Assessment in the classroom

7.4. EVALUATION IN THE CLASSROOM

Progress must be made towards a humanistic and emancipatory education which, far from producing servile and functional individuals, is oriented towards the development of critical citizenship, social participation and awareness of oneself and one’s own life.

The current moment requires being able to rethink what opportunities, what accompaniments, what experiences and what knowledge formal education can offer that are beneficial to love learning and never stop doing so, consciously, ever; to be able to do it inside and outside the classrooms of the educational centers and, in addition, to be able to do it from the diversity of interests and wills of each person.

From this proposal, tensions and apparent contradictions can be raised:

-

Does the school have to make visible the learning that takes place in other environments and institutions? Does the school have to mediate? Should the school keep them in mind and empower them?

-

How do you learn alone and what does it mean to learn in community? Does the socio-constructivist model and the idea of personalization learning and of individual learning contradict itself? How can we find learning environments where these personal itineraries can be shared and built in interaction with others?

-

Is there a break between face-to-face learning and distance and online learning? How are digital technologies and learning related? Are we able to think critically and intervene effectively?

More information at UAB: Itinerari Aprendre a dins i aprendre a fora de l’escola: ruptura o contínuum? Institut de Ciències de l’Educació

Evaluate to learn, evaluate to motivate

In recent years, despite the implementation of internal evaluation and external evaluation systems, despite the impact of PISA tests and despite the growing number of evaluation actions of all kinds, most of the training activities aimed at teachers have been related to the analysis of results and how to improve them. The learning of techniques that allow teachers to observe and identify what students learn in relation to learning objectives reliably, and the training in the development of assessment tools adapted to the needs of each context integrated at the same time in the teaching and learning process has been maintained in the background. It is necessary for teachers to approach the world of rigorous, valid and reliable assessment, taking advantage of the debate to really turn the classroom into a space where teaching, learning and evaluation, coexist harmoniously with the main objective of facilitating and improving language learning.

Extracted from Figueras, N. (2011). Avaluar per aprendre, avaluar per motivar. La mirada experta: ensenyar i aprendre llengües, Col·lecció Innovació i Formació (1), 27-43.

The key to it all: good feedback

From a traditional perspective of formative assessment, the responsibility for regulation, that is, to provide feedback to help learners identify and overcome the difficulties that arise throughout the learning process, is essentially the teacher’s, who is the one who recognizes the mistakes of the students and decides which are the most appropriate strategies to progress forward. On the other hand, evaluation with a formative purpose implies much more involvement of students in their self-regulation, based on self-evaluation and co-evaluation processes.

The work of teachers should focus more on promoting systems that favour evaluation, understood as peer regulation, and self-assessment, understood as a reflection on what needs to be improved and how, than on what we call “correcting” student productions. It goes without saying that the strategies to be applied must be creative, avoiding routines, so that students perceive them as useful and rewarding. Good feedback cannot focus on identifying errors but, firstly, on recognizing what is already done well enough or believed to be done well enough (and, therefore, should not be forgotten) and, secondly, on helping to understand the appropriateness of the applied logic in carrying out the activity, because it is the one that needs to be reviewed, and to suggest possible ways to progress.

As we have seen, in order for students to be able to self-evaluate (and co-evaluate) they must take ownership of the learning objectives, and represent how to anticipate and plan actions to apply the broad types of knowledge in competency activities and the criteria for evaluating their quality. This does not mean that these three items should be evaluated/regulated always and separately. If learners internalize them, since they are all interrelated, it is often not necessary to evaluate them separately, since, for example, an orientation base makes it possible to check whether the person learning represents the objectives of what they are doing and, at the same time, the evaluation criteria. And vice versa, while talking about the evaluation criteria, you can recognize what is important to plan how to solve a type of task and its objectives.

Undoubtedly, evaluating/regulating all these aspects related to the learning activity promotes that a learning process has a much greater probability of success and, therefore, that it increases the self-esteem of learners. Instead of spending a lot of time going over what has not been learned well enough, it is much more practical to use it in prevention. We already know that prevention is better than cure.Therefore, the three actions that we have traditionally differentiated at school cannot be separated: teaching, learning and evaluating, since without formative evaluation there is no learning and without encouraging students to face their difficulties and overcome the obstacles they encounter, we cannot talk about useful teaching. Thus, it must be an activity integrated into the learning process, so it is necessary to promote feedback from the students themselves based on tools that, with the help of teachers, they must use with meaning and not mechanically.

