a factors claus perquè la introducció d’una segona llengua siga positiva.

Informació extreta de Guasch, O. (2011): Les llengües en l’ensenyament. En Camps, A. (coord.). Llengua catalana i literatura. Complements de formació disciplinària. Graó.

A l’hora de gestionar el multilingüisme social de la ciutadania, hi ha certs reptes que caldrà anar resolent:

-

Pel que fa a la plurilingüització dels autòctons, caldrà revisar en profunditat les pràctiques docents per evitar que l’ensenyament d’idiomes sigui un bucle inacabable de repeticions i lliçons mal apreses.

-

Pel que fa al plurilingüisme d’origen exogen, caldrà desenvolupar polítiques de difusió de la llengua catalana, atorgar una valoració a les llengües nouvingudes, almenys en el terreny competència de l’administració, i assumir el fet que uns segments de la població mai no s’integraran lingüísticament (turistes, immigrants passavolants, al·loglots de més edat, etc.).

Per acabar, aquests i altres reptes només es podran emprendre en el marc d’un projecte que compleixi dues condicions generals. D’una banda, que sigui socialment just, és a dir, que tingui molt present que les llengües són abans que res un capital cultural que permet el progrés social. En aquest sentit, les polítiques lingüístiques han de saber combinar l’objectiu de la cohesió social, la distribució dels recursos i el reconeixement de les diferències. De l’altra, qualsevol política lingüística que vulgui tenir expectatives d’èxit hauria de ser sociolingüísticament realista. La història de la política lingüística és farcida de casos que mostren que, a l’hora de regular la realitat lingüística d’un país, tan important és ser agosarat com evitar la temptació, tal vegada inevitable entre els llenguaferits, de deixar-se portar per les il·lusions i els desitjos.

Extret de: Vila, F. X. (2016) Sobre la vigència de la sociolingüística del conflicte i la noció de normalitat lingüística. Treballs de Sociolingüística Catalana, núm. 26 , p. 199-217 DOI: 10.2436/20.2504.01.116 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/TSC

LA COMPETÈNCIA PLURILINGÜE A L’ESCOLA

Quan algú entra per la porta de l’escola o de l’institut ha de fer-ho amb tot el seu bagatge, el personal, el cultural i el lingüístic. Un cop dins, hem de mostrar-nos atents a aquest bagatge, perquè és el fonament sobre el qual ha de transcórrer el procés d’aprendre. Hi havia una metàfora relacionada amb aquesta idea que era molt aclaridora. La metàfora usava –i usa, encara– els termes de submersió i d’immersió. Submergir és posar a sota; en canvi, immergir és situar a dins. La submersió amaga, la immersió contextualitza. A l’aula de música, als fulls informatius, a l’hora de pensar quines festes se celebren, etc., no podem ofegar la realitat lingüística i cultural present en el centre educatiu. Les llengües, així com les cultures, s’han de poder veure, s’han de poder respirar tan bon punt s’ha traspassat la porta.

Crear vincles és, d’alguna manera, protegir l’altre, és omplir aquest espai buit que existeix entre el meu món i un món del qual no sé moltes coses o les que sé massa sovint fan tuf d’estereotip. No hi ha dubte que aquest buit s’omple amb paraules, però també amb allò que anomenem simpatia, la capacitat de buscar l’espai on convergeixen experiències i sentiments. Aproximar-se a l’altre sense deixar-se dur pels prejudicis, amb la voluntat de trencar les possibles asimetries que puguin existir perquè l’altre no parla com jo, perquè no és d’aquí, perquè desconeix els nostres costums, etc. Crear vincles comporta allò que alguns autors anomenen descentrar-se, d’altres exposar-se a la diferència i uns altres reduir la distància social. S’ha de tenir la capacitat de sortir del propi jo i de la manera com els meus pensen i viuen el món per afegir-se i implicar-se en un espai col·lectiu. Crear vincles, perquè tothom necessita sentir-se respectat per la llei, valorat per la societat i estimat pel grup.

Contrastar per aprendre. El contrast, el fet de transitar entre cultures i llengües per aprendre, no l’associem ni a una superposició, ni a accions esporàdiques ni a cap tipus d’imposició, sinó a un estímul per al creixement personal. La diferència no és una anècdota. La diferència s’ha de reconèixer en la seva identitat i validesa. És en aquest punt on discrepen els discursos que parlen de tolerància i els que apunten cap al plurilingüisme. Tolerància és concessió i, per tant, la mirada és unidireccional; plurilingüisme és reconeixement, i en el reconeixement la mirada es mou sempre en dues direccions: el nen se sent mirat pel seu mestre, mentre que el mestre sent la mirada del nen, una mirada que reclama un procés de comprensió. En el marc d’una educació plurilingüe res ni ningú és estrany, perquè hi ha un constant transitar entre totes les maneres de sentir, de fer i de dir. Contrastar per aprendre, perquè quan el coneixement fa un viatge cap a llocs desconeguts, mai no retorna de la mateixa manera.

Informació extreta de: Palou Sangrà, J. i Fons Esteve, M. (coord.) (2019). La competencia plurilingüe a l’escola. Experiències i reflexions. Octaedro. https://octaedro.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/80184.pdf

Vivim en una societat cada vegada més multilingüe i multicultural, i l’escola ha de procurar reflectir aquesta diversitat. El repte de l’educació plurilingüe és enorme: formar persones plurilingües tot assegurant que la seua formació incloga la llengua minoritzada.

Podem dir que habitualment no es considera la diversitat de llengües i cultures que conviuen en l’àmbit escolar, sinó que més bé hi ha una separació dels continguts escolars en relació amb les àrees de llengua, la qual cosa propicia, per exemple, la repetició de conceptes i la variació de terminologia referida a un mateix terme segons les diferents tradicions gramaticals o els marcs de referència teòrics. La realitat plurilingüe planteja la necessitat d’abordar la reflexió metalingüística d’una manera relacionada, mitjançant la comparació dels diferents fenòmens a partir de les llengües que coneix l’alumnat. Des d’un plantejament integrat de les llengües del currículum resulta imprescindible el tractament unificat de la teoria lingüística amb l’objectiu de millorar les pràctiques educatives. Aquesta situació lingüística als centres educatius hauria de ser també l’ocasió de repensar les maneres d’ensenyar i d’aprendre, en general, i les llengües en particular.

Les fronteres lingüístiques sovint no coincideixen amb les fronteres territorials. De fet, el multilingüisme estatal és habitual; el que és estrany és trobar un estat on sols es parle una llengua. L’existència d’una sola comunitat lingüística dins d’un mateix estat és una situació excepcional, ja que el més usual és l’existència de diverses comunitats lingüístiques dins d’un mateix estat. Tot això ha fet que cada estat adopte polítiques lingüístiques diferents, orientades bé a promoure l’ús de la llengua oficial triada i eliminar-ne totes les altres, o bé a promoure l’ús de totes les llengües.

D’acord amb Nicolás (2021), en didàctica de llengües es recomana usar termes neutres, menys connotats que el de llengua materna, com llengua familiar o llengua primera (L1, first language), per contraposició a llengua segona o llengua adquirida (L2, second language). A més, en l’àmbit de l’ensenyament de llengües en un context plurilingüe i, en territoris amb dues llengües oficials, com assenyala Bataller (2019), s’imposa la diferenciació entre L1 i L2, que gaudeixen d’un estatus oficial, i LE, sense estatus oficial. En la nostra peculiar situació sociolingüística hi ha una notable diferència entre el que entenem per segones llengües. Mentre que unes són llengües realment estrangeres (anglés, francés, etc.), el català o el castellà, segons els casos, són llengües presents, en més o menys grau, en el context del nostre alumnat per més que només una siga la seua primera llengua i, d’aquestes dues, només n’hi ha una, el català, que siga la pròpia del país. En aquest sentit, convé afegir que, en lloc de fer servir el terme llengua estrangera (LE), emprem el terme llengua addicional (LA), entesa com aquella que s’aprén amb posterioritat a l’adquisició del llenguatge mitjançant la primera llengua.

La diversitat lingüística i cultural, tan característica del segle XXI, ha promogut l’avanç de l’interés per l’aprenentatge de la llengua en contextos multilingües. Boix i Vila (1998) anomenen monolingüista el model utilitzat per estats que trien una única varietat com a llengua nacional. Al seu costat pensen que existeixen altres dos models: el plurilingüista, que assumeix en graus diferents la diversitat lingüística dels ciutadans, i el model de control, que permet als grups subordinats un grau variable d’autonomia col·lectiva, amb una política lingüística delegada, però sempre dins dels límits fixats pel grup dominant, i havent d’adaptar-se als valors i les normes del grup majoritari.

El programa d’immersió lingüística és un model d’educació que s’inscriu en els anomenats models d’enriquiment (Fishman, 1976) i es correspon amb els programes de bilingüisme total. Etimològicament, la paraula immersió correspon a la imatge de la natació, de posar-se totalment envoltat de l’aigua, i en el nostre cas envoltar-se d’una manera natural, específica i amb unes certes condicions, de la llengua que es vol aprendre, que es vol fer seua. és l’adquisició d’una nova llengua en unes circumstàncies especials, que no s’oposen als principis de 1928 de l’Oficina de Luxemburg ni als principis de la UNESCO. La immersió lingüística no respon a la destrucció d’una llengua sinó més aviat a una major igualació i, d’una manera especial, a un fer-se seua –o donar les possibilitats per fer-se seua– una llengua fins aleshores estranya, totalment o en part.

Es tracta d’un programa d’ensenyament en l’L2, adreçat a l’alumnat de llengua i cultura majoritària, els objectius del qual són el bilingüisme i el biculturalisme. L’alumnat manté l’L1 pel tractament que té en l’escola i pel suport i l’estatus que té fora del context escolar i aprén l’L2 mitjançant un procés natural, no forçat, a través de l’ús d’aquesta en el treball de les matèries del currículum. Són programes considerats d’alt grau d’èxit, perquè el rendiment acadèmic és el mateix que el de l’alumnat que aprén en l’L1 i desenvolupen una major competència en l’L2. Promouen el bilingüisme additiu perquè afegeixen al coneixement de la pròpia llengua i cultura, el coneixement de l’altra.

Segons la Llei de plurilingüisme, els equips docents han d’adaptar les programacions d’aula als objectius previstos en el Projecte lingüístic de centre (PLC) i prendre com a referència metodològica l’aprenentatge integrat de llengües i continguts i enfocaments plurals o metodologies actives que prioritzen el paper de l’alumnat, que ha de ser el centre del procés educatiu, i potencien l’ús de la llengua.

Informació extreta de Martí Climent, A. (2022). Projecte docent. Desenvolupament d’habilitats comunicatives en contextos multilingües. UV.

MODELS I INTERVENCIÓ DIDÀCTICA

Com veiem en la proposta del Model d’educació plurilingüe i intercultural, el sistema educatiu s’estructura en tres nivells: el Marc institucional, que estableix els objectius, l’organització en un programa únic d’educació plurilingüe i intercultural, i el currículum oficial integrat; el Projecte educatiu de centre, per mitjà del qual els equips docents, dins l’espai que proporciona el Marc Institucional, organitzen l’ensenyament i ús vehicular de les llengües, la normalització de l’ús social i institucional del valencià, i la promoció del valencià en les relacions del centre amb les famílies i l’entorn; i la Intervenció didàctica a l’aula, en la qual es gestiona l’ús de les llengües a classe, i es planifiquen i s’apliquen les activitats d’ensenyament-aprenentatge.

Els resultats del sistema educatiu, doncs, no depenen solament de la Intervenció Didàctica, és a dir, del treball a classe dels professors i dels alumnes, sinó de la influència conjunta dels diversos nivells. Qualsevol intent d’avaluació del rendiment dels alumnes haurà de tenir-los tots en compte i analitzar la influència de cadascun en els resultats.

Figura 1: Estructura del Model d’educació plurilingüe i intercultural (Baldaquí i Pascual, 2021)

Més enllà de les previsions d’un programa d’educació plurilingüe, l’important és com s’aplica, és a dir, què s’esdevé realment a les classes. En realitat és el professorat a l’aula qui afronta els problemes més complexos: la necessitat d’impartir un mateix currículum a un conjunt divers d’alumnes, l’actitud més o menys negativa de les famílies i dels alumnes envers l’ensenyament i ús vehicular de la llengua minoritzada, el desconeixement de la llengua vehicular per una part dels alumnes, la inadequació dels materials curriculars per a un ensenyament plurilingüe, etc. I sempre des de la perspectiva de la inclusió, intentant que cada alumne arribe al màxim de les seues potencialitats independentment de la seua posició de partida. Fer possible, en aquestes circumstàncies, que aquest alumnat tan heterogeni assolisca els objectius del currículum i que prenga consciència dels avantatges i possibilitats que planteja el domini del valencià, que n’adquirisca una competència òptima i que referme la seua voluntat de comunicar-se habitualment en aquesta llengua tant si és la seua L1 com si no ho és implica prendre decisions en dos àmbits, en la gestió de les llengües a l’aula i en la planificació i actuació didàctica.

Per tal d’assolir els objectius de la Llei de Plurilingüisme, Baldaquí i Pascual (2021) proposen un model d’educació plurilingüe i intercultural autocentrat, un model de mínims per a avançar en la construcció de l’escola valenciana que hauria de:

a) convertir el valencià en nucli de la planificació lingüística i educativa;

b) adoptar una perspectiva pròpia, valenciana, sobre el currículum;

i c) promoure actituds favorables envers el valencià i el seu ús com a llengua habitual.

Informació extreta de Baldaquí, J. M. i Pasqual, V. (2021). Gestió de les llengües en entorns educatius multilingües: una perspectiva valenciana. Revista de Llengua i Dret, Journal of Language of Law, 75, 64-84. https://doi.org/10.2436/rld.i75.2021.3588

CAP A L’APRENENTATGE COMPETENCIAL DE LLENGÜES ADDICIONALS

En els plantejaments en didàctica de llengües addicionals en què es basa el Marc Comú Europeu de Referència, es defensa la necessitat de formular els objectius d’aprenentatge en termes de competències. Les competències especifiquen allò que els estudiants hauran de ser capaços de saber fer en finalitzar les diverses fases o etapes del procés d’aprenentatge.

D’acord amb aquest plantejament, els nous enfocaments metodològics centren el procés més en l’aprenent que no pas en la matèria d’aprenentatge, alhora que fan visible l’alumne com a protagonista i responsable del seu procés. Des d’aquesta perspectiva s’emfasitza la necessitat d’entendre l’ensenyament d’una llengua addicional com a capacitació, en lloc d’entendre-la únicament com a instrucció.

El foment de la competència plurilingüe esdevé cabdal, perquè es refereix a la capacitat –inherent a tots els parlants bilingües i plurilingües– d’interrelacionar les llengües: l’individu no emmagatzema aquestes llengües i cultures en els calaixos d’una calaixera, en compartiments mentals estancs, sinó que desenvolupa una competència comunicativa a la qual contribueixen tots els coneixements i totes les experiències lingüístiques. Les llengües s’interrelacionen i interactuen en la ment dels estudiants.

Informació extreta de: Esteve, O.; Vilà, M. (2018): Cap a l’aprenentatge competencial de llengües addicionals. Articles de Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura. 78. Graó.

Per poder interpretar tant els progressos com les dificultats dels alumnes que estan aprenent i proporcionar-los un ensenyament personalitzat, els docents haurien de tenir en compte les característiques del procés d’aprenentatge d’una llengua addicional en un context acadèmic:

-

Complex: presenta multiplicitat de processos intermedis, multiplicitat de rutes i causes.

-

Gradual: implica fer encaixar formes, significats i usos.

-

No lineal: quan es reestructuren els coneixements adquirits hi ha aparents recaigudes i moments d’aparent estancament.

-

Dinàmic: els factors i les estratègies d’aprenentatge canvien al llarg del procés.

-

No influenciable: els alumnes aprenen determinats continguts quan estan preparats per fer-ho, és a dir, en uns determinats estadis d’aprenentatge.

-

Irregular: no tothom aprèn al mateix ritme ni arriba a assolir el mateix nivell.

-

Social: les interaccions entre parlants de L1 i parlants de L2 o les que es produeixen entre parlants d’una L2 són clau per al desenvolupament del procés d’aprenentatge.

-

Mobilitzador de coneixements i experiències prèvies que ja posseeixen: els aprenents es formulen, de manera més o menys conscient, hipòtesis sobre com s’articula el que volen dir i ho comproven a partir de la interacció amb els altres parlants.

-

Obert a la millora a través de l’acció educativa adequada: els alumnes que reben un ensenyament formal de la llengua i que desenvolupen processos de reflexió i interacció controlats no fossilitzen formes errònies a la seva interllengua, sinó que poden evolucionar cap a un domini de la L2. En aquest punt, s’ha de remarcar que, segons la recerca, la correcció sistemàtica i immediata no sembla gaire productiva. S’ha d’evitar treballar la llengua seguint llistats i paradigmes morfològics i, en canvi, s’ha d’articular activitats significatives i contextualitzades en processos didàctics amplis i que tinguin sentit per als aprenents.

Aquestes característiques específiques de l’aprenentatge inicial d’una llengua no han de fer perdre de vista que, si bé calen suports específics, també és indispensable que els alumnes participin de les aules ordinàries des del primer moment i progressin tant en l’aprenentatge de llengües com en els continguts de totes les àrees i matèries.

Informació extreta d’ADCL – Didàctica del català com a segona llengua per a l’alumnat nouvingut. Gencat.cat

L’EDUCACIó éS UNA CONVERSA

En el món de l’educació assistim diàriament a una conversa entre la cultura de l’escola i la cultura de l’alumnat, entre el món adult i el món infantil, adolescent i jove. Per aquest motiu, i amb la finalitat que aquesta conversa no acabi sent un monòleg a càrrec de les mestres i dels mestres, convindrà que la cultura acadèmica (el currículum i especialment les activitats que es realitzin a l’aula) s’obri a l’anàlisi i a la reflexió sobre les cultures de referència dels nois i de les noies presents a les institucions pedagògiques, i en conseqüència en tingui en compte les llengües, els hàbits culturals i les maneres com utilitzen el llenguatge, amb la qual cosa l’educació esdevindrà un diàleg intercultural entre docents i estudiants, en què l’aprenentatge es construirà a partir del que ja saben, del que ja saben fer i del que són els qui acudeixen a les aules.

La pedagogia del llenguatge ha de saber conjugar l’estimació de la diversitat lingüística a les aules (llengües, registres, estils, sociolectes, dialectes geogràfics…) i la crítica als prejudicis culturals que s’observen sovint sobre algunes llengües, els seus parlants i els seus usos (i especialment sobre les llengües i els usos de l’alumnat originari d’entorns desfavorits i vulnerables), amb l’objectiu d’acostar les noies i els nois a unes altres maneres de dir, a uns altres gèneres orals i escrits, a uns altres registres del llenguatge, a uns altres entorns comunicatius i a unes altres cultures alienes als seus contextos quotidians, i assegurar així el dret de l’alumnat a saber fer altres coses amb les paraules en unes situacions diverses de comunicació.

COMPETèNCIA COMUNICATIVA I CAPITAL CULTURAL

L’educació lingüística ha de fomentar l’emancipació comunicativa de l’alumnat, és a dir, la seva competència comunicativa a l’hora d’utilitzar de manera apropiada les formes adequades del llenguatge en cada context i situació de comunicació (inclosos els contextos públics i les situacions formals d’interacció), sense menysprear-ne les formes originàries de dir, absolutament legítimes, coherents i eficaces als seus entorns informals i familiars. Solament en la mesura que les seves maneres d’utilitzar el llenguatge siguin objecte de valoració i d’estima a les aules, sense prejudicis ni menyspreus (i sense obsessió normativa), l’alumnat atorgarà sentit al que aprèn mitjançant el contrast entre els seus usos habituals de la llengua i les pràctiques socials del llenguatge que són obligades en altres contextos tan diferents de l’entorn familiar i cultural en què viuen. Al capdavall, la competència comunicativa de les persones no solament és l’objectiu essencial de l’educació lingüística. és també, i sobretot, un capital cultural d’innegable valor a les nostres societats.

Informació extreta de: Lomas, C.; Jurado, F. (2021): Llengua de l’alumnat, llengua de l’escola. Articles de Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura. 91. Graó.