Active methodologies. Successful projects: TIL, TILC, translanguage, work by areas, PBL, interdisciplinary projects, service-learning, cooperative learning, didactic sequences, gamification, geolocation, personalization of learning, etc.

“We either educate to avoid the hierarchical organization of languages or minoritarian languages are lost” (Juli Palou)

5.1. Active methodologies. Successful projects: ILT, ILCT, PBL, translanguage, working per fields, interdisciplinary projects, learning-service, cooperative learning, didactic sequences, gamification, geolocalization, etc.

We propose working with active methodologies that involve students and make them the main characters: Project-Based Learning (PBL), Cooperative Learning (CL), didactical sequences (DS) that are able to get through to students, Learn to Learn (LL) and Competence Learning (CL), with resources such as gamification or geolocalization.

One of the options that better allows for the integration of languages and contents is project-based learning with digital tools (ICT), which allow to promote creativity, ease the elaboration and dissemination of the final product.

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is a centenarian innovation, as Trujillo (2017) says. Its origins can be traced to the United States between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, specially to Kilpatrick’s 1918 proposal. This educational proposal has an enormous potential, especially in linguistic areas, since there is “a broader proportion of flexible curricular elements, social applications and related to the know-how” (Trujillo, 2017: 46).

The main objectives to be promoted with this technology are: attention to diversity in the students’ interests and skills, integrate the four linguistic skills, foster interdisciplinary relationships, and introduce educational assessment. We prioritize the importance of cooperative work and the individual learning effort, as well as the fact to start research activities, analysis, and internalization of information, and its relationship with the social context in with the learning takes place (according to Camps and Vilà, 1994).

The methodological approach is based in the development of a work project related to a curricular area with the use of ICT. They prepare organized and sequenced activities depending on a particular result or product (a linguistic route, an audiovisual project…). There are many advantages. For example: to integrate the work of various kinds of texts, to grant importance to reading, writing and orality activities, and to promote the assimilation of learning. As opposed to the traditional teaching model, the insertion of contents in a project, that follow an itinerary until we arrive to a final product, gives consistency and sense to learning.

Trujillo (2017) points out that PBL is an innovative, assessable and observable strategy. It furnishes, through the use of portfolios, headings and learning diaries, many data that allow us to know if the learning has been effective, if there have been difficulties, as well as assess in order to grade and to regulate learning.

In order to prepare projects, we design activities to follow a didactic sequence (DS) model that is open, and not an unmovable design, that includes a communicational approach and that integrates the interaction between teachers and students.

According to Camps (1996), a language project includes three phases: preparation, development, and assessment. In the first one, we present the goals and objectives of the project. In the second one, we organize the planning activities for contents, textualization and revision, both adapted to the students’ learning process. In the third phase, we assess the final project together with the process followed by the students during the project development phase. Each project will define what activities are more appropriate.

We must point out the importance of three defining traits that are considered key to develop in a didactically efficient manner the DS and that we adopt from Milian’s and Camps’ (2006) proposal: the activity, the development and the DS resulting project, the process to stimulate metalinguistic reasoning, and the interaction between teachers and students.

PLANIFICATION

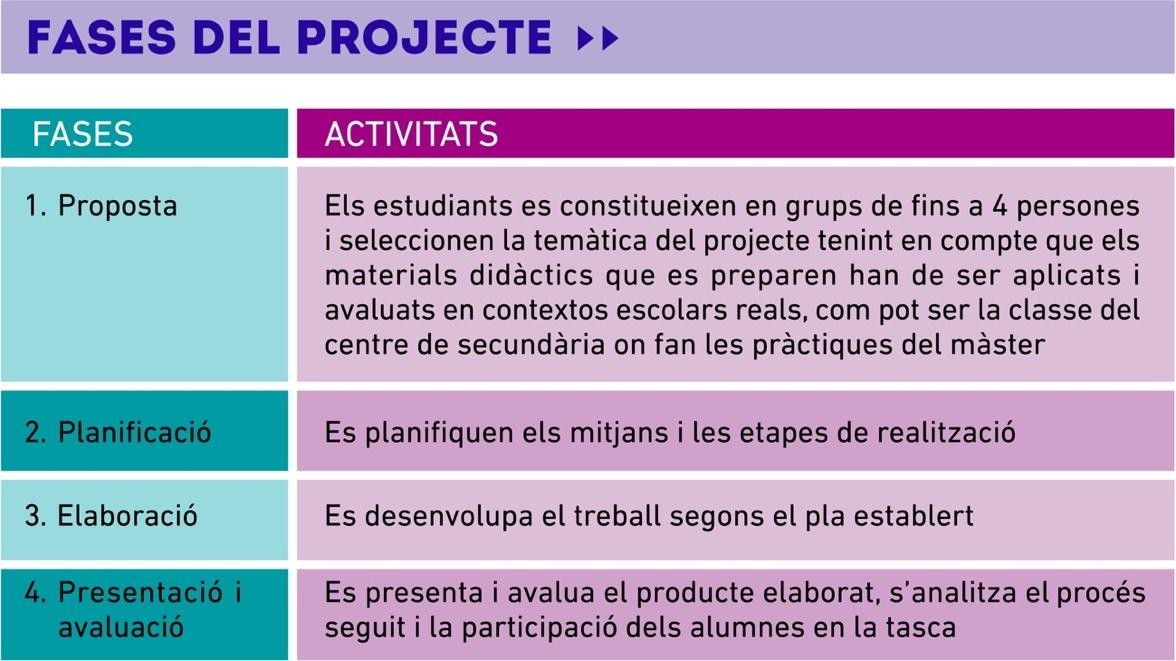

The activity sequence we present follows Kilpatrick’s 1918 proposal when he defined the project methodology as a working plan that intends to realize something that wakes up one’s own interest. The working phases are: approach or proposal, planification or development, and presentation and assessment.

Chart 1. Outline of the working project phases (proprietary production)

1st phase: Proposal. The working groups are created, in an heterogeneous manner, allowing the promotion of cooperative work. The projects are defined as per the proposed models with the ICT resources that will be used.

2nd phase: Planification. There is a follow-up of the project organization and groups are training on the use of ICTs and their didactical application.

Chart 2. Index card for a work project planification (proprietary production)

3rd phase: Development. Collection of information, activity development in DS and production of the final product.

4th phase. Presentation and assessment. The groups present their projects, and the rest of the class assesses their peers’ work, making notes of the interesting aspects and asking questions that they might have related with the presented themes. Afterwards, there is a discussion to talk about the difficulties and advantages found in the different projects. Furthermore, each students must individually answer an assessment questionnaire to evaluate the originality, structure and interest of the presented projects, as well as the presentation done by each group.

It is important to disseminate the project in social media (YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, etc.), or with presentations in the school or the city, or participating in contexts related with the project.

The results must have a communicational and didactic intent, as Barroso (2013) states, establishing a series of general principles where we need to clearly state that learning is not depending on the means, but on didactical strategies and techniques that we can apply. ICTs must be integrated in the curriculum to benefit from their enormous potential as means to promote communication processes, as well as for innovation and for an improvement of educational practices.

INFORMATIONAL COMPETENCES IN THE CLASSROOM

The term informational competences is born from the need to find a specific term to designate learning and teaching concepts, skills and attitudes related with the use of the information, while integrating the different languages and communicational means, and involving all processes related to the search, treatment and use of information that take place, in order to facilitate the transformation of information into knowledge. The term is recent, but the processes and skills that it implies have always existed, though linked only to written culture.

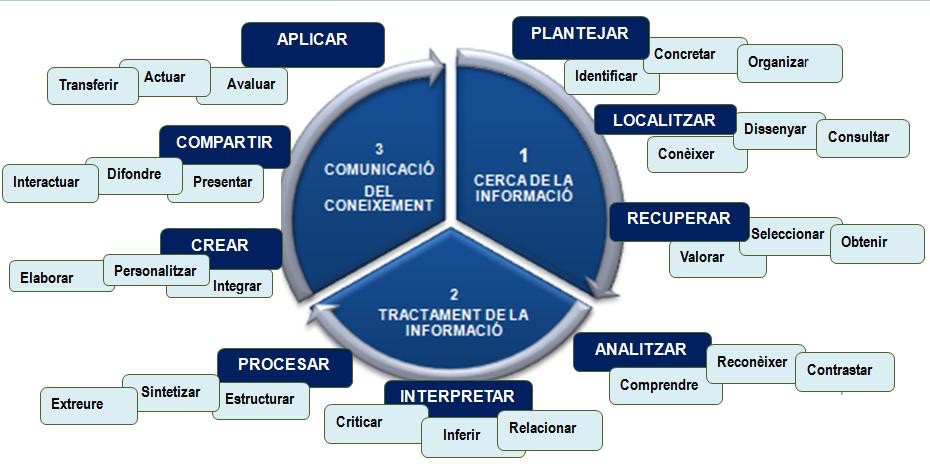

We must emphasize the cognitive and linguistic processes that activate the information management and the knowledge creation. The idea is to learn how to think, decide and share. It includes three main skills that are developed in the following image:

Chart 3. Outline representing the three informational competence capacities, which develop 3 skills and three 3 basic abilities

Chart 4. Summary on informational competence related to other competences

The idea is not to stop disseminating contents, but to learn how to think with, starting from and through contents.

RESEARCH PROCESS IN AN DS

1. Starting with an engine starting point. The idea is to present a situation-problem to be resolved and to trigger a key question.

2. Activating previous knowledge. Students must be able to express and communicate with others regarding what they think about the presented question.

3. Formulating a hypothesis. We must ease the formulation of ideas regarding the situation-problem and, consequently, activate the search for possible responses.

4. Planning the research. Allows the organization of a working plan and the definition of the time-line for the tasks to be performed.

5. Performing the planned activities. They are actions that will allow the students to reach out for information and refers to the specific process of information localization and recovery.

6. Interpreting the results and reaching the conclusions. These are indispensable actions to validate or refute the starting hypothesis and become key to generate personal knowledge.

7. Expressing and communicating the results of the research. The research process ends with the elaboration of a particular product that can be relevant, that has the aim of compiling and communicating the conclusions obtained after the information search.

8. Reflecting on the learning and the process. The real closure of the learning activity requires a metacognitive process that the teacher must necessarily drive.