The evaluation seen as an activity to check what has been learned

There is no doubt that evaluation also aims to know what the learning outcomes have been, both to check whether the objectives have been achieved and to identify what is still to be learned, and to prove the results. In addition, the information obtained will be useful to evaluate the quality of the applied teaching process and identify the aspects to be improved when it is put back into practice. The evaluation of competences involves recognizing whether one is able to mobilize the different types of knowledge, in an interrelated way, to carry out an action (that is, in the resolution of open, real, complex and productive problems). It makes no sense to evaluate knowledge on the one hand and competences on the other, nor does it make sense to consider that a student has achieved a satisfactory competence without having the knowledge linked to it. This does not mean that from an evaluation task it is not possible to identify the achievement of each of the knowledge that is part of the competence, but it is necessary to be aware that if they are learnt in isolation and do not know how to integrate them into the action, it cannot be concluded that it is competent or that the knowledge has been acquired. Therefore, the evaluation carried out at the end of the learning around a specific topic must be of a competency type and a demonstration of progress in specific knowledge of each competence in each of the areas of the area or subject must be identified.

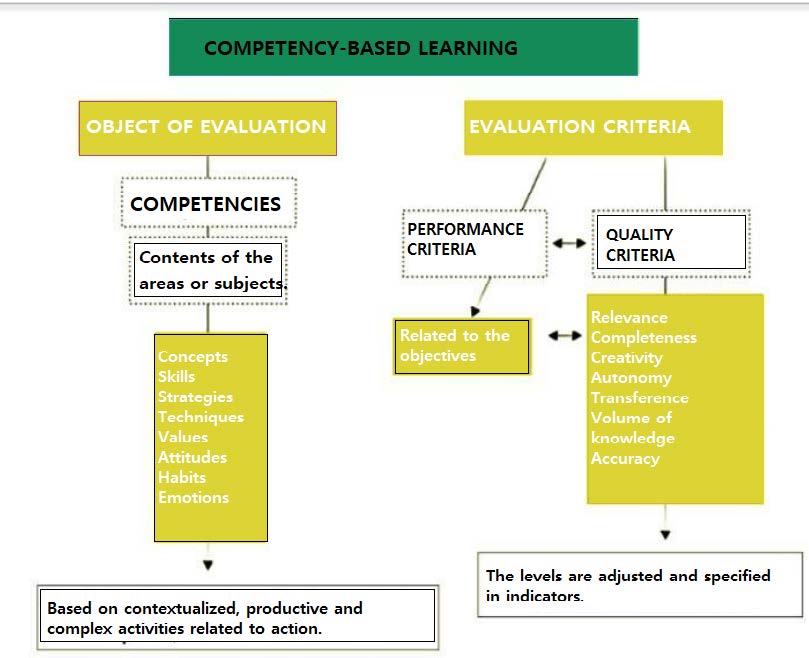

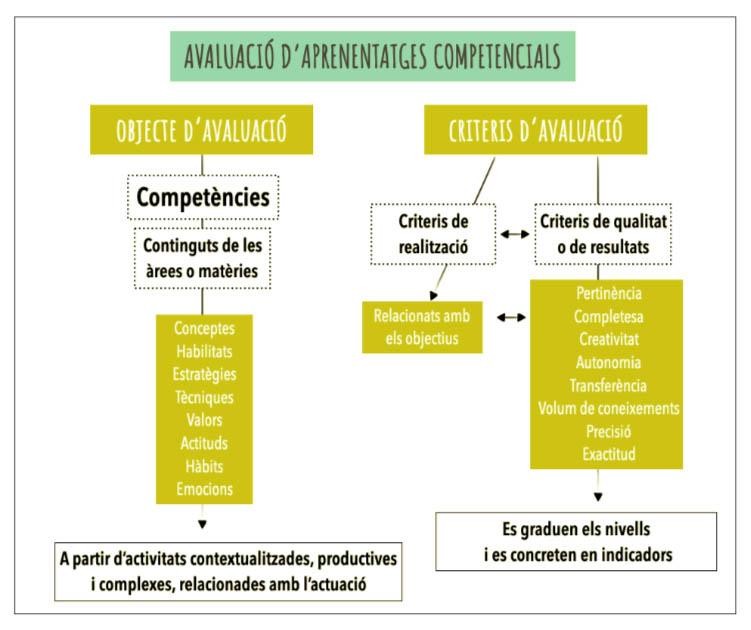

In any evaluation, it is necessary to take into account the targets to be evaluated (knowledge of different types and their interrelation in competences) and the criteria for deciding on the quality of learning, which must be consistent with the objectives, and also what is the starting point, in order to recognize how it has been improved in the achievement of competence. Learners are diverse at the beginning of a learning process and also at the end, but all must have improved.

Table 9: Objects and criteria for evaluation according to competence objectives (Sanmartí, 2020)

Evaluating is much more than “grading”. We must be aware that evaluation conditions everything that constitutes the school activity: what students want to learn (objectives), how to sequence learning over the years so that there is progress and the new ones are built on the previous ones, how the classroom can be organized so that peer learning can become a reality, how teachers can be organized so that the objectives and evaluation criteria are shared, what values are to be promoted so that learners can understand them from experiencing them, how we can respond to the different educational needs so that everyone is enriched and progressing how the relationship with families can be considered so that we can go from informing them to sharing and collaborating, etc.

That is why it is so difficult to change assessment, because it requires systemic change. We know that the whole is not the sum of the parts and, therefore, when a school and teachers consider reviewing how they evaluate, they need to rethink their entire way of promoting learning, while recognizing that evaluating is learning.

Excerpted from Sanmartí, N. (2020). Avaluar és aprendre.Government of Catalonia. Department of Education.

Inclusive evaluation

Evaluating involves collecting information, analysing it and making decisions. According to the instructions for organization and operation at the beginning of the course:

“Student assessment must be continuous and global. The purpose pursued with the evaluation is to detect the difficulties as soon as they occur, to find out the causes and to take the necessary measures so that the students can successfully continue their learning process.” (Department of Education, 2009:Instructions for the operation and organization of public schools)

The evaluation from the social point of view allows quantifying, grading to be able to classify, select, this is how the exams for Public Service are understood, the entrance exams … But evaluation from the pedagogical side, helps to regulate the teaching-learning process, to adapt individual and collective strategies, to contrast the achievement of the objectives set, to guide students, to contrast progress and when this is developed in a shared teacher to student way educates for self-regulation, necessary to continue learning.

When evaluating for grading, the focus is on assessing the results, while when evaluating for regulation it is on understanding the reasons for difficulties and mistakes.

Guidelines for inclusive assessment

-

Evaluation should encourage interest in improving; it should not exclude and punish, but offer the possibility of redoing a task better, which is why it is not yet ready.

-

Establish a coherent and conscious curriculum that provides correct, adequate and relevant information.

-

Make consensual decisions regarding learning and assessment materials that are relevant and useful.

-

Link assessment to learning and vice versa, which helps identify individual needs in learning and allows the person to ask for support without having the feeling of failure.

-

The evaluation must be detailed and improvable. It is necessary to clearly establish the evaluation criteria, students must know in advance what is expected of them, what tools they have to overcome and what types of help they can have to improve.

-

We must start from the point where the student is, that is, from their previous concepts and see their evolution.

-

Provide varied and different evaluation activities: diagrams, conceptual maps, summaries, answering specific questions, giving time to do them… using different formats and diversifying language and representation systems. It can also be a choice of the students themselves.

-

It is necessary to make use of different assessment tools: observation, scales, oral and written tests, multiple choice tests, multiple-choice questions, open-ended questions…

-

Plan together teachers and students the evaluation activities, carrying out preparatory activities in the classroom and / or sharing correction criteria.

-

Propose evaluation activities at the beginning, middle and end of the sequence of contents, as specific activities.

-

Carry out self-assessment activities, hetero-evaluation, share them among different classmates, as brainstorming in class. These procedures achieve a critical and comparative vision, and help students to grow.

-

It should help each student to enrich their learning and to know the strengths and weaknesses of the process.

-

All students do not grow according to their age. Sometimes they exceed the standards and sometimes they fall below. It is necessary to consider different types of competences, for the different activities that the student requires.

-

It is very important that the results of the evaluation are discussed with the teacher individually, in order to encourage, support, and allow the students to reflect on the results they obtain and the effort themselves.

-

Assessment should aim to offer multiple forms of evidence on students’ learning.

-

Education levels should be assessed, without imposing standardization.

7.4. AVALUACIÓ DINS L’AULA

Cal avançar cap a una educació humanística i emancipadora, la qual, lluny de produir individus servils i funcionals, s’orienti cap al desenvolupament de la ciutadania crítica, la participació social i la consciència d’un mateix i de la pròpia vida.

El moment actual demana poder repensar quines oportunitats, quins acompanyaments, quines experiències i quins coneixements pot oferir l’ensenyament formal que resultin de profit per a estimar aprendre i no deixar de fer-ho, conscientment, mai; poder fer-ho a dins i a fora de les aules dels centres educatius i, a més, poder fer-ho des de la diversitat d’interessos i voluntats de cada persona.

Des d’aquesta proposta es poden plantejar tensions i aparents contradiccions:

- L’escola ha de fer visibles els aprenentatges que es produeixen en altres entorns i institucions? Hi ha de mediar? Els ha de tenir presents i potenciar?

- Com s’aprèn sol i què significa aprendre en comunitat? Es contradiu el model socioconstructivista i la idea de personalització de l’aprenentatge i de l’aprenentatge individual? Com podem cercar entorns d’aprenentatge on aquests itineraris personals es puguin compartir i construir en la interacció amb els altres?

- Hi ha una ruptura entre l’aprenentatge presencial i l’aprenentatge a distància i en línia? Com es relacionen tecnologies digitals i aprenentatge? Som capaços de pensar-hi críticament i intervenir-hi de manera eficaç i efectiva?

Més informació en UAB: Itinerari Aprendre a dins i aprendre a fora de l’escola: ruptura o contínuum? Institut de Ciències de l’Educació

Avaluar per aprendre, avaluar per motivar

En els darrers anys, malgrat la posada en marxa de sistemes d’avaluació interna i d’avaluació externa, malgrat l’impacte de les proves PISA i malgrat el creixent nombre d’actuacions avaluatives de tot tipus, la major part de les activitats de formació dirigides al professorat han estat relacionades amb l’anàlisi de resultats i com millorar-los. L’aprenentatge de tècniques que permetin als professors observar i identificar el que aprenen els alumnes en relació amb els objectius d’aprenentatge de forma fiable, i la formació en l’elaboració d’instruments d’avaluació adaptats a les necessitats de cada context integrats alhora en el procés de docència i aprenentatge s’ha mantingut en un segon pla. Cal que els docents s’apropin al món de l’avaluació rigorosa, vàlida i fiable, aprofitant el debat competencial per convertir realment l’aula en un espai on visquin harmònicament docència, aprenentatge i avaluació, amb l’objectiu principal de facilitar i millorar els aprenentatges de llengües.

Extret de Figueras, N. (2011). Avaluar per aprendre, avaluar per motivar. La mirada experta: ensenyar i aprendre llengües, Col·lecció Innovació i Formació (1), 27-43.

La clau de tot plegat: una bona retroalimentació

Des d’una perspectiva tradicional de l’avaluació formativa, la responsabilitat de la regulació, és a dir, de fer les retroalimentacions per ajudar els aprenents a identificar i superar les dificultats que van sorgint al llarg del procés d’aprenentatge, és essencialment de l’ensenyant, que és qui reconeix els errors de l’alumnat i decideix quines són les estratègies més adequades per avançar. En canvi, l’avaluació amb una finalitat formadora comporta implicar molt més l’alumnat en la seva autoregulació, a partir de processos d’autoavaluació i de coavaluació.

La tasca del professorat s’hauria de centrar més a promoure sistemes que afavoreixin l’avaluació, entesa com a regulació entre iguals, i l’autoavaluació, entesa com a reflexió sobre què cal millorar i com, que no pas al que en diem “corregir” produccions de l’alumnat. No cal dir que les estratègies que s’han d’aplicar han de ser creatives, fugint de rutines, i que l’alumnat les percebi com a útils i gratificants. Una bona retroalimentació (feedback) no es pot centrar a identificar errors sinó, en primer lloc, a reconèixer el que ja es fa prou bé o es creu que es fa prou bé (i, per tant, no s’ha d’oblidar) i, en segon lloc, a ajudar a comprendre la idoneïtat de la lògica aplicada en la realització de l’activitat, perquè és la que cal revisar, i a suggerir possibles camins per avançar.

Com hem vist, perquè l’alumnat es pugui autoavaluar (i coavaluar) cal que s’apropiï dels objectius d’aprenentatge, i es representi com anticipar i planificar les accions per aplicar els grans tipus de coneixements en activitats competencials i els criteris per avaluar-ne la qualitat. Això no vol dir que s’hagi d’avaluar/regular aquests tres ítems sempre i de manera separada. Si els aprenents els interioritzen, atès que tots estan interrelacionats, sovint no cal avaluar-los separadament, ja que, per exemple, una base d’orientació possibilita comprovar si la persona que aprèn es representa els objectius del que fa i, al mateix temps, els criteris d’avaluació. I viceversa, tot parlant dels criteris d’avaluació, es pot reconèixer el que és important per planificar com resoldre un tipus de tasques i els seus objectius.

Sens dubte, avaluar/regular tots aquests aspectes relacionats amb l’activitat d’aprendre promou que un procés d’aprenentatge tingui moltes més probabilitats d’èxit i, per tant, que augmenti l’autoestima dels aprenents. En comptes de dedicar molt de temps a “recuperar” el que no s’ha après prou bé, és molt més rendible utilitzar-lo en la prevenció. Ja sabem que és millor prevenir que no pas curar.

Per tant, no es poden separar les tres accions que tradicionalment hem diferenciat a l’escola: ensenyar, aprendre i avaluar, ja que sense una avaluació formativa i formadora no hi ha aprenentatge i sense promoure que l’alumnat afronti les seves dificultats i superi els obstacles amb els quals es troba, no es pot parlar d’un ensenyament útil. Així doncs, ha de ser una activitat integrada en el procés d’aprenentatge, de manera que cal promoure que les retroalimentacions les facin els mateixos alumnes a partir d’eines que, amb l’ajuda dels docents, han d’utilitzar amb sentit i no mecànicament.

L’avaluació vista com a activitat per comprovar què s’ha après

No hi ha dubte que l’avaluació també té la finalitat de saber quins han estat els resultats de l’aprenentatge, tant per comprovar si s’han assolit els objectius i identificar el que encara falta per aprendre, com per acreditar-ne els resultats. A més, la informació obtinguda serà útil per avaluar la qualitat del procés d’ensenyament aplicat i identificar els aspectes a millorar quan es torna a posar en pràctica. L’avaluació de les competències comporta reconèixer si s’és capaç de mobilitzar els diferents tipus de sabers, de manera interrelacionada, per fer una acció (és a dir, en la resolució de problemes oberts, reals, complexos i productius). No té sentit avaluar coneixements d’una banda i competències de l’altra, com tampoc en té considerar que un alumne o alumna ha assolit una competència de forma satisfactòria sense tenir els coneixements que s’hi vinculen. Això no vol dir que a partir d’una tasca d’avaluació no es pugui identificar l’assoliment de cadascun dels sabers que formen part de la competència, però cal ser conscient que si es coneixen de forma aïllada i no se saben integrar en l’acció, no es pot concloure que s’és competent ni que els sabers s’hagin adquirit. Per tant, l’avaluació que es fa en finalitzar l’aprenentatge entorn d’una temàtica específica ha de ser de tipus competencial i s’han de poder identificar progressos en sabers específics de cada competència en cada un dels àmbits de l’àrea o matèria.

En tota avaluació cal tenir presents els objectes a avaluar (sabers de diferents tipus i la seva interrelació en competències) i els criteris per decidir sobre la qualitat dels aprenentatges, que han de ser coherents amb els objectius, i també quin és el punt de partida, per poder reconèixer com s’ha millorat en l’assoliment de la competència. Els aprenents són diversos a l’inici d’un procés d’aprenentatge i també al final, però tots han d’haver avançat.

Quadre 9: Objectes i criteris d’avaluació en funció d’objectius competencials (Sanmartí, 2020)

Avaluar és molt més que “posar notes”. Hem de ser conscients que l’avaluació condiciona tot allò que constitueix l’activitat escolar: què es vol que l’alumnat aprengui (objectius), com cal seqüenciar els aprenentatges al llarg dels anys de manera que hi hagi un progrés i els nous es construeixin sobre els anteriors, com es pot organitzar l’aula perquè pugui fer-se realitat l’aprenentatge entre iguals, com ens podem organitzar els docents per tal que els objectius i els criteris d’avaluació siguin compartits, quins valors es volen promoure perquè els aprenents els puguin “atrapar” a partir de vivenciar-los, com podem respondre a les diferents necessitats educatives perquè tots s’enriqueixin i progressin, com es pot plantejar la relació amb les famílies perquè es passi d’informar-les a compartir i col·laborar, etc.

Per això és tan difícil canviar l’avaluació, perquè requereix un canvi sistèmic. Sabem que el tot no és la suma de les parts i, per tant, quan un centre i els docents es plantegen revisar com avaluen, els cal repensar tota la seva manera de promoure aprenentatges, tot reconeixent que avaluar és aprendre.

Extret de Sanmartí, N. (2020). Avaluar és aprendre. Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament d’Educació.

L’avaluació inclusiva

Avaluar comporta recollir informació, analitzar-la i prendre decisions. Segons les instruccions d’organització i de funcionament d’inici de curs:

“L’avaluació de l’alumnat ha de ser contínua i global. La finalitat que es persegueix amb l’avaluació és detectar les dificultats tan bon punt es produeixin, esbrinar-ne les causes i prendre les mesures necessàries a fi que l’alumnat pugui continuar amb èxit el seu procés d’aprenentatge.” (Departament d’Educació, 2009:Instruccions de funcionament i organització dels centres públics)

L’avaluació des del punt de vista social permet quantificar, posar nota per poder classificar, seleccionar, així s’entén els concursos oposicions, les proves d’accés … Però l’avaluació des de la vessant pedagògica, ajuda a regular el procés d’ensenyament-aprenentatge, a adaptar les estratègies individuals i col·lectives, a contrastar l’assoliment dels objectius plantejats, a orientar l’alumnat, a contrastar els progressos i quan això es desenvolupa de forma compartida docent-educant educa per l’autoregulació, necessària per seguir aprenent.

Quan s’avalua per quantificar se centra en valorar els resultats, mentre que quan avaluem per regular se centra per comprendre les raons de les dificultats i les errades.

Orientacions per a una avaluació inclusiva

- L’avaluació ha de fomentar l’interès per millorar; no ha d’excloure i castigar, sinó oferir la possibilitat de refer millor, allò per la qual cosa encara no s’està preparat.

- Establir un currículum coherent i conscient, que doni una informació correcta, adequada i pertinent.

- Prendre decisions consensuades, respecte als materials d’aprenentatge i d’avaluació que siguin rellevants i útils.

- Vincular l’avaluació a l’aprenentatge i viceversa, que ajudi a identificar les necessitats individuals en formació i permeti a la persona a sol.licitar el suport sense tenir la sensació de fracàs.

- L’avaluació ha de ser detallada i que es pugui millorar. Cal establir clarament els criteris d’avaluació, l’alumnat ha de saber anticipadament què s’espera d’ell, amb quines eines compta per superar-se i quins tipus d’ajuda pot disposar per avançar.

- S’ha de partir del punt on es troba l’alumne, és a dir, dels seus conceptes previs i veure’n l’evolució.

- Proporcionar activitats d’avaluació variades i diferents: esquemes, mapes conceptuals, resums, respondre a preguntes concretes, donar temps per realitzar-les… emprant diferents formats i diversificant els sistemes de llenguatge i de representació. També hi pot ser una elecció del propi alumnat.

- És necessari fer ús de diferents instruments d’avaluació: observació, escales, proves orals i escrites, proves tipus test, preguntes amb respostes múltiples, preguntes obertes…

- Planificar conjuntament professorat i alumnat les activitats d’avaluació, realitzant activitats preparatòries a l’aula i/o compartint criteris de correcció.

- Proposar activitats d’avaluació a l’inici, a meitat i al final de la seqüència de continguts, com a activitats puntuals.

- Realitzar activitats d’autoavaluació, heteroavaluació, compartir-les entre els diferents companys, com a pluja d’idees a la classe. Aquestes maneres fan assolir una visió crítica i comparativa, i ajuden l’alumnat a desenvolupar-se.

- Ha d’ajudar a cada alumne a enriquir el seu aprenentatge i a conèixer els punts forts i febles del procés.

- Tots els alumnes no es desenvolupen d’acord amb la seva edat. A vegades excedeixen les normes i de vegades estan per sota. Cal plantejar diferents tipus de competències, per a les diferents activitats que requereixi l’alumne.

- És molt important que els resultats de l’avaluació es parlin amb el tutor/a de forma individualitzada, a fi d’animar, donar suport, i permetre la reflexió a l’alumnat dels resultats que obtenen i del propi esforç.

- L’avaluació hauria de tenir com a finalitat oferir múltiples formes d’evidència sobre l’aprenentatge dels alumnes.

- Els nivells d’educació haurien de ser avaluats, sense imposar estandardització.

Extret de DIEE – Inclusió educativa i estratègies de treball a l’aula: L’avaluació inclusiva