Before guiding the students, the teachers must have defined the several aspects that define the reach of the information need. There are two main ones:

-

content quality of the search object (generical or specific)

-

the amount of information that we need (a little, a lot, in the middle). We define this by specifying a minimum or maximum of documents to be found.

Extracted from the web Informational competence in the classroom.

PROPOSALS FOR ITL (Integral Treatment of Languages)

The linguistic integral approach constitutes a basic principle in education to achieve/build a multilingual society (Apráiz et al., 2012; Ibarluzea et al., 2021), to elaborate a unique program for all languages with common objectives, methodologies and assessment criteria, and with distributed learning contents, but practically no language integration models have been developed (Dolz and Idiazabal, 2013).

Some authors suggest terms like translanguaging (García, 2009; Vallejo and Dooly, 2020) and multiliteracies (García and Kleifgen, 2020) to emphasize that communicational competences in multilingual speakers are dynamic and heterogeneous. Cenoz and Gorter (2017) defend a sustainable translanguaging in a context of use of regional minority languages, in the frame of pedagogical translanguaging (Cenoz and Gorter, 2019, 2020).

Diverse researches prove that the use of familiar languages (FL) in the classroom fosters a better integration of students with immigration backgrounds and a better assessment of the own identity (Cummins, 2001; Stille and Cummins, 2013), as well as a proper development of multilingual competence and an improvement of learning results (Ball, 2010, and Benson, 2009, quoted by Portolés, 2020).

The Council of Europe recommends lending value to and use linguistic diversity, including languages that are not taught in schools, as a learning resource, implying the families in language learning (Council of Europe, 2019). As a matter of fact, in the promotion of multilingual education in current European educational systems, as Portolés (2020) states, there is a dominant trend regarding the inclusion, maintenance and promotion of minoritarian and family languages. In this sense, Portolés (2020) defends an “educational system where all the students’ languages, regardless of whether they are inherited, local or global, are known, acknowledge and valued as learning means” (p. 139).

Torralba and Marzà (2022) proof that identarian texts are an ideal tool to work on the diverse linguistic repertoires that are present in multilingual classrooms and talk about the need of working in a planned manner with familiar languages during the whole schooling period, including integrating the families into the project. We define linguistic repertoire, following Palou (2011: 19), as a group of different languages or a series of linguistic varieties, learned in particular circumstances and that can be used in different situations.

Diverse researches proof that including familiar languages in the classroom improves the integration of students with immigrant backgrounds and increases the appraisal of their own identities (Cummins, 2001; Cummins and Stille, 2013). But benefits are not only identarian. In the United States, Thomas and Collier (2002) observe that the best predictor for the English level for non-English speaking students is the degree of formal schooling in their native language. Similarly, in our context, Oller and Vila (2011) state that foreign students in Catalan contexts that use their own language in a familiar context with an academical goal, that is, to read it and not only to talk, obtain good results in written Catalan and Castilian, while those that only use them for the daily familiar exchanges, but not academically, have worst results in these areas (Torralba, Marzà, 2022)

To be competent from a plurilingual point of view, it is essential to know languages and how to manage them. Intercultural and plurilingual competence is not a superposition or adding up of monolingual competences (Palou and Fons, 2019a, 2019b). These authors also state that there are three key concepts in this competence: receive, create links and contrast in order to learn. In this sense, Palou (2011) considers that teachers have two particular challenges:

“The first one: listen to the students’ voices. The second one: make sure that the experience aids in learning languages. To face these two challenges, it is necessary to create contexts that promote reflection on the linguistic repertoire. This metalinguistic and metacultural reflection will certainly help to gain awareness regarding the potential that linguistic diversity always has.“(Palou, 2011, p. 26)

In order to facilitate good learning conditions, Dolz et al. (2009) consider that language didactics for languages need means (didactical sequences) and a different set of tools to allow the teaching-learning of ideas and capacities applied to particular contents.

Information extracted from Martí Climent, A. (2022). Projecte docent. Desenvolupament d’habilitats comunicatives en contextos multilingües. UV.

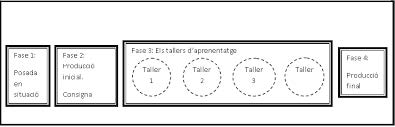

Chart 5: Diagram on didactic sequence (Dolz and Schneuwly, 2006)

More information under Dolz, J. and Schneuwly, B. (2006). Per un ensenyament de l’oral. Iniciació als gèneres formals a l’escola. València/Barcelona: Institut Interuniversitari de Filologia Valenciana i Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

PROPOSES FOR LCIT (Language and Content Integral Treatment)

LCIT is defined by “content treatment in one or more non-linguistic subjects —Science, History, Math, Arts…— together with the linguistic resources that are appropriate to learn one or more languages” (Pascual, 2008).

These treatment implies an interdisciplinary curricular organization type, that can include two or three subjects, coordination (possible connections between curriculum and methodology), flexibility (they can start with one issue to be faced from different perspectives in order to complete it or enrichen it), and co-teaching (more than one teacher per classroom).

We must, therefore, consider linguistic transfer and the linguistic peculiarities of each language when creating the programs. We must also work with diverse textual genres.

There are two parallel objectives: teaching the academic content of each of the different subjects, and simultaneously furnish competences in the language or languages upon which these contents are constructed.

When learning-teaching Valencian and Castilian as an L1, at least part of the contents of the communicational competence, what we call academic language, is processed better when it is integrated with non-linguistic areas (NLA) rather than when they are treated in the areas of the different languages themselves.

In LCIT we must focus on interdisciplinary and globalized approaches that promote collaborative construction of knowledge through document search, direct research, reflection, and production.

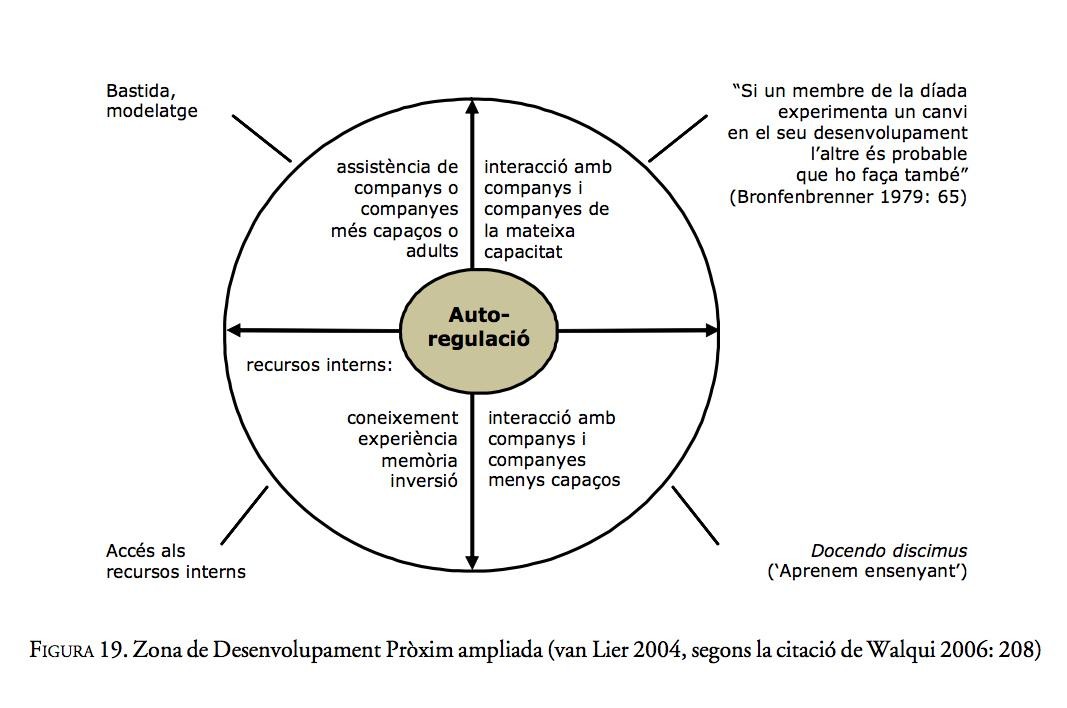

These approaches allow us to group students together in big groups, in working teams, in work in pairs or individual work. Furthermore, each of these grouping types must be strategically organized in order to guarantee the necessary support to complete the task, promote the collaborative work between students, and grant access to internal individual resources.

In this scaffolded learning, there is a redistribution of responsibility in the achievement of the task, that progressively goes from the teacher to the student. This participation is particularly visible when they work in projects with materials and resources:

-

Different formats in multimedia modalities.

-

From dissimilar sources with diverse perspectives, complementary visions and contrasting points of view. Appropriate for the comprehension skills of the students (it might be necessary to adapt).

-

External sources or sources created by the students themselves.

The didactic approach entails an experimental work; knowledge built upon different perspectives; deep command of languages for observation, analysis, experimentation, deductive reasoning, and the construction and communication of knowledge.

It is also key to use ITC as an additional working tool, considering the environment as the ideal study field to understand it, and the basic setting on which to act to improve it.

KEY COMPONENTS OF LCIT TO CREATE A DIDACTIC UNIT

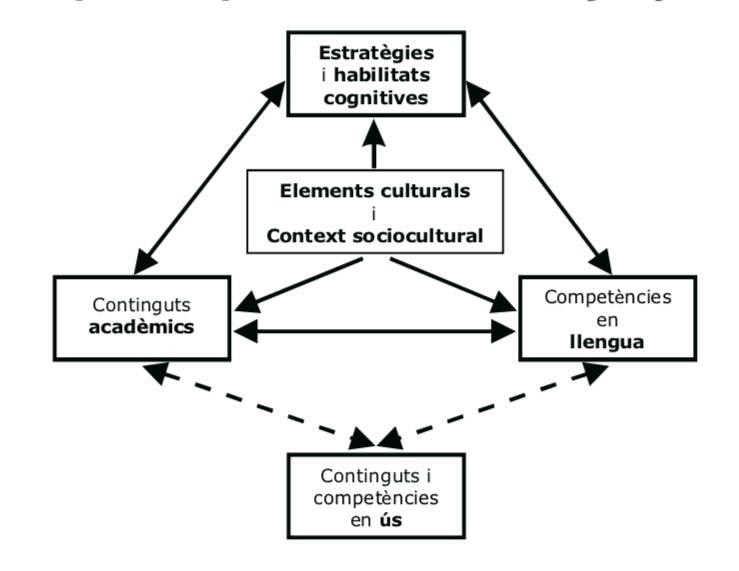

In the model presented by Pascual (2008) the key elements are: academic (contents in non-linguist areas), cognitive, and linguistic development; attention to use, and cultural elements and sociocultural context. Furthermore, these components are complex and are completely intertwined.

Figure 2: Model for the application of LCIT (Pascual, 2008)

STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION OF AN LCIT UNIT

A. Objectives, contents, and assessment criteria

|

Objectives |

Academic, linguistic, cognitive and cultural (independent or integrated) |

|

Contents |

Academic (facts and concepts, procedures and attitudes of non-linguistic areas). Linguistic:

Cognitive:

Cultural |

|

Assessment criteria |

Academic, linguistic, cognitive, and cultural (independent or integrated) |

B. Teaching/learning process

|

Before |

|

|

During |

Actitivies that allow students to:

|

|

After |

Actitivies that allow students to:

|

C. Curricular materials and resources

|

With different formats in different multi-reading-writing. From diverse sources and multiple perspectives, complementary views From diverse sources with diverse perspectives, complementary visions and contrasting points of view. Appropriate for the comprehension skills of the students (it might be necessary to adapt). External sources or sources created by the students themselves. |

D. Groupings

|

Flexible groupings, that allow:

|

E. Participation of the families and the social environment

|

They participate… |

As informants, from their home. As connoisseurs of the group culture, participating in the classroom. As experts on a subject, participating in the classroom. |

F. Assessment

|

Characteristics |

Must consider all the factors: contents, cognition, culture. Must be contextualized as teaching-learning. Must be contrasted with the parents’ opinion. |

|

Types |

Initial: explicitation of previous competences and knowledge. Continuous: control of the teaching/learning throughout the unit. Final: of the knowledge and the process (materials, teachers’ intervention, and teaching-learning process). |

Chart 5. Model of a unit, according to V. Pascual (2008), Caplletra 45

The linguistic content added to a unit must be:

- Integrated in the activities on subject content.

- Developed through class interaction.

Knowledge will be decontextualized and empty of meaning if it is limited to the classroom. In order to allow them to acquire their full educational and transformative potential, they must be generated/applied in a dialectal relationship with the environment, considering the learners’ perception regarding the unknown and the problems of their inner worlds, as well as the local or global reality that surrounds them. This perception allows them to ask questions and give answers, analyze problems, and furnish solutions. With these answers and these solutions they express their own vision of the world and their own identity. Additionally to explaining with scientific arguments the physical, natural, and social reality they live in, it allows students to critically analyse and do their part in changing it and improving it.

This new, researched, processed and critically-developed knowledge that has been acquired with a social action will, can easily be the final activity or product of a unit, and be shaped as:

|

Oral documents |

Oral presentation, debate, theater play… |

|

Written documents |

Written report, mural, album, report, feature, leaflet, manual, poster… |

Chart 6. Final activities to synthesize/generate new knowledge

In LCIT, therefore, we find a transformative and critical pedagogy that allows for the generation of new knowledge and for action upon the social reality, avoiding the use of didactical approaches aimed towards one-way transmission of fragmented knowledge that has already been elaborated by the different academic disciplines and that must favor interdisciplinary and globalized approaches that promote the collaborative construction of knowledge through documental search, direct research, reflection, and production.

Information extracted from Pascual Granell, V. (2008). Components and organització d’una unitat amb un tractament integrat de llengua and continguts en una L2. En: Caplletra: Revista Internacional de Filologia, No. 45: 121

PROPOSALS FOR LIT/LCIT PROJECTS

The proposal “Home Languages, School Languages” was generated by a collaborative team of university researchers and schoolteachers. It is a didactic project revolting around culture and linguistic identity as a framework to provoke interactions in the classroom implying all familiar languages (García and Sylvan, 2011). The experience of adding familiar languages has been organized around what we call bilingual “identarian texts,” defined as creative products that the students generate in a pedagogical context, in written, spoken, visual, musical or dramatic forma, in this case, in the language or languages spoken at home, and the schooling language (Cummins and Early, 2011; Cummins et al, 2005).

The study “Home Languages, School Languages,” directed by, G. and Marzà, A. (2017), shows how the inclusion of familiar languages in the classroom fosters an improvement in the integration of immigrant students and an increase of their assessment of their own identities.

The research has taken place with the collaboration of three schools in the Castellón province, and, in it, the students have created so-called bilingual “identarian texts”, that is, texts that are written or uttered in the native language and the schooling language, where they reflect on their own identity. In this case, the children, often with the help of their families, have approached issues ranging from trips to gastronomy or politics, and have done so in Valencian and in the languages they talk at home, including Arabic, Chinese or Romanian.

On one hand, the results prove that it is possible to integrate in the classroom languages that are unknown to most of the students and the teachers. On the other hand, that thit sort of projects help develop integration and self-esteem of immigrant students, as well as the intercultural perspective of those of Spanish origin. Nevertheless, in the environment it is possible to observe that teachers are lacking more training in language integration to help them overcome their fears and the difficulties of working in a classroom with languages they do not know, hence the importance of this kind of projects.

You can see part of the project in this video: «Home Languages, School Languages»:

Information extracted from Torralba, G. and Marzà, A. (2017). «Home Languages, School Languages», de Gloria Torralba and Anna Marzà. Presented in the VIII International Seminar “L’aula com a àmbit d’investigació sobre l’ensenyament and l’aprenentatge de la llengua”. UVic-UCC. https://mon.uvic.cat/aula-investigacio-llengua/files/2015/12/TorralbaMarza.pdf

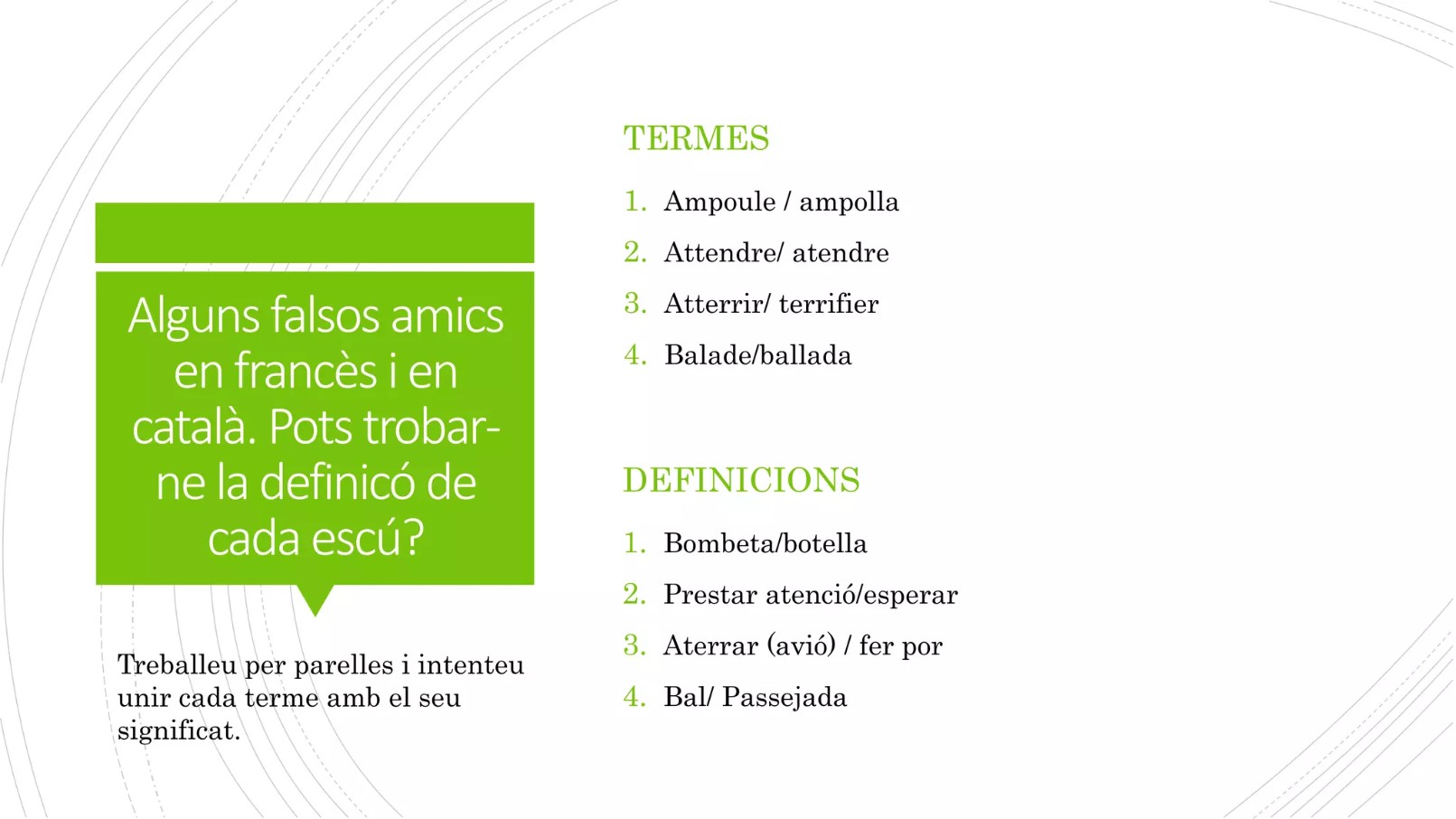

The EUROMANIA project is born from a European project aimed to reveal plurilingual interests and move towards plurilingual reading competences in seven Romance languages: Catalan, Castilian, French, Occitan, Romanian, Italian, and Portuguese.

The materials to work on the Euromania project is the result of three years of work in a group of experts. It has 20 files for multilingual learning in the following areas: Math, History, Science, and Technology. It is aimed at students with ages ranging from 8 to 12 years old.

The originality of the Euromania method lies in its duality. They work on the subjects with the aid of supports written in the Romance languages. At the same time, intercomprehension competences are built with the different areas’ support.

The document that exposes how to model a Euromania module, specifically unit 20 “Não te percas” by J. Ortiz (UPF) can be used as an example for the remaining modules, and allows for the observation of the linguistic elements to be considered when preparing classes. They also include supplementary materials.

- Module 1 : Le mystère du “mormoloc”

- Basic elements for the pronunciation of Romance languages

- Strategies to work on comprehension

Other materials and resources

Lecturio+ Project

Corpus of stories to develop intercomprehension in the classroom.

One-minute videos of scientific subjects in Catalan, French, and English. They include the text transcription.

Euromania handbook, Catalan version

Material to work on the Euromania Project written by an expert group. It has 20 files for multilingual learning in the following areas: Math, History, Science, and Technology. It is aimed at students with ages ranging from 8 to 12 years old.

Website to present a new project on minoritarian Romance languages. We can find information on their geographical location, their dialects, their current situation, a summarized grammar for each language, literary texts, etc.

Born from the will to integrate the study of all Romance languages in high school classrooms, and centered on reading comprehension.

Learning course to learn four Romance languages simultaneously (to choose between French, Italian, Catalan, Spanish, and Portuguese). The idea is to do it in a really short period of time, between thirty and forty hours, developing reading strategies that allow us to the linguistic commonalities between Romance languages.

Access to automatic translation tools between different languages:

Ethimology of words in European languages

Web including the ethimology of words in European languages.

DIDACTICAL PROJECTS

These projects have been designed with digital tools to develop curricular aspects of subjects like Language and Literature, and the Linguistic and Social fields in high school. Here are six proposals for projects, three for Language and three for Literature, to be developed in the classroom.

-

Linguistic route with several types. Creation of an itinerary to take a linguistic walk along the territories, town, city, neighborhood streets or mountains of the chosen geographic area. Students must discover the meaning of the name of the places that surround them. The final project is an audiovisual production or a graphic feature based on the programmed route to reflect the linguistic references of the visited places.

-

Video-ling. Dramatized audiovisual practices regarding linguistic questions. The students are divided into groups to prepare an instructive and explanatory text to learn how to correctly use a particular grammar or lexical issue. Furthermore, they must prepare a script for a dramatized text where there are examples of the correct and incorrect use of the issue in particular.

-

Typo-hunt.The students are divided into groups (4 or 5 per group). They must look for linguistic mistakes in their surroundings. After analyzing them, they must prepare an oral presentation with 20 slides with 20 seconds to present each one of them.

-

Literary enigmas. Game to discover the mysteries surrounding Valencian legends. The students are divided into groups that must overcome a challenge by solving a series of enigmas or related tests before the allocated time is over. It is an exceptional experience, since the students must read, discuss, have opinions, and contribute in order to achieve the goal of solving the enigma.

-

Video-review. The students are divided into groups and must film a video where they analyze artistic-literary books. The audiovisual product, with a maximum length of 5 minutes, must contain a valuative description of the work (plot, etc.), and also talk about the most relevant artistic aspects (images, comparison with traditional or original version, etc.), among others.

-

Video-story, video-poem. Audiovisual production based on the adaptation or creation of a narrative or poetic literary text. The students are divided into groups to film a video based on one of the programmed readings of the school year. It is possible to work with different genres and the end result can be a video-poem, when the result rhymes or a poetical image is created; or a video-story, if it is a narrative text.

More information: Martí Climent, Alícia; Garcia Vidal, Pilar (2020). DidàcTICs. Projectes de llengua i literatura per a l’aula de Secundària. Bromera.

PROGRAMMING BY SPHERES. PLANNING AND INTEGRATION OF LANGUAGES AND CONTENTS

The introduction of spheres in high school has brought a meaningful change to the school organization and their didactic planning. Factors such as co-teaching and didactic coordination, the integration of languages and contents, and the use of active methodologies allow for a more integrative and integral teaching. This fosters learning in the students, in a moment that is particularly sensitive: the change from primary to secondary school.

The integration of subjects promotes interdisciplinarity, and the integral treatment of languages (more important for regions with a co-official language) and the language and content treatment (LCIT). This project promotes the use of digital tools (ICT) and virtual learning environments (VLE).

On the other hand, we must underline that spheres are highly inclusive. The presence of two teachers allows for a better management of the conflicts inside the classroom, and also a better attention to educational needs and the different learning rhythms. This factor is further fostered with cooperative work, which promotes discussions within a respectful framework, an enrichening transference thanks to multiple intelligences, and the broadening of contents.

A key issue in this change in the professional culture is the learning between teachers thanks to co-teaching and to the weekly coordination meetings, that are translated into an extremely rewarding exchange of materials, strategies and techniques. Hence, we, as teachers, also learn from our peers, our students, and the possibilities of this new organizational framework we call “sphere.”

In the organization in spheres, any curricular area can be integrated in a linguistic area. Language teachers and those of the subject they are merged with prepare the program to make sure that the teaching-learning process makes sense and they use digital tools to promote this. Working with webs, with shared documents or in social media eases the collaboration, allows to review the activity sequence during the working process, and promotes the dissemination of the final product (Garcia Vidal, 2020).

In the spheres in the IES Serpis they agreed to create a newspaper, Mèdia Serpis: La veu dels àmbits, where they disseminate plurilingual projects developed during the school year, not only in the linguistic sphere, but also in the social and scientific spheres. Mèdia Serpis includes the section Serpis TV, environment, reading, science, culture and curiosities. The linguistic subjects can work on the journalistic genres.

Image 1: Project design Mèdia Serpis

The continuity of the sessions and the work programmed allows to develop didactical sequences with more time, favors interaction between teachers and students, the attention to diversity, inclusion, and training assessment.

Image 2: Website of the project Mèdia Serpis

Information extracted from Garcia Vidal, P.; Villar Porta, M. (2022). Programar per àmbits. Planificació i integració de llengües i continguts en l’àmbit sociolingüístic. Articles de Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura, 94, p. 35-40. Graó

More information on this working experience in the video GAUDIM ELS ÀMBITS 2020-21 and the presentation Els àmbits a l’IES Serpis: coordinació, metodologies and projectes

PROJECTS IN SPHERES

PROJECT: growing an ecological vegetable patch

We plant a vegetable patch in our school. The work will be assessed in the linguistic and social sphere, as well as the scientific one. Activities:

-Study vocabulary on tools and tasks in agriculture.

-Organizing and planning farming an ecological vegetable patch in coordination with the scientific sphere.

-Work to defend the environment and sustainability in the school.

-Listen to experts who advise us how to manage the vegetable patch.

Ecologic agriculture helps us obtain organic vegetables that are healthier while respecting and ensuring the ecological quality of the surroundings, and contributing to a better knowledge and respect of all the natural cycles for all the elements that are a part of this ecosystem.

Having a vegetable patch allows us to actively put in practice many of the foundations of sustainable culture, and is fun. However, it also requires us to be responsible and is challenging, since, in order to achieve results and progress, we need to take care of it and pay attention.

Apart from the produce, the following things are generated:

Class vegetable patch newspaper: We publish a newspaper every week.

Individual vegetable patchwork notebook: Every time you go to the vegetable patch with your team, you must explain what you did and included photographs or pictures.

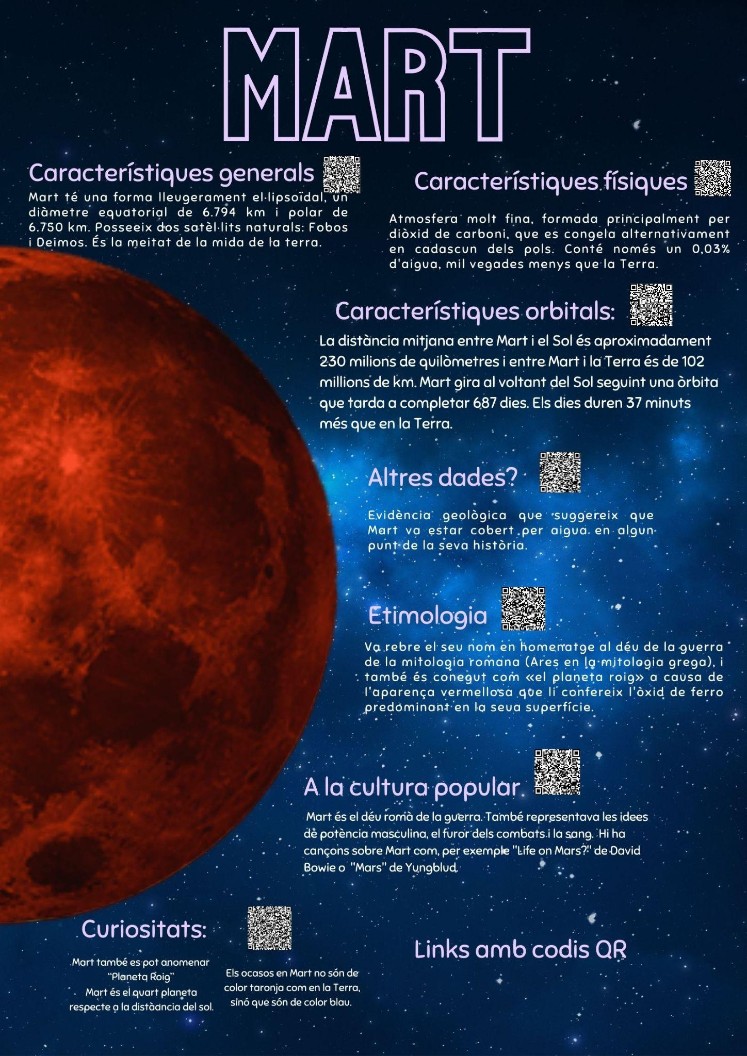

THE UNIVERSE: Projection on the planets in the Solar System

T

The science sphere is present in the design of the eight planets with cork semi-spheres that are hung from the ceiling of a long corridor in the high school. The distance between them is scaled. The students have decorated each semi-sphere using real images of the planets found on the web site:www.nasa.gov.

The sociolinguistic sphere is present in the preparation of informative panels that are hung next to the planets where there is information on their main characteristics and curious data on each one of them.

The project gives a global image of the work performed in the scientific and sociolinguistic spheres, by treating the same content from different and complementary perspectives.

SERVICE LEARNING (SL)

The SL is an educational proposal that combines learning processes with community service in a sole project that is very well articulated. The participants are trained while working on the real necessities of their surroundings with the intention of improving it.

More information in the web APRENENTATGE SERVEI

You can find more resources and experiences in SL in Gencat

TRANSLANGUAGE (TL)

This term defines the way in which people use the linguistic resources they have in the different languages they know. Researchers define it as “An approach regarding the use of language, bilingualism and education bilingual people that considers linguistic practices in bilinguals, not as two autonomous linguistic systems, as it was done traditionally, but a sole linguistic repertoire with traits that have been constructed socially as pertaining to two different languages” García & Wei (2014, p. 2).

The idea of combining different languages is associated to the integral language (and content) treatment that several schools and high schools already apply, where teachers are coordinated to avoid repeating content and so they can work on them in an integrated manner from the areas of Catalan, Castilian and the foreign language.

The critiques of translanguage can be faced with the following alternatives:

First, defend the use of scaffolding by teachers as a key strategy to motivate both language comprehension and production in students from multilingual environments (Lyster, 2019; Llompart et al., 2020). That includes, for example, helping students to use their L2 correctly during an activity.

Second, implementing approaches that combine different languages, so that they strengthen each other, and taking abilities and production needs into consideration, as well as having children understand two or more languages. That is, if a child has a high comprehension level in one language, they must be helped to produce in another language or vice-versa (rebalancing approach, Lyster 2007; 2016; 2019).

Third, in contexts where there are minority languages, like Catalan, it is necessary to implement a sustainable translanguage. For example, regarding the use of Basque, Cenoz and Gorter (2017) propose four principles to arrive to a sustainable TL for the cohabitation of minority language: 1) design safe spaces for the use of the minority language, 2) develop the need to use the minority language also in TL, 3) reinforce the metalinguistic reflection of all the languages in the linguistic repertoire, and 4) relate the spontaneous TL with pedagogical activities. From the principles described by the authors, the role granted to metalinguistic reflection in more than one language (or linguistic resources) so that students can reflect deeply on form and meaning is key. This principle is not new at all. It connects with the didactic tradition centered around the importance of metalinguistic reflection (Camps et al., 2005).

Translanguage makes us reflect on linguistic repertoires that the students have but let us not forget that sociolinguistic contexts are different when there is a cohabitation of languages with unequal power relationship.

Information extracted from Comajoan-Colomé, Ll. Tra, tra, translanguaging. Vilaweb. GELA.

Translanguage is using all of the linguistic repertoire “without considering the socially and politically limits defined for languages with a name.”

We often assume that bilinguals have a dominant language and that, therefore, there is a hierarchical relationship between the languages they speak.

A translanguage classroom takes the students’ whole linguistic system into consideration. It gives the change to deploy all their linguistic repertoire.

Students can speak and talk either language. The idea is to benefit from this potential. In school, we often forget the students’ linguistic repertoire. When we mention multilingualism, we talk about people with an L1 and then L2, L3, that are inferior. There is a hierarchy of languages.

When we mention plurilingualism, we mean the contact with different languages, but there is a different power depending on the languages, even though it is not present among speakers. In translanguage there is no hierarchy. The speakers merely select their linguistic repertoire. There is always an internal current between the languages we know. Translanguage is the space that is created when we deploy all of our linguistic repertoire, and we consider each person’s unitary linguistic system. When we do not consider translanguage, we are being unfair to students from linguistic minorities, and we assess learners with less than half of their repertoire.

It is important to consider what transformations are produced thanks to translanguage. Identities are complex, dynamic, and changing. Translanguage lives in border areas with linguistic minorities because it corrects the differences in power and the control systems that are integrated in the language conceptions due to colonial expansion. It is not a mere border crossing, but inhabiting a world, and it goes well beyond language.

Information extracted from the videos from García, Ofelia –What is translanguaging? and “Translanguaging” during the Multilingualism & Diversity Lectures (2017).

More information: web Multilingualism & Diversity Lectures (MuDiLe) 2017

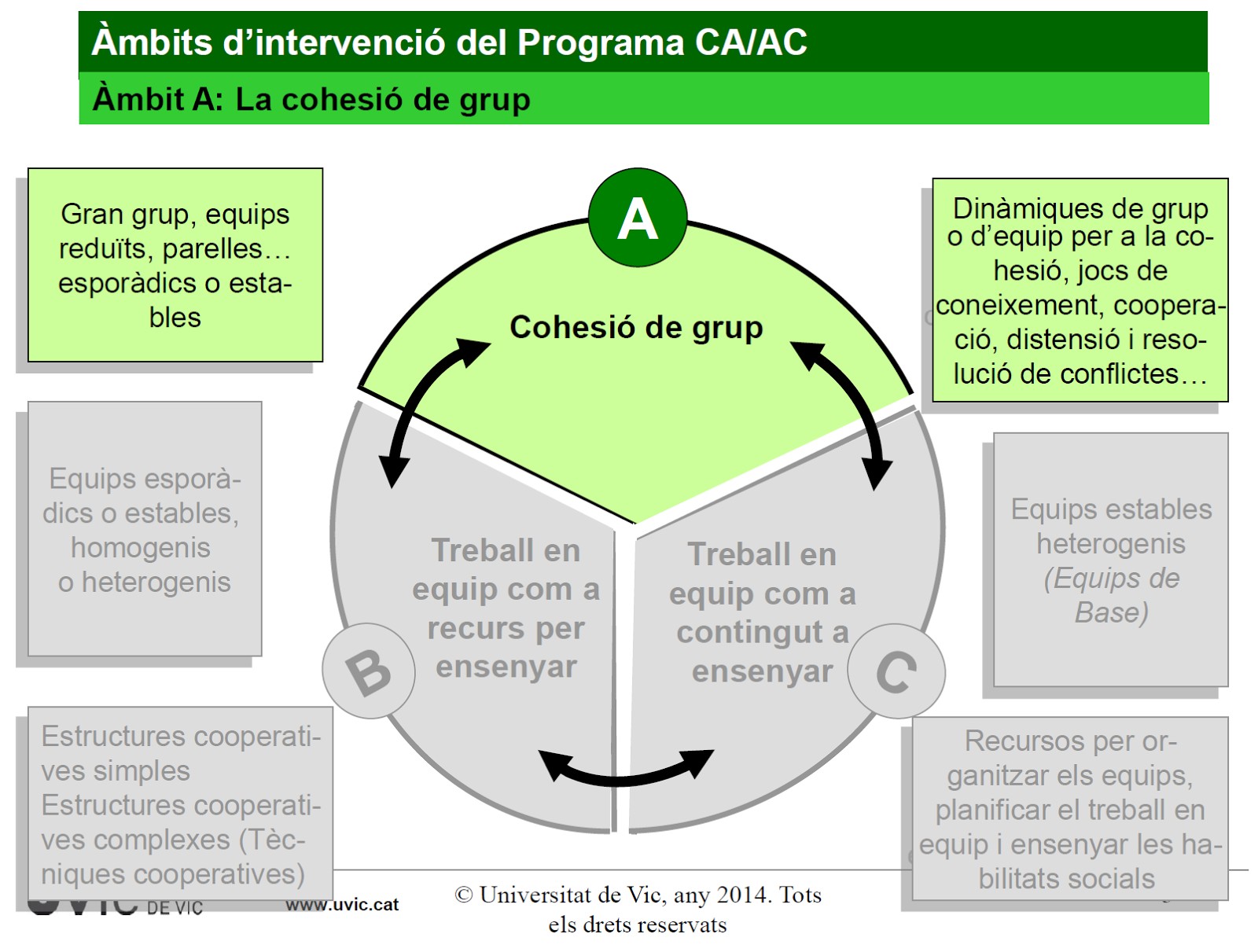

COOPERATIVE LEARNING

A key element in the methodology used in the teaching-learning process is the way to organize the educational activity in the classroom, which can be individual, competitive, or cooperative. As countless studies prove, cooperative organization in learning is a lot better, in many aspects, than individualistic and competitive organizations.

Image 3: Intervention spheres to implement cooperative learning in the classroom

Some cooperative structures

Three-minute stop

When the teacher explains to the whole class, they do a “three-minute stop” every now and then, so that each base team thinks and reflects on what has been explained to them up until then and they must think of three questions on the subject. When the three minutes are over, each team asks one of three questions they thought, one per team for each round. If that question or a similar one, has already been asked by another team, they skip it. When all the questions have been asked, the teacher continues with the explanation, until there is a new three-minute stop.

1-2-4

Within the base team, first (1) each one thinks what the right answer is of a question that has been asked by the teacher. Second, they come together in pairs (2), exchange responses and discuss them. Finally, and third, the whole team (4) has decided what the more appropriate answer to the answer is.

Spinning paper

The teachers gives a task to the base teams (a word list, writing a story, the things they know about a particular subject to know what their initial ideas are, a sentence that summarizes the key ideas of a text they read or the theme they have been studying, etc.), and a member of the team starts writing in a “spinning” paper. He or she passes it onto the person sitting next to them, and so on, until all the members of the team have participated. Each students can write their part with a different colored pen (the same one they used to write their name on the top of the paper), so that it is immediately clear who wrote what.

Pencil in the middle

In the structure “Pencil in the middle” the teacher gives each team a paper with as many questions or exercises on the subject they are studying in class as base team members (normally four). Each student is in charge of a question or exercise (they must read it out loud, making sure that all their peers contribute and express their opinion, and verify that they all know and understand the agreed answer). They decide the order of the exercises. When a student reads “their” question or exercise out loud and they all discuss how to do it and decide what the right answer is, everybody’s pencil is set on the center of the table to clarify that in that moment they can only talk and listen, but not write. When they all know what to do or how to solve the exercise, they each grab their own pencil and write the answer in their notebook. In that moment, no one can talk, just write. After, all pencils are placed again on the center of the table, and they proceed the same way with the next question or exercise, but this time directed by another student. And so on until all the exercises are finished.

The number

In “The number” the teacher gives the whole class a task (answer some questions, solve some problems, etc.). The students must finish the task with their base team, making sure that all the members know how to do it correctly. Each student has a number (for example, one assigned by alphabetical order). Once the time devoted to completing the task is finished, the teacher extracts a number from a bag where all the students’ numbers are. The chosen student must explain in front of all the class the task they have done or, if it is the case, solve it on the blackboard. If it is correct, he – and his team – obtain recognition, with public congratulations from the teacher and the rest of the teams.

Word game

The teacher writes on the blackboard some words related to the subject they are working on or have been working on. In each base team, each student must formulate a sentence with one of these words, or express the idea that is “behind” one of the words. Once they have written it down, they show their teammates, that can correct it, expand it, modify it, etc. until they consider it “theirs and the team’s.”

The key words can be the same for every team, or each base team can have their own key word list. The sentences or ideas generated with the key words of each team, when put together, are a summary of the whole theme.

Substance

It is an appropriate structure to determine key ideas – that are substantial – to a text or a theme. The teacher invites each student of a base team to write a sentence on the key idea of a text or of the theme they have been working on. Once they have written it, he shows it to the team mates and they all discuss if it is correct and, if it is not, correct it or nuance it. If it is not correct or they consider it does not apply to any of the key ideas, they set it apart. They do that with all of the sentences written by the team members. They do as many rounds as necessary until all the ideas they consider relevant or substantial have been expressed.

Once they have all the sentences they consider correct, they organize them in a logical manner and they then copy them to their notebooks. Like this, they have a summary of the text’s or theme’s key ideas. Anyway, when they copy onto their notebook, they do not have to merely copy literally, if they do not want to, the previously written sentences. They can insert changes or the sentences they find more appropriate.

Brain teaser

• We divide the class into heterogeneous teams with 4 or 5 members each.

• The content is divided into as many parts as members in the team, so that each member only receives a fragment of the information related to the issue that, when put together, is being studied by all the teams, and does not receive the ones available to the rest of their peers to prepare their own “subtheme.”

• Each team member prepares their part with the information furnished by the teacher or what they have found out themselves.

• After, with the members of the other teams that have studied the same subtheme, they create a “group of experts”, where the exchange information, delve into key concepts, create diagrams or conceptual maps, clarify doubts, etc.

• Then, everyone returns to their original team and is responsible to explain the part they prepared to the whole group.

Research Groups (RG)

-

Election and distribution of subthemes: students chose, depending on their skills or interests, specific subthemes within a general theme or problem, normally presented by the teacher following the curriculum.

-

Constitution of class teams: The teams must be as heterogeneous as possible. The ideal number of members ranges between 3 and 5.

-

Planning the study of the subtheme: Students in each team and the teacher plan their specific goals that they want to achieve and the procedures to acquire them. They also distribute the tasks (information search, organizing it, summarizing it, schematizing it, etc.)

-

Development of the plan: The students’ development in the designed plan. The teacher follow each teams’ progress and offer their help.

-

Analysis and synthesis: Students analyze and assess the information they have obtained. They summarize it in order to present it in front of the rest of the class.

-

Presenting the work: Once their subtheme has been exposed in front of the whole class, they ask questions and answer possible issues, doubts or extensions that can arise.

-

Assessment: The teacher and the students evaluate the team work and exhibition. It can be completed with an individual assessment.

It is not easy to work in cooperative learning teams. Individual structures are deeply rooted and, in the best-case scenario, even when our students do something in a team, they often end up presenting a series of small individual essays. Therefore, developing a series of actions to improve the environment in the classroom, and persuading people to work in teams is a first step that is necessary, but not enough. The use of cooperative structures and techniques can help us to render it possible, though we must be vigilant that they are not mere pseudo-cooperative structures. We must make sure that, within each team, everyone has a relevant role (responsibility and individual activity), and, at the same time, that there is more interaction between them. At any rate, which does not suffice. It is also necessary that students improve their team-working skills, so we must review the way the team works, and proposing improvement objectives is a good way to help them work better in a team.

Combining actions in these three fields is the best way to benefit from the advantages of working in cooperative teams as a learning tools. These advantages go beyond acquiring new knowledge in the different curricular areas and also furnish a wide range of social skills that are increasingly necessary in our current society.

Information extracted from Pujolàs Maset, P. (2008). Cooperar per aprendre and aprendre a cooperar: el treball en equips cooperatius com a recurs and com a contingut. Suports: revista catalana d’educació especial and atenció a la diversitat, 2008, Vol. 12, Núm. 1, p. 21-37,

https://raco.cat/index.php/Suports/article/view/120854

More information: PUJOLÀS, P.; LAGO, J.R. (2018). Aprender en equipos de aprendizaje cooperativo: El programa CA/AC (cooperar para aprender / aprender a cooperar). Octaedro.

“O eduquem per a evitar la jerarquització de les llengües o les llengües minoritàries estan perdudes” (Juli Palou)

5.1. Metodologies actives. Projectes d’èxit: TIL, TILC, ABP, transllenguatge, treball per àmbits, projectes interdisciplinaris, aprenentatge-servei, aprenentatge cooperatiu, seqüències didàctiques, gamificació, geolocalització, etc.

Proposem treballar amb metodologies actives que impliquen l’alumnat al màxim i el facen protagonista: Aprenentatge Basat en Projectes (ABP), Aprenentatge Cooperatiu (AC), seqüències didàctiques (SD) que connecten amb l’experiència de l’alumnat, Aprendre a Aprendre (AA), i l’Aprenentatge Competencial (AC), amb recursos com la gamificació, geolocalització.

Una de les possibilitats que millor permeten la integració de llengües i continguts és el treball per projectes amb eines digitals (TIC) permet potenciar la creativitat, facilita l’elaboració i la difusió del producte final.

L’aprenentatge basat en projectes (ABP) és una innovació centenària, com apunta Trujillo (2017). Els seus orígens se situen als Estats Units entre finals del segle XIX i principis del XX, especialment amb la proposta de Kilpatrick de l’any 1918. Aquesta proposta educativa té un gran potencial, sobretot en les àrees lingüístiques, en què hi ha «una major proporció d’elements curriculars flexibles, d’aplicació social i relacionats amb el saber fer» (Trujillo, 2017: 46).

Els objectius fonamentals que es pretenen promoure amb aquesta metodologia són: atendre la diversitat d’interessos i destreses de l’alumnat, integrar les quatre habilitats lingüístiques, propiciar les relacions interdisciplinàries i introduir l’avaluació formativa. S’hi prioritza la importància del treball cooperatiu i el reforç de l’aprenentatge individual, a més del començament en l’activitat d’investigació, l’anàlisi i interiorització de la informació, i la relació amb el context social en què té lloc l’aprenentatge (segons Camps i Vilà, 1994).

L’enfocament metodològic consisteix en el desenvolupament d’un projecte de treball connectat amb alguna àrea del currículum amb la incorporació de les TIC. Es presenten un conjunt d’activitats organitzades i seqüenciades en funció d’un resultat o producte determinat (una ruta lingüística, un muntatge audiovisual…). Trobem molts avantatges, per exemple: integrar el treball de diferents tipus de textos; donar protagonisme a les activitats de lectura, escriptura i oralitat; i afavorir l’assimilació d’aprenentatges. A diferència del model d’ensenyament tradicional, la inserció dels continguts en un projecte, que segueix un itinerari fins que s’arriba a un producte final, dota de consistència i sentit l’aprenentatge.

Trujillo (2017) assenyala que l’ABP és una estratègia innovadora avaluable i observable. Proporciona, a través de l’ús de portafolis, rúbriques i diaris d’aprenentatge, moltes dades que permeten saber si s’ha produït l’aprenentatge, si han aparegut dificultats, així com avaluar per a qualificar i per a regular l’aprenentatge.

Per treballar els projectes dissenyarem les activitats seguint un model de seqüència didàctica (SD) que siga obert, i no un esquema inamovible, en què es prenga en consideració l’aspecte comunicatiu i s’atenga a la interacció entre professorat i alumnat.

D’acord amb Camps (1996), un projecte de llengua es compon de tres fases: preparació, realització i avaluació. A la primera, es planteja la finalitat i els objectius del projecte; a la segona, s’organitzen les activitats de planificació dels continguts, textualització i revisió adaptades al procés d’aprenentatge de l’alumnat, i, a la tercera, s’avalua el projecte final juntament amb la valoració del procés seguit pels estudiants durant la realització del projecte. Cada projecte determinarà quin tipus d’activitats són les més adequades.

Hem de destacar la importància de tres elements caracteritzadors que considerem fonamentals per a desenvolupar de forma eficaç didàcticament la SD i que prenem del que proposen Milian i Camps (2006): l’activitat, el fer i el producte resultant de la SD; el procés per estimular el raonament metalingüístic, i la interacció entre professorat i alumnat.

PLANIFICACIÓ

La seqüència d’activitats plantejada segueix la proposta presentada per Kilpatrick el 1918 quan va definir el mètode de projectes com un pla de treball amb l’objectiu de realitzar alguna cosa que desperte el propi interés. Les fases de treball serien: plantejament o proposta, planificació o elaboració, i presentació i avaluació.

Quadre 1. Esquema de les fases dels projectes de treball (elaboració pròpia)

1a fase: Proposta. Es constituïxen els grups de treball de forma heterogènia, de manera que es potencie el treball cooperatiu; es decideixen els projectes a partir de models que es proposen amb els recursos TIC que s’hi poden emprar.

2a fase: Planificació. Es fa un seguiment de l’organització del projecte i s’assessora els grups sobre l’ús de les TIC i l’aplicació didàctica que se’n pot fer.

Quadre 2. Fitxa de la planificació d’un projecte de treball (elaboració pròpia)

3a fase: Elaboració. Recopilació d’informació, realització de les activitats de la SD i elaboració del producte final.

4a fase. Presentació i avaluació. Els grups exposen els projectes realitzats, mentre la resta de la classe valora el treball dels companys i les companyes, anotant-ne els aspectes més interessants i preguntant els dubtes que els han sorgit o proposant qüestions relacionades amb els temes plantejats. Després, es realitza una posada en comú i es comenten les dificultats i els avantatges trobats en l’elaboració dels diferents projectes. A més a més, cada alumne ha de respondre individualment un qüestionari d’avaluació en què se li demana que valore l’originalitat, l’estructuració, i l’interés dels projectes presentats, així com l’exposició duta a terme per cada grup.

També s’ha de fer difusió del projecte mitjançant les xarxes socials (YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, etc.), o bé amb exposicions al centre educatiu o a la localitat, o amb la participació en concursos relacionats amb el producte elaborat en el projecte.

Els productes han de tenir una intenció didàctica i de comunicació, tal com afirma Barroso (2013), que estableix una sèrie de principis generals on es deixa clar que l’aprenentatge no depén del mitjà sinó de les estratègies i tècniques didàctiques que apliquem en el seu ús. Es tracta d’integrar les TIC en el currículum aprofitant el seu gran potencial com a mitjans que impulsen els processos de comunicació, així com per a la innovació i per a la millora de les pràctiques educatives.

COMPETÈNCIA INFORMACIONAL A L’AULA

El terme competència informacional neix de la necessitat de trobar un terme específic per a denominar l’ensenyament i aprenentatge de conceptes, habilitats i actituds relacionats amb l’ús de la informació tot integrant diferents llenguatges i suports comunicatius i implicant tots els processos tant de cerca, tractament com d’ús de la informació que tenen lloc perquè es produeixi la transformació de la informació en coneixement. Si bé el terme és recent, els processos i les capacitats implicades han existit sempre però vinculats fina ara a la cultura impresa.

Es posa l’accent en els processos cognitius i lingüístics que s’activen en la gestió de la informació i en la creació de coneixement. Es tracta d’aprendre a pensar, decidir i compartir. Consta de 3 grans capacitats que es mostren desplegades en la següent imatge:

Quadre 3. Gràfic que representa les 3 capacitats de la competència informacional, que es desenvolupen en 3 habilitats i en 3 destreses bàsiques

Quadre 4. Esquema de la competència informacional en relació amb altres competències

No es tracta de deixar de transmetre continguts sinó d’ensenyar a pensar amb, a partir de, i a través dels continguts.

PROCÉS DE RECERCA DINS D’UNA SD

1. Inici amb un punt de partida motor. Es tracta de plantejar una situació-problema a resoldre que desencadeni una pregunta principal.

2. Activació de coneixements previs. L’alumnat ha de poder expressar i comunicar als altres el que pensa sobre la qüestió plantejada.

3. Emissió d’una hipòtesi. Cal facilitar la formulació de les idees que hi ha al voltant de la situació-problema i en conseqüència activar la cerca de possibles respostes.

4. Planificació de la investigació. Permet organitzar un pla de treball i determinar una temporalització per les tasques que s’han de realitzar

5. Realització de les activitats planificades. Són les accions que posaran a l’alumnat en contacte amb la informació i suposarà el procés concret de localització i recuperació de la informació.

6. Interpretació dels resultats i l’obtenció de conclusions. Són accions imprescindibles per a validar o rebutjar la hipòtesi plantejada i esdevenen claus per a poder generar coneixement personal.

7. Expressió i comunicació dels resultats de la investigació. El procés de recerca ha de finalitzar amb l’elaboració d’un producte concret que sigui rellevant, que tingui la finalitat de recopilar i comunicar les conclusions extretes després de la cerca informativa.

8. Reflexió sobre el que s’aprèn i el procés seguit. El tancament real de l’activitat d’aprenentatge requereix un procés metacognitiu que necessàriament el mestre ha de provocar.

Abans de guiar el seu alumnat, el docent ha de tenir definits els diferents aspectes que determinen l’abast d’una necessitat informativa. Principalment són dos:

-

la qualitat del contingut objecte de la cerca (genèric o especialitzat)

-

la quantitat d’informació que es necessita (poca, molta, mitjana). Això es concreta especificant un nombre mínim o màxim de documents a localitzar.

Extret de la web Competència informacional a l’aula.

PROPOSTES PER AL TIL (Tractament Integrat de Llengües)

L’enfocament lingüístic integrat constitueix un principi bàsic en l’ensenyament per aconseguir/construir una societat multilingüe (Apráiz et al., 2012; Ibarluzea et al., 2021), que permet elaborar una única programació de les diverses llengües amb objectius, metodologies i criteris d’avaluació comuns, i amb continguts d’aprenentatge repartits, però encara no s’han desenvolupat gairebé models d’integració de llengües (Dolz i Idiazabal, 2013).

Alguns autors suggereixen nocions com translanguaging (García, 2009; Vallejo i Dooly, 2020) i multiliteracies (García i Kleifgen, 2020) per destacar que la competència comunicativa en parlants multilingües és dinàmica i heterogènia. Cenoz i Gorter (2017) defensen un translanguaging sustainable en un context d’ús de llengües minoritàries regionals, en el marc d’un pedagogical translanguaging (Cenoz i Gorter, 2019, 2020).

Diverses investigacions demostren que la incorporació de les llengües familiars (LF) a l’aula repercuteix en una millora de la integració de l’alumnat d’origen immigrant i en un augment de la valoració de les pròpies identitats (Cummins, 2001; Stille i Cummins, 2013), així com en un correcte desenvolupament de la competència multilingüe i millora dels resultats en l’aprenentatge (Ball, 2010, i Benson, 2009, citats en Portolés, 2020).

El Consell d’Europa recomana valorar i utilitzar la diversitat lingüística, incloent-hi les llengües que no s’ensenyen a l’escola com a recurs d’aprenentatge, implicant-hi les famílies en l’ensenyament d’idiomes (Consell d’Europa, 2019). De fet, en la promoció de l’educació multilingüe en els actuals sistemes educatius europeus, d’acord amb Portolés (2020), hi ha una tendència dominant sobre la inclusió, manteniment i foment de les llengües minoritàries i familiars. En aquest sentit, Portolés (2020) aposta per un “sistema educatiu on totes les llengües de l’alumnat, independentment de si es tracta de llengües heretades, locals o globals, siguen conegudes, reconegudes i valorades com a vehicles d’aprenentatge” (p. 139).

Torralba i Marzà (2022) demostren que els textos identitaris són una eina idònia per treballar els diferents repertoris lingüístics presents a les aules multilingües i apunten la necessitat d’un treball planificat amb llengües familiars durant tota l’escolarització que incloga un rol definit per a la participació de les famílies. Entenem per repertori lingüístic, seguint Palou (2011: 19), el conjunt de llengües diferents o conjunt de varietats lingüístiques, aprés en circumstàncies específiques i que es pot usar en diferents situacions.

Diverses investigacions demostren que la incorporació de les llengües familiars a l’aula repercuteix en una millora de la integració de l’alumnat d’origen immigrat i en un augment de la valoració de les pròpies identitats (Cummins, 2001; Cummins i Stille, 2013). Però els beneficis no són únicament identitaris. Als EUA, Thomas i Collier (2002) observen que el major predictor en el nivell de llengua anglesa de l’alumnat al·lòglot és el grau d’escolarització formal en la llengua pròpia. De forma similar, al nostre context, Oller i Vila (2011) indiquen que l’alumnat estranger en entorns catalanitzats i que usa la llengua pròpia en el context familiar amb finalitats acadèmiques, és a dir, per a llegir i no només per a conversa, obté bons resultats en català i castellà escrits, mentre que aquells que tan sols la utilitzen per a regular els intercanvis familiars, però no en fan un ús acadèmic, obtenen pitjors resultats en aquestes àrees. (Torralba, Marzà, 2022)

Per a ser competent des d’un punt de vista plurilingüe resulta fonamental saber llengües i saber gestionar-les. La competència plurilingüe i intercultural no és una superposició, ni una suma de competències monolingües (Palou i Fons, 2019a, 2019b). Aquests autors també afirmen que hi ha tres conceptes clau en aquesta competència: acollir, crear vincles i contrastar per aprendre. En aquest sentit, Palou (2011) considera que el professorat té dos reptes especials:

“El primer: escoltar les veus dels alumnes. El segon: donar sentit a l’experiència d’aprendre llengües. Per fer front a aquests dos reptes cal crear contextos en els quals es promogui la reflexió sobre el repertori lingüístic. Aquesta reflexió metalingüística i metacultural ha d’ajudar, sens dubte, a prendre consciència del potencial que sempre comporta la diversitat lingüística. “(Palou, 2011, p. 26)

Per tal de crear bones condicions d’aprenentatge, Dolz et al. (2009) consideren que la didàctica de la llengua necessita dispositius (seqüències didàctiques) i eines de tipus diferent que li permeten treballar l’ensenyament-aprenentatge de nocions i capacitats aplicades a continguts particulars.

Informació extreta de Martí Climent, A. (2022). Projecte docent. Desenvolupament d’habilitats comunicatives en contextos multilingües. UV.

Quadre 5: Esquema de la seqüència didàctica (Dolz i Schneuwly, 2006)

Més informació en Dolz, J. i Schneuwly, B. (2006). Per un ensenyament de l’oral. Iniciació als gèneres formals a l’escola. València/Barcelona: Institut Interuniversitari de Filologia Valenciana i Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

PROPOSTES PER AL TILC (Tractament Integrat de Llengües i de Continguts)

El TILC es defineix com «el tractament dels continguts d’una o més disciplines no lingüístiques —ciències, història, matemàtiques, educació artística…— conjuntament amb els recursos lingüístics adequats per a aprendre’ls d’una o més llengües» (Pascual, 2008)

Aquest tractament comporta un tipus d’organització curricular interdisciplinària, que pot incloure 2 o 3 matèries, coordinació (connexions possibles en el currículum i en la metodologia), flexibilitat (es pot partir d’un tema per a ser enfocat des de perspectives diferents per a completar-lo o enriquir-lo) i codocència (més d’un professor a classe)

Cal, per tant, considerar la transferència lingüística i la particularitat lingüística de cada llengua a l’hora de programar, així com treballar diferents gèneres textuals.

Es plantegen dos objectius alhora: ensenyar els continguts acadèmics de les diferents disciplines acadèmiques i proporcionar simultàniament competències en la llengua o llengües amb què aquests continguts són construïts.

En l’ensenyament-aprenentatge del valencià i el castellà com a L1, almenys una part dels continguts de la competència comunicativa, la que anomenem llenguatge acadèmic, es treballa millor integrada en les àrees no lingüístiques (ANL) que en el tractament com a àrea de les diferents llengües.

En el TILC s’han de privilegiar enfocaments interdisciplinaris i globalitzats que promoguen la construcció col·laborativa de coneixements mitjançant la recerca documental, la investigació directa, la reflexió i la producció.

Des d’aquests plantejaments podem agrupar l’alumnat en gran grup, en equips de treball, en treball per parelles o bé fan un treball individual. A més, cal organitzar estratègicament cada una d’aquestes modalitats d’agrupament per garantir, el suport necessari per a la consecució de la tasca, el treball col·laboratiu dels alumnes i les alumnes, i l’accés als recursos interns individuals.

En aquest aprenentatge en bastida, hi ha una redistribució de la responsabilitat en l’acompliment de la tasca, que passa progressivament del professor a l’alumne. Aquesta participació és especialment visible en el treball per projectes amb materials i recursos:

-

Formats diversos en modalitats multimèdia

-

Procedents de fonts diverses amb múltiples perspectives, visions complementàries i punts de vista oposats. Adequats a les possibilitats de comprensió de l’alumnat (de vegades caldrà fer-ne una adaptació).

-

De fonts externes o creats pels alumnes i les alumnes.

L’enfocament didàctic suposa un treball més experimental; coneixements construïts des de diverses perspectives; domini en profunditat del llenguatge per a l’observació, l’anàlisi, l’experimentació, el raonament deductiu, i la construcció i la comunicació de coneixements.

També és fonamental la utilització de les TIC com un instrument més de treball, considerar l’entorn com el camp d’estudi idoni per a entendre’l i el medi vital sobre el qual cal actuar per millorar-lo.

COMPONENTS ESSENCIALS DEL TILC PER A L’ELABORACIÓ D’UNA UNITAT DIDÀCTICA

En el model que presenta Pascual (2008) es considera que el desenvolupament lingüístic, acadèmic (continguts de les àrees no lingüístiques) i cognitiu; l’atenció a l’ús, i els elements culturals i el context sociocultural en són els components essencials. A més a més, aquests components són complexos i estan absolutament interconnectats.

Figura 2: Model per a l’aplicació del TILC (Pascual, 2008)

ESTRUCTURA I ORGANITZACIÓ D’UNA UNITAT TEMÀTICA TILC

A. Objectius, continguts i criteris d’avaluació

| Objectius | Acadèmics, lingüístics, cognitius i culturals (independents o integrats) |

| Continguts | Acadèmics (fets i conceptes, procediments i actituds, de les àrees no lingüístiques).

Lingüístics:

Cognitius:

Culturals |

| Criteris d’avaluació | Acadèmics, lingüístics, cognitius i culturals (independents o integrats). |

B. Procés d’ensenyament/aprenentatge

| Abans |

|

| Durant |

|

| Després | Activitats que faciliten als alumnes i les alumnes:

|

C. Materials curriculars i recursos

| Amb formats diversos en diferents multilectoescriptures.

Procedents de fonts diverses amb múltiples perspectives, visions complementàries i punts de vista oposats. Adequats a les possibilitats de comprensió dels infants (de vegades caldrà fer-ne una adaptació). De fonts externes o creats pels alumnes i les alumnes. |

D. Agrupaments

Agrupaments flexibles, que permeten:

|

E. Participació de les famílies i l’entorn social

| Participen… | Com a informadors, des de casa.

Com a coneixedors de la cultura del grup, participant en l’aula. Com a experts en un tema, participant en l’aula. |

F. Avaluació

| Característiques | Tindrà en compte tots els factors: continguts, llengua, cognició, cultura.

Haurà de ser tan contextualitzada com l’ensenyament-aprenentatge. Es contrastarà amb l’opinió dels pares i les mares. |

| Tipus | Inicial: explicitació de les competències i els coneixements previs.

Contínua: control de l’ensenyament/aprenentatge al llarg de la unitat. Final: dels aprenentatges i del procés (dels materials, de l’actuació del mestre o la mestra, i del procés d’ensenyament–aprenentatge). |

Quadre 5. Model d’una unitat temàtica, segons V. Pascual (2008), Caplletra 45

La incorporació dels continguts lingüístics a una unitat hauran d’estar:

- Integrats en les activitats sobre continguts disciplinaris

- Desenvolupats mitjançant la interacció a classe

Els coneixements es queden descontextualitzats i buits de significat quan queden circumscrits als límits de l’aula. Perquè adquirisquen tota la seua potencialitat educativa i transformadora han de ser generats/aplicats en relació dialèctica amb l’entorn des de la percepció que tenen els aprenents de les incògnites i els problemes del seu món interior, i de la realitat local o global que els envolta. Des d’aquesta percepció es fan preguntes i elaboren respostes, analitzen problemes i aporten solucions. I és amb aquestes respostes i solucions com expressen la seua visió del món i la identitat pròpia. A més d’explicar amb arguments científics la realitat física, natural i social en què viuen, permeten als alumnes i les alumnes analitzar-la críticament i els engresquen a posar el seu gra d’arena en el procés de canviar-la i millorar-la.

Aquest coneixement nou, investigat, processat i elaborat des d’una perspectiva crítica i amb voluntat d’acció social, pot constituir fàcilment l’activitat o producte final d’una unitat i prendre la forma de:

|

Documents orals |

Exposició oral, debat, representació teatral… |

|

Documents escrits |

Informe escrit, mural, àlbum, informe, reportatge, fullet informatiu, pamflet, manual d’instruccions, cartell… |

Quadre 6. Activitats finals de síntesi/generació de coneixement nou

En el TILC, doncs, trobem una pedagogia transformadora i crítica que permet la generació de coneixement nou i l’actuació sobre la realitat social que ha de defugir l’ús d’enfocaments didàctics que afavoreixen la transmissió unidireccional de coneixements fragmentats i ja elaborats des de les diferents disciplines acadèmiques i ha de privilegiar enfocaments interdisciplinaris i globalitzats que promoguen la construcció col·laborativa de coneixements mitjançant la recerca documental, la investigació directa, la reflexió i la producció.

Informació extreta de Pascual Granell, V. (2008). Components i organització d’una unitat amb un tractament integrat de llengua i continguts en una L2. En: Caplletra: Revista Internacional de Filologia, No. 45: 121

PROPOSTES DE PROJECTES TIL/TILC

La proposta «Llengües de casa, llengües d’escola» ha estat generada per un equip col·laboratiu entre investigadores universitàries i mestres d’escola per a elaborar un projecte didàctic al voltant de la identitat cultural i lingüística com a marc que provoque interaccions d’aula que impliquen totes les llengües familiars (García i Sylvan, 2011). L’experiència d’incorporació de les llengües familiars s’ha organitzat al voltant dels anomenats “textos identitaris” bilingües, definits com a productes creatius de l’alumnat en un context pedagògic orquestrat pel docent, en els quals els autors aboquen les seues identitats de forma escrita, parlada, visual, musical o dramàtica, en aquest cas, en la llengua o les llengües de casa i la llengua d’escolarització (Cummins i Early, 2011; Cummins et al, 2005).

L’estudi sobre «Llengües de casa, llengües d’escola», dirigit per Torralba, G. i Marzà, A. (2017), demostra com la incorporació de les llengües familiars a l’aula repercuteix en una millora de la integració de l’alumnat immigrat i en un augment de la valoració de les pròpies identitats.

La investigació ha comptat amb la col·laboració de tres escoles de la província de Castelló i en ella, l’alumnat ha creat els anomenats «textos identitaris» bilingües, és a dir textos escrits o parlats en la llengua materna i la llengua d’escolarització on reflexionen sobre la seua identitat. En aquest cas els infants, sovint ajudats per les famílies, han tractat temes que van des de viatges fins gastronomia o política, i ho han fet en valencià i les llengües que parlen a casa, entre les quals s’inclouen l’àrab, el xinés o el romanès.

Els resultats demostren, d’una banda, que és possible incloure a l’aula llengües desconegudes per la majoria de l’alumnat i dels docents; i per una altra, que projectes d’aquesta mena ajuden a desenvolupar la integració i l’autoestima de l’alumnat immigrant, així com la perspectiva intercultural d’aquell d’origen espanyol. No obstant això, en l’entorn s’ha observat que els mestres i les mestres troben a faltar una major formació en integració de llengües que els ajude a superar les pors i les dificultats a treballar a l’aula amb llengües que no coneixen, d’ací la importància d’aquest tipus de projectes.

Podeu veure una mostra del projecte en el vídeo «Llengües de casa, llengües d’escola»

Informació extreta de Torralba, G. i Marzà, A. (2017). «Llengües de casa, llengües d’escola», de Gloria Torralba i Anna Marzà. Comunicació presentada en el VIII Seminari Internacional “L’aula com a àmbit d’investigació sobre l’ensenyament i l’aprenentatge de la llengua”. UVic-UCC. https://mon.uvic.cat/aula-investigacio-llengua/files/2015/12/TorralbaMarza.pdf

El PROGRAMA EUROMANIA neix d’un projecte europeu amb l’objectiu de desvetllar interessos plurilingües i avançar cap a una competència lectora plurilingüe en set llengües romàniques: català, castellà, francès, occità, romanès, italià i portuguès.

El material per treballar el projecte Euromania és el resultat de tres anys de treball d’un grup d’experts. Consta de 20 dossiers per a l’aprenentatge multilingüe de les àrees de matemàtiques, història, ciències i tecnologia i va adreçat a l’alumnat amb edats compreses entre els 8 i els 12 anys.

L’originalitat del mètode Euromania resideix en la seva dualitat. Es treballen les matèries amb l’ajut de suports redactats en les llengües romàniques. Al mateix temps, es construeixen les competències d’intercomprensió a través del suport de les àrees.

El document que exposa el modelatge d’un mòdul d’Euromania, concretament la unitat 20 “Não te percas” de J. Ortiz (UPF) pot servir d’exemple per a la resta de mòduls i així poder observar els elements lingüístics que s’han de tenir en compte a l’hora de preparar les classes. També s’adjunten materials complementaris.

- Module 1 : Le mystère du “mormoloc”

- Elements bàsics de pronunciació de les llengües romàniques

- Estratègies per treballar la comprensió

Altres materials i recursos que es poden consultar:

Corpus de contes per treballar la intercomprensió a l’aula.

Vídeos d’un minut de durada sobre temes de ciències en català, francès i anglès, que també inclouen la transcripció del text.

Manual Euromania, versió en català

Material per treballar el projecte Euromania elaborat per un grup d’experts. Consta de 20 dossiers per a l’aprenentatge multilingüe de les àrees de matemàtiques, història, ciències i tecnologia i va adreçat a l’alumnat amb edats compreses entre els 8 i els 12 anys.

Lloc web que presenta un nou projecte sobre les llengües romàniques minoritzades. Es pot trobar informació sobre llur localització geogràfica, llurs dialectes, llur situació actual, una petita gramàtica de cada llengua, textos literaris, etc.

Neix de la voluntat d’incorporar a les aules de secundària l’estudi conjunt de totes les llengües romàniques, i se centra en el treball de la competència lectora.

Curs d’aprenentatge simultani de quatre llengües romàniques (es pot triar entre francès, italià, català, espanyol i portuguès). Es tracta de fer-ho en un període de temps força curt, entre trenta i quaranta hores, desenvolupant estratègies de lectura que ens permetran un ús àgil de les passarel·les lingüístiques que ens ofereixen les llengües romàniques.

Accés a eines de traducció automàtica entre diverses llengües